Movers and Shakers: Pheroza J Godrej

While Dr Pheroza J Godrej is best known for her work and writings in the field of art history and the environment, one of her many passions and interests is Western classical music. In this, as in so many other areas, activism is her hallmark. She has taken her keen engagement with music into the vital field of music education, notably in the work being done by the Mehli Mehta Music Foundation. In this exclusive in-person interview, she talks of the vision and plans of the Foundation, the current state of Western classical music in India and its key movers and shakers, and her own personal musical journey.

Nikhil Sardana: Given the many areas of your deep involvement and activities, in the environment, art history, curating, writing, how do you manage to fulfil your commitment to the promotion of Western classical music?

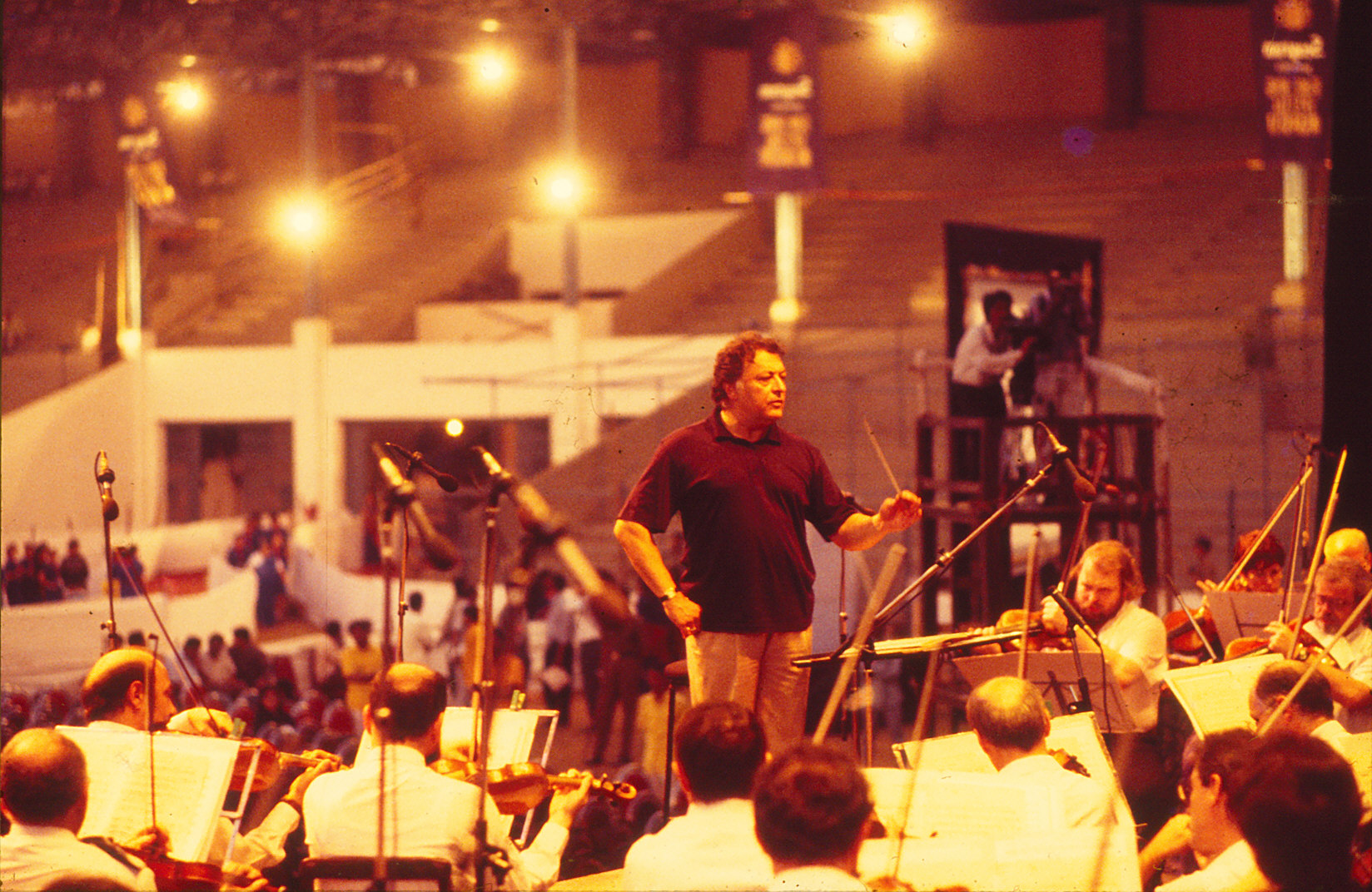

Pheroza J Godrej: I don’t work for too many organisations in the Western classical field. I have a commitment to the Mehli Mehta Music Foundation from the day of its inception. And even prior to that, when we did one concert where we didn’t have a banner of the MMMF. I’m referring to the first Zubin Mehta concert that came with the Israel Philharmonic just at the time when India and Israel were establishing diplomatic relations. Thereafter the Foundation was started. We took the involvement and help of Mr Nani Palkhivala at that time. And of course Zubin, Zarin Mehta etc.

