The Joy of Learning to Play Music, Part II

A four-part series of reflections on the pleasures and paradoxes of learning to sing or play an instrument. For parents, musicians, and would-be musicians of all ages.

We have seen that learning to sing or play an instrument involves a lot of very worthwhile work. Understanding notation, controlling the physicality of the particular instrument, and solidifying complex automatic responses in order to serve the music—all require a specific kind of work over an extended period of time. In his research, psychologist Anders Ericsson called this “deliberate practice”: focused work just a bit beyond one’s comfort zone.

At the same time, playing music needs to somehow remain fun. Without playfulness we risk becoming boring, rote performers who lose contact with the creative spark… and eventually quit. Noa Kagayama, Professor of Performance Psychology at the Juilliard School in New York writes:

“…focusing too single-mindedly on technical precision sucks a lot of the fun out of the experience, both for us and for our audience.”

How can the paradoxical need for both discipline and fun be reconciled? Which should have priority in order to progress optimally?

Terminology leaves some clues: in English we “play” an instrument; in French it is jouez, and in German spielen, both also meaning “play”. In Portuguese and Spanish it is tocar, “to touch”; in Italian suonare, “to sound” (rather precise). The Japanese (yet more precise) have different words for the specific actions that make an instrument sound, for instance, “blow”—winds, “hit”—piano or percussion, or “rub”—as in a bow across a string.

In no language yet discovered by me do we “work” an instrument!

But if you talk about learning music with your teacher, your child’s teacher or most musicians, they will stress first and foremost the consistent work (study, practice) that must be done to progress. And they are not wrong.

In my way of thinking, it is a draw, and a case of acknowledging that in this context the concepts of “work” and “play” are not opposites. Rather, the two go hand in hand, each bolstering the other.

How can we achieve this? It is a question of stepping back and examining our way of practicing.

If we adopt the logical attitude that a certain amount of work will produce a certain amount of results, while twice as much work will produce twice the results, we will be in for a surprise! With scrutiny and honest evaluation, we discover that the quality of attentiveness we have while we work is far more important than the sheer quantity of time spent. A mindset of playful curiosity can yield four times the results of “dull work”. And four times longer spent in mindless, mechanical work might produce no results at all—or even cause backsliding: the acquisition of counterproductive habits and a distaste for the entire project. BEWARE!

Think back to school days: do you recall working half-heartedly on some project for many grinding hours with a mediocre result, yet at another time, working in a happy, relaxed way on a different project, finishing in “no time” with excellent results? This is the effect of enjoying the work.

Who are the undisputed experts in this skill?

Children! For a child, “play” is their work. Their “job” is to explore and discover: what happens when I do this? And if I do that? The child is acquiring an enormous number of interrelated skills—just as a musician must.

So, does it make sense to tell a child (or ourselves) to “work on the violin every day”, and similar exhortations, as if learning music were a day job for a six-year-old? While there is real work involved, and daily practice is ideal, leaving the “w” word out of the equation is likely a better tactic.

The work can be, so to speak, wrapped up in play. This sounds childish, but a playful mindset is equally advantageous for adults—we are not so terribly different!

For example, make a game out of the (absolutely necessary) repetition of musical passages: four times correctly through a passage might count as a “win”. If you reach three and then mess up, your “score” moves either back to two (soft version) or back to zero (hard version). And so forth.

The concept of “flow” proposed by the psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihály states that there is an optimal range of difficulty within which our mental focus remains productive. This “flow” zone is where maximum learning takes place: the task must be neither too difficult nor too easy. While practicing, we can adjust the task to keep us in this zone, for instance simplifying hard passages or challenging ourselves to memorise or transpose an easy one. The priority is to remain working “in the zone” rather than to clock so many minutes of practice.

