Tristan, with eyes wide shut.

It is unusual for an operatic production to be equally riveting at a visual and an aural level: typically one wins out, and one makes do with the lesser other. This phenomenon was taken to an extreme in the current production of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde at the Theatre de Champs Elysees in Paris, which this reviewer enjoyed best with her eyes wide shut.

From a purely musical point of view, a better performance of this opera would be hard to find: Daniele Gatti, conductor extraordinaire, coaxed tenderness and passion, foreboding and ecstasy, sensuality and world-weariness, from the Orchestre National de France, as well as from some of the key soloists. Torsten Kerl’s singing of Tristan’s role was flawless, while Rachel Nicholls’ singing of Isolde showed consistent improvement with a greater comfort in the higher registers as the opera progressed, till her climactic and compelling Mild und Leise. Among the minor parts, Michelle Breedt as Brangane and Steven Humes as King Marc, were impressive.

The visual component was, unfortunately, much more of a mixed bag. The costumes seemed to be designed to be as primitive as possible — Tristan’s costumes in particular made him look like a caveman, with what looked like rough-hewn rags cast across his shoulders. When this trend continued with other male characters like King Marc, one was forced to speculate: was this an overly literal insistence on the medieval era, the supposed origin of the legend of Tristan and Iseult? Was it to emphasise the rather primitive theme of the opera, that of men fighting over their ‘possession’ of women? These speculations were as unhelpful as they were distracting, and in any event did not explain the uniformity of the costumes of the female leads. Why for example were Isolde and Brangane dressed with the same lack of finesse, without allowing the former to stand out?

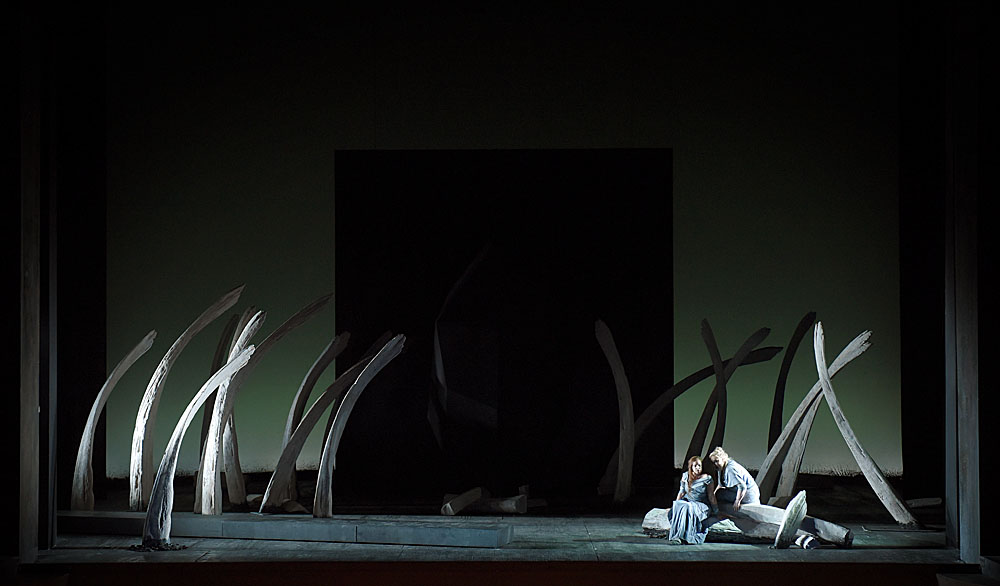

The stark austerity of the opening sets was actually rather apt, with moving wings connoting the movement of the ship; the miming of Isolde’s first encounter with Tristan accompanying the overture, and the dark brooding colours foretelling doom were intelligent touches. In the second act, the modernistic trees made to look like bent swords, had an appealing ambiguity, given the overall theme of love and death. The post-modernism of the stage sets was, however, carried too far in the last act when what looked like an open, shabby cupboard with ramshackle shelving, was meant to embody Tristan’s own (and undoubtedly noble) home. Even more annoyingly, there was (either by accident or by design) a little hole in the middle of this cupboard which let in a ray of background light; first, this was a visual distraction, and second, one kept wondering what this was meant to convey, in the event that it was intentional? In short, even apart from the needless visual distress, the studied ugliness led to a lot of avoidable speculation, which detracted from the full experience of the opera.

However, it was the stage direction that was in some sense the worst offender in this respect. The complete lack of chemistry between Tristan and Isolde was so deliberate as to be truly mystifying. A huge distance was typically maintained between the two when they were on stage: they made little eye contact in general: there was no sign of any facial emotion even when their singing of the love duets was deeply emotional; and they faced away from each other throughout their long and intense night of love in the second act, as if to avoid their forced proximity. Speculations were rife among the astonished audience, ranging from the banal — did the two performers detest each other in real life? — to the imaginative — was this an attempt by the stage directors to suggest that Tristan and Isolde were individually in love with death, rather than with the death that was a logical consequence of their doomed love for each other?

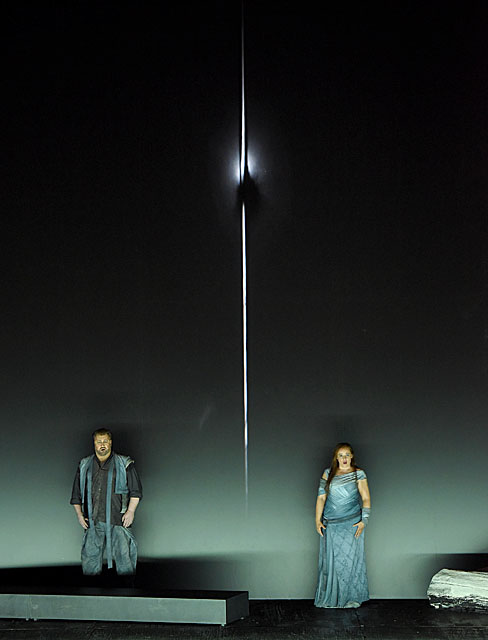

Fortunately, the opera ended with a climax that was as stunning visually as it was unforgettable aurally, with Isolde alone and resplendent against a background of light, singing an immensely moving Liebestod. As she sang ‘Do you see, friends? Do you not see?’ (‘Seht ihr’s, Freunde? Seht ihr’s nicht?’), all tensions between light and sound, love and death, sensuality and renunciation, resolved themselves into emotions that were no longer separable, that went beyond words and into wordlessness.