Subsequently, it was the influence of my enthusiasm on my son who started helping Giving Voice to India which is basically giving vocal training to emerging singers in India. Artistes such as soprano Patricia Rozario, OBE, who was born and raised in Bombay, made her career outside India, and wanted to give back was one of those, and I was very happy that my son Navroze with his passion and interest in voice was supporting things like that. Indirectly, I do support her organisation and then there’s of course the National Centre for the Performing Arts. But when I was a young girl, my mother supported the Time & Talents Club which is the oldest Western classical music organisation. And there was another organisation called the Bombay Madrigals Singers Association (BMSO). And she supported them financially, a little bit, because these were organisations which have to give back to society. Time & Talents has to spend all their funding giving back. It is not that they can build up a corpus like the Mehli Mehta Foundation and plough it back into music. BMSO, tragically, doesn’t exist anymore, but Time & Talents does. Whenever they have concerts, one supports them. By the grace of God I have been able to sponsor some of their events. So the involvement is almost generational now that I am talking to you. At least in Bombay city, these were the organisations. And then many others have come up. Alfred D’Souza started the Stop-Gaps Academy. Before he started the academy he was performing and giving recitals. So there have been, and continue to be, many over the years, but yes, funding is limited because you cannot spread it all over. My husband and I do, however, try to spread it all over. I definitely try to do it personally and we sometimes request the trustees on our Foundation (we are not on our Foundation, we’re independent and our trustees are very independent).

NS: As a member of the Mehli Mehta Foundation, could you outline the scope of the Foundation’s activities and its vision for the dissemination of Western art music?

PJG: I think our Chairman will not like me stepping on her toes and I won’t step on her toes! But we are a group of like-minded individuals, both men and predominantly women, who felt very strongly that Western classical musical talent was in danger of being being drained from India. How do we get them back? How do we capture their imagination to come back and help the next generation because when we were growing up, we were given a piano or a violin or a cello to go and study.

I studied up to Grade 5 piano with the great Shanti Seldon both practical and theory. I hated it because I was forced to go and do it and I wish that both Shanti and my mum had not made it such a terrible chore for me that you have to appear for the exams. It was a form of discipline which the Mehli Mehta Foundation does not follow. That’s why we have huge numbers. On the other hand, neither the kids nor the parents have the commitment today and can drop out at any stage! Of course, the easiest thing is that if you can’t afford an instrument at least you have your voice, so join the choir. We have got from babes-in-arms with mummies and grannies coming to the Foundation for classes. And as the children have grown up they’ve gone into higher divisions (not grades because we don’t have exams!). We try to bring in as many teachers, short and long-term, to teach them. But, most importantly, where we are all struggling and suffering is in the lack of teachers. We need good teachers. So we have got a programme for these outstation, well-established musicians to come and focus on the teachers. Teachers, being teachers, don’t like taking instructions from other teachers. So that’s another problem. I for one strongly believe that if guided properly, they can be made to understand that everybody cannot go abroad, so grab this person and learn everything they have to offer you in this one year that they are here, or even in this one month. That is why we can have over a hundred children on the stage when the teacher comes from Barcelona. She is not a threat to any of our teachers as much as a fact that even our permanent teachers are not a threat. The proof of the pudding is how many students want to go to which teacher. It’s been a slow process but I think it’s a good process.

So coming back to our activities, we had started a festival. We found that many professionals like doctors or musicians, who are based elsewhere, do come back to Bombay, generally in December, to visit parents and family. That gave us a platform to start the Sangat Music Festival. And it ran very successfully for almost 21 or 22 years! But to be very honest with you, it didn’t achieve its final goal of nurturing local talent because the local talent couldn’t just depend on our concerts. One reason was that they worked voluntarily, at a cost to their jobs which may have been on a monthly / hourly/ weekly basis to come and practice. Secondly, when music was given to them months before the concert, they didn’t really take it very seriously. So they were doing their first rehearsal when these professionals, who also gave up valuable time, came to teach them.

