The Joy of Learning to Play Music, Part IV

A four-part series of reflections on the pleasures and paradoxes of learning to sing or play an instrument. For parents, musicians, and would-be musicians of all ages.

The Ultimate Holistic Practice

What is the meaning of “holistic”?

The Oxford Dictionary gives two definitions, the first related to philosophy:

“characterized by the belief that the parts of something are intimately interconnected and explicable only by reference to the whole.”

And the second related to medicine:

“characterized by the treatment of the whole person, taking into account mental and social factors, rather than just the symptoms of a disease.”

In this article I’m interested in how the holistic nature of music-making can support our general well-being.

Interest in holistic practices has increased exponentially in recent decades. Some, such as yoga, are ancient practices, demonstrating that the desire for good health is nothing new. Nevertheless, it seems clear that there has been a ramping up of interest in any method that helps us find balance in our ever-more-frenetic lives. There is particular emphasis on counter-balancing the effects of our digital existence, social media, screen and desk time, and since 2020, social isolation caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The 1982 cult-classic film “Koyaanisquatsi” is a prescient commentary on our lifestyle. A film by Godrey Reggio with music by Philip Glass, whose Hopi language title translates to “Life Out of Balance”, it is a non-narrative, abstract exploration of the relentless pace of life (even pre-internet) and the toll it takes on humans and the planet. You can watch the film online—the larger the screen, the better.

Truth be told, some scenes from “Koyaanisquatsi” seem almost quaint forty years on, so frenzied has modern life become. But the message is already there: this is not a healthy way forward.

In my way of thinking, music and all forms of art and creativity are better ways forward. These engage the higher aptitudes and satisfy the deeper needs of humans. All cultures have created outlets that speak to the need for this kind of holistic balance and nurturing: creative arts, sports, meditation techniques, martial arts, bodywork, group therapy, psychotherapy, theatre, dance, drumming, and so forth.

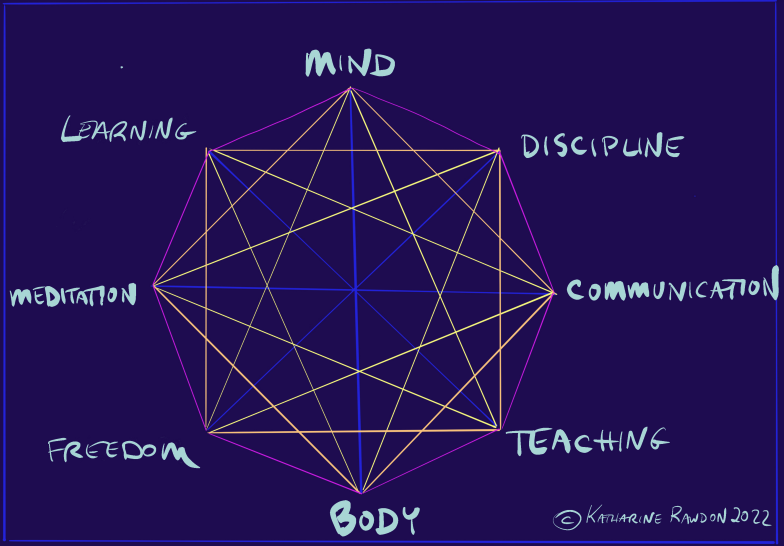

What gives music-making its remarkable value as a holistic practice is the interconnectedness of the act of playing or performing. You simply cannot separate out the parts: without the physical it is non-existent; without the mind it is incoherent; without emotion it is meaningless; without spirit it is vacuous.

It requires solitary pursuit without excluding group work, and can lead to public performance in disparate settings for disparate purposes—from the most intimate to the most public, from the cathedral to the Irish pub!

