Robert Schumann’s Scenes from Childhood (Kinderszenen), Op. 15 is one of those rare piano works that is both a staple of the standard teaching library and frequently performed by concert artists. Nearly 200 years after its publication, perennial favorites such as Of Foreign Lands and People (Von fremden Ländern und Menschen), Curious Story (Kuriose Geschichte), and Dreaming (Träumerei) remain popular pieces for both study and performance. These 13 late intermediate to early advanced level character pieces highlight many of the characteristics found in music from the Romantic Era, such as the expansion of musical textures, the exploration of new harmonic language, and the development of more complex rhythmic relationships. When compared to Schumann’s other pedagogical work, Album for the Young, Op. 68, in which composers from Peter Tchaikovsky to Lowell Liebermann have paid homage with their own albums for the young, Scenes from Childhood has not been widely replicated—until now.

Composed in the year 2000, at the dawn of the 21st-century, Russian born composer and pianist Lera Auerbach (b. 1973) honors the artistic and pedagogical legacies of Robert Schumann with her collection, Images from Childhood, Op. 52.

Auerbach’s set of 12 intermediate level character pieces is full of musical exploration and inquisitiveness. These themes serve as a uniting factor throughout this diverse collection, and in an effort to pique a pianist’s curiosity, Images from Childhood begins with a seemingly simple question. Question, the first piece in the set, features a repeated melodic idea that is supported by ever-changing harmonies. Despite this persistently repeated melody