NS: It is said that when the Foundation was set up in 1995, Maestro Mehli Mehta did have some misgivings about lending his name to something that didn’t have a certain standard. (I am quoting Mehroo Jeejeebhoy here). Of course, he was later happy with the work being done by the Foundation. How would you chart and evaluate the progress the Foundation has made?

PJG: There are two things here. If you look at quantity or the number of students that come to us and the number of performances by them, it’s been a huge learning curve to bring us to the other word “quality”. Every parent, anywhere in the world, wants to see their child on the stage. But if your child is not prepared, the Foundation has to say so. Just because you’re Mr and Mrs so and so… and you have put your child in the class and we’re having a concert and if he or she doesn’t know how to observe the teacher, take instructions from the teacher, be inattentive and fidgety, not focus on what they’re there on the stage, it’s not a given that you will be allowed to perform. We provide the opportunity, but standards have to be maintained.

Sometimes we have had to find the balance between quantity and quality, and we have been very hard on Mehroo to be very hard on the teachers because that’s where it starts. None of us go into the classes. That’s not our job or what we have volunteered for. There are times when it is embarrassing to sit in the NCPA Experimental Theatre and hang your head in shame. And parents realise that as well. So for voice you have to be very very careful. It’s great to say we have over 150 kids!

Another thing we did – we had our children from the Discover Music School, we have NGOs coming in, we have children from the schools in the suburbs coming in, we’ve had children from the Blind School coming in, and you can immediately spot them on the stage because obviously the visually impaired are so focused on what they are doing and their voices have been so well trained that they stand out. So over a period of time that has happened. This is also the feedback that we have got from the visiting teachers. Another thing is that you create music for enjoyment. But before the enjoyment there is a lot of hard work. And discipline is one of them. It starts at age 5. I think that was a reservation Mehli Mehta had. Another thing is instruments, teachers. So what he did, he did excellently. He sensed the top young musicians. You know he always had one young player in the orchestra with either a piano or violin or whatever. And they won competitions. They were not somebody that a friend or friend of the family had recommended or anything like that. And they are the ones who come and we encourage our teachers to come in observe the discipline that they bring to the stage. From his point of view he’s offered this unconditionally, if you all can raise the money over the years, whether it’s from the New York Philharmonic, Yuja Wang, Lang Lang, …they’ve all come, you know. And we encourage our teachers to come and interact with them because students are too young. The conductor of the Australian World Orchestra that came this September, gave a class at the Foundation, and 16 of our children played with the orchestra; it was a huge success! But those 16 have been with us for so many years. And we can’t come to the NCPA level because there they practice for 8 hours a day. They come to class every day, and the proof is there in the concerts. So the reservation in lending his name was that “is this going the way of the other societies in Bombay”?

NS: In 1957, the then Prime Minister, Pt Jawaharlal Nehru, wrote to his Information & Broadcasting Minister to share a letter sent by a Mr Desai of Bombay. Nehru expressed the concern, “I have been rather worried by the progressive disappearance of Western music from India. Bombay is practically the only centre left, where this is encouraged.” 60 years down the line, there is still a popular perception that Western classical music has made no significant impression outside of Mumbai. Do you agree with this perception?

PJG: You know we are so close to Western classical music that I don’t really have to distance myself. I think we’ve made 0.5% of a dent even in Bombay. Because the two communities, traditionally identified with Western classical music were the Christian community and the Parsi community. And wherever these two communities thrived there was some semblance of the Western classical music tradition continuing in the 60s and 70s.

But there was a reason for it. There was a brain drain. There were no IITs of Music coming up. There were no IIMs of Music coming up. These were all started in the 50s and the 60s and due to enlightened families they got enlightened architects to come and build these institutions. IITs were started in collaboration with the Germans and Russians – and these are nations with excellent musicians, why didn’t we think of it? I think we missed the boat over there. But at least from 1966 to ’69, the NCPA started in a very small way thanks to the vision, once more, of the Tatas – Mr JRD Tata.

It was JRD Tata who said we will start the National Centre for the Performing Arts. It was housed on one floor in the Bhulabhai Desai Memorial Institute. And I remember the day when this happened and I laughed. I was there at Madhuri Desai’s house and she said – “I have given the second floor of Bhulabhai. Now we have Akash Ganga.” She had already moved from Hasman Bungalows where she lived where all the artists were nurtured – Hussain, Alla Rakha, Ravi Shankar, Shamim Ahmed Khan, Tyeb Mehta, even NID was given a space over there. And Madhuri Desai said “I’ve given it for 5 years” to which JRD Tata asked “How much will you charge for this place”. She said “One rupee a year. Give me five rupees for five years.” This is the truth. And that’s how the NCPA started. She said, “Why don’t you also take over this dump in the front of my house” which became the Tata Garden maintained by Tata Electric. So these were connections which had the same vision as Pandit Nehru and as Dr Bhabha and who did they bring? Narayan Menon – All India Radio. But by that time the musicians had gone! People used to have concerts in their homes. There were only Patkar Hall, Bhulabhai Hall, Tejpal Hall (where we hardly had any concerts) and Birla Matushri Hall. There were only these theatres. Patkar suited the Western classical music genre. It was a 600-seater auditorium. We managed. All these auditoriums had Parsi managers!