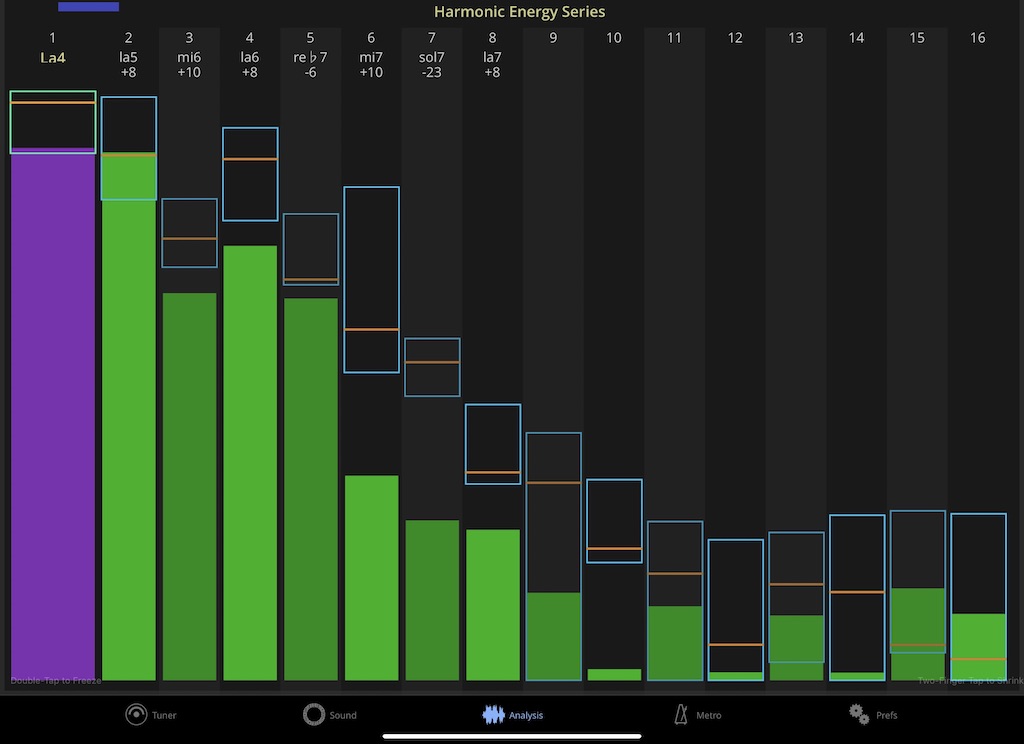

As an example, when I am playing flute, I am also—unofficially—partaking in bodywork (balancing muscular efforts in the most efficient way), breath work (controlling inhalation/exhalation), physical exercise (training for strength, precision, and endurance), emotional and psychological exploration (What is the expressive journey of this music?), mental calculation (deciphering the score), meditation (maintaining awareness), and sound therapy (feeling and hearing the vibrations produced). At the very least.

A fabulous “internet” connects all these aspects. Putting yourself in touch with these interdependent elements on a daily basis brings about a kind of balance and completeness that simply cannot be found scrolling through social media.

Music-making is an antidote to the culture of consumption. In the last forty years or so, I’ve noticed how common it has become to refer to people as “consumers”—is this really our essence? Did Descartes write “I consume, therefore I am”? Has consumer culture brought us happiness? To judge by the epidemic of depression and the mushrooming interest in finding happiness, the answer is no.

During the pandemic lockdown (I will optimistically refer to it in the past tense…), I observed a division: there were those who, cut off from the daily “rat race”, felt adrift and empty. Lacking the habit of a creative outlet, many resorted to increased social media or consumption of “content” online to occupy empty time. But there were others who, freed from hours spent commuting (and granting a situation that permitted) used that extra time for creative activities or other holistic practices. In my personal, unofficial impression, the first group had a generally negative experience of lockdown, suffering from anxiety and isolation. The second group, however, which includes the vast majority of my musician and artist friends, not only survived but thrived during lockdown.

In a nutshell, and using broad strokes, this split reveals the difference between the consumerist and the creative mindsets. While consumerism breeds conformity and feeds off insatiable desires, creativity flourishes best with limitations. Considering our intrinsic human drive for “more”, the question is whether to apply that drive to acquiring material goods, or to exploring modes of expression and fulfilling creative potential.

Music-making is an antidote to materialism: music produces nothing tangible, it is ephemeral. Like books and film and theatre it contains storytelling but in an abstract form. Music is essentially vibration, produced by the musician and experienced by the audience in proximity or via a recording.

In a Scientific American article from 2018, the researcher Tam Hunt described the General Resonance Theory of consciousness that he and Jonathan Schooler are developing, saying it “…suggests that resonance—another word for synchronized vibrations—is at the heart of not only human consciousness but of physical reality more generally.”

Hunt sums up humorously by saying that it appears that “the Hippies were right!” in their “radical intuition that it’s all about vibrations… man.” And furthermore, stating that “resonance and vibrations… are the basic mechanism for all physical interactions to occur.”

The musician, even a beginner, experiences firsthand this connection to… everything. To produce a sound is satisfying. To produce an emotionally-connected succession of musical sounds is profoundly satisfying.

To close this series of articles, I would like to quote from the moving speech given by the pianist Karl Paulnack at Boston Conservatory in 2009. Paulnack defends music as “the opposite of entertainment”, citing that in ancient Greece “music was seen as the study of relationships between invisible, internal, hidden objects. Music has a way of finding the big, invisible moving pieces inside our hearts and souls and helping us figure out the position of things inside us.”

He cites the human need to create art and music even in the most inhumane of circumstances such as the concentration camps of World War II; and points to the performance of the Brahms “Requiem” as “the first organized public expression of grief, our first communal response” to September 11th in New York City.

I have drawn a graphic showing some of the aspects involved in music-making that, working together, bring about this realignment of our hearts and souls. It emphasizes pairs of apparent opposites; each title represents a group of related skills. For example, “Discipline” stands for objectivity, rigour, or precision, while “Freedom” stands for subjectivity, spontaneity, or improvisation. Integrating these elements—our lovely paradoxes—gives music its extraordinary richness.

So delay no further. Pick up the instrument that speaks to your heart, begin to sing or simply clap, and in a spirit of playful curiosity, begin your own musical journey. As musicians, we always have at our disposal a way to integrate ourselves, connect to others, and enrich our human experience.