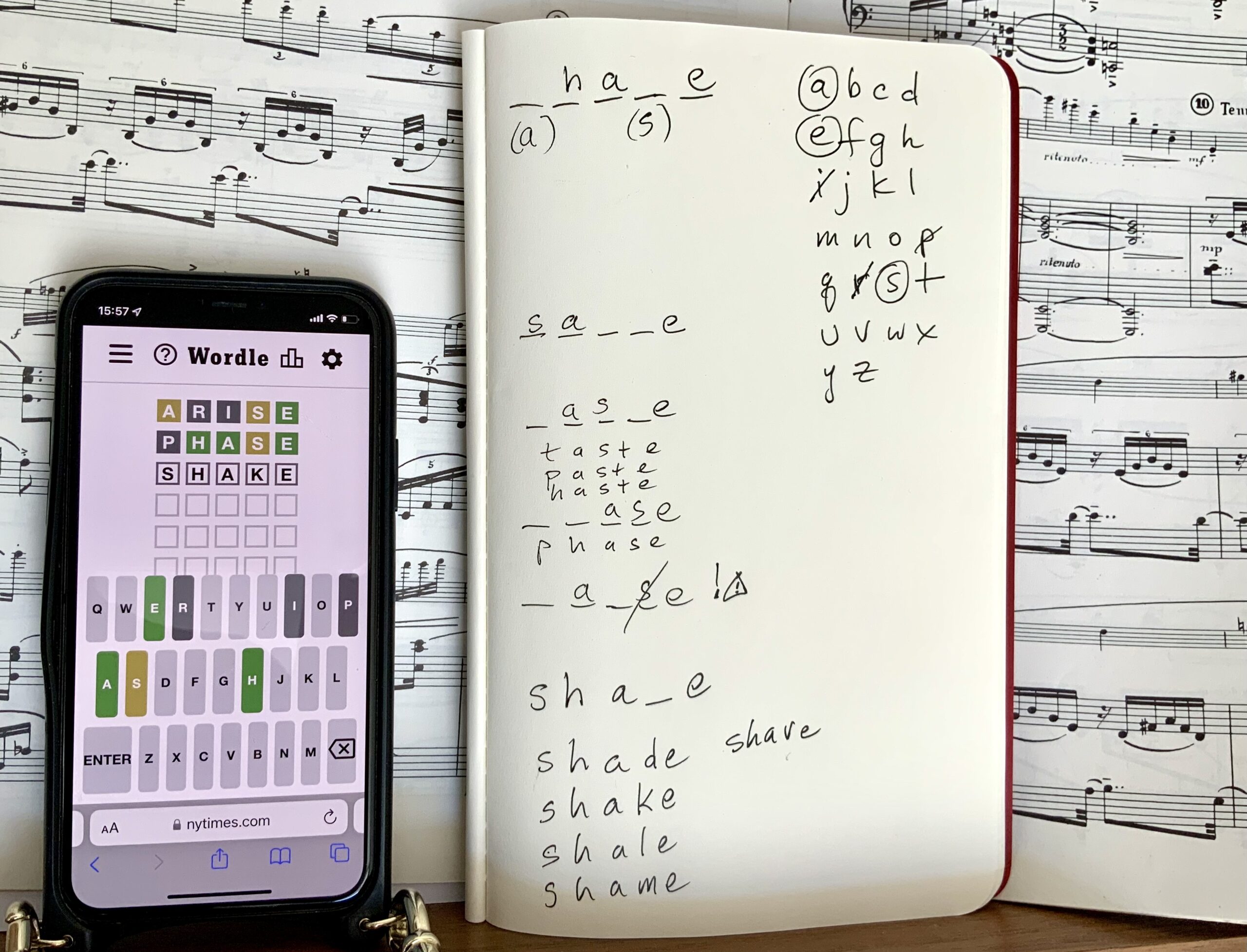

The flow principle explains the viral success of the The New York Times’ “Wordle” game, which keeps about two million Americans in “flow” mentality for 10 or 15 minutes daily trying to figure out the word of the day. It challenges us just enough that we enjoy playing with neither frustration nor boredom. Some of us have perhaps become a tiny bit addicted…

Likewise, you might work through the music you are playing, taking the figurations, intervals, dynamic and rhythmic patterns, or note-groupings and playing around with them, inventing alternate versions and variations. This is an engaging way to gain control over the musical elements (rhythms, intervals, dynamics, etc.). While such procedures may appear to be digressions from the work at hand, they enlist creativity, and in my experience, produce superior results.

Playful curiosity can be the best tactic for even the most tedious work, for instance, controlling finger movement during rapid passages—a dexterity required by most instruments. Rather than mind-numbing repetition for the sake of repetition, there can be pleasure in the non-judgmental observation of what is going on. “What exactly is my fourth finger doing?” is a more satisfying and productive approach than “I have to make this work NOW!” Once the best movement is found, it will be a pleasure to repeat!

What then can we do to help our children or students—or ourselves—stay in this felicitous zone?

We can tread lightly when we observe our children “goofing around” at their instruments. When we see our small pianist joyfully throwing their arms onto the piano, pedaling to produce a sonic storm worthy of a horror movie—resist the temptation to chastise the digression. Instead, witness the joy of their exploration! If we snuff this out, music might become just another task—a heap of notes to be “gotten” correctly, as if that were the goal.

Teachers also can respect this “goofing around”, even while obviously needing to get work done. We should strive for balance. A master teacher once told me that if neither the student nor teacher were laughing in the lesson, something was wrong! If you are a parent, do not assume that a teacher who makes the lesson fun is inferior to a teacher who makes everything a “serious” chore! BEWARE, again!

The idea that Western classical music is “serious”, and therefore must always be approached seriously reminds me of a scene in Stanley Kubrick’s film “The Shining”. Jack Nicholson’s crazed character—a writer also named Jack—scrawls over and over “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”…check out the movie to see what that leads to, but don’t watch it alone!

Indeed, research has shown that the lack of play not only leads to dullness, but to reduced social and mental development, depression, and criminal behaviour. According to Dr. Stuart Brown’s TED Talk, “nothing lights up the mind like play”. Play leads us toward creative thinking. And even performers, whose task might appear to be “re-creative”, can’t afford to lose contact with the composer’s creative spark.

The ideal learning process circles back and forth between goal-oriented ”work” and free exploration—“play”. Whether we are a student, professional or amateur, continuing to play when we play music, using our creative powers, inventing games and challenges as we practice allows the spark of joy in our playing to continue undiminished.