Sangeet Natak Academi was established in the early 50s. I don’t think their core focus is only Indian… I mean we’ve had this culture… Look at the language we are speaking today. And there were really good musicians like George Lester on the cello, Adrian D’Mello on the piano, Tehmi Guzder for the piano, Shanti Seldon used to play on All India Radio! AIR had a once a week concert program… gone! Everything just gradually disappeared. And our local TV channels even today don’t do anything on the national channels for Western classical music. Because it is so sponsor-driven! Even the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting doesn’t look at it. It needn’t have come to these dire straits where everybody was concerned about what was happening to Western classical music. After all, look what they have done in Japan, China, Singapore, Malaysia, etc.

NS: Does your vision of the future of Western classical music encompass looking at other parts of the country, most notably the other metro cities?

PJG: 100%. What Anthony Gomes and the Gomes family of Furtados have really done is put their money where their mouth is, when they started the Con Brio Festival. It started with a piano festival and that’s when we discovered that there are so many young people still learning the piano in Trivandrum, Kochi, Chennai, Bangalore, Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta and Pune. Who are their teachers? Where are they coming from? What are they doing? So this piano festival has become very good and there again we have had this 100% support of some. Just as soprano Patricia Rozario has supported voice, Marialena Fernandes has supported the piano – another girl who has always come back to Bombay to see her family, always has had a concert through Time & Talents Club, performed… people come to hear her because she really is a good musician. It’s not just that she is one of us Bombay girls. She is really a good musician. And look what she is doing. Like a soprano, a pianist’s career can go on for much longer. And she is nurturing a whole new level of students who are coming to her from the old Soviet states who have no teacher left because funding has dried up.

NS: More than any other community, the Parsis have been patrons and supporters of Western art music. What would you ascribe their great understanding of and affinity with this music?

PJG: I think we were just raised on a diet of this through our parents most of us. But most of us are 65 / 75 / 85 and we also know the spending capacity when it comes to buying tickets for these concerts. We are an ageing community. Yes, some of us have done extremely well so we can be sponsors. But there are others around us who have also grown, who go to Bayreuth and hear the Ring Cycle. I know somebody from Delhi who is going for the 12th year for the 12th Ring Cycle – not raised on a diet of Western classical music but has cultivated it or created it. And also in the past we had small support and sponsorship. I remember the first bank that sponsored the Zubin Mehta and New York Philharmonic that came and played at the Shanmukhananda hall was Citi Bank, Bombay. The orchestra was on a world tour, and Nanoo Pamnani sponsored that, he was head of Citi in India at the time, and he brought out a lovely LP of the concert because there were no CDs and cassettes in those days. Now there are many sponsors coming forward, there are many organisations coming forward. There is consciousness in the upwardly mobile Indian generation who has the facility to travel, their children are being educated abroad, they’ve got a sense of not only attending concerts but going to museums, and appreciating many art forms.

NS: Has that resulted in an attitudinal change towards the possibility of art forms as a profession?

PJG: Art history has become a whole new career, museums here are doing well. But again, we have a dearth of curators and you cannot do this in two years over a part-time course. Conservation has become a career. Tuning musical instruments and maintaining them has become a career at one level as well. There are definitely more patrons coming forward. The same is applicable to Indian classical dance and music. You know Shubha Mudgal has single handedly popularised vocal Indian classical music to the masses. Of course Zakir in the tabla is a class apart. Listen, I’m not even in this field, and am giving you names because they have affected my growth.

NS: Do you have any favourite works from the classical repertoire? Please share them with our readers.

PJG: If I could go back and play the piano, which is my instrument, I would unhesitatingly go to a concert where there is Chopin and Rachmaninoff. I am a great Romantic at heart. Of course Beethoven as well. If I had to start again, I would learn all the Nocturnes, Waltzes, I would do everything my mother and Shanti Seldon told me to do. Not to play a concert but for my own enjoyment.

All Images © Mehli Mehta Music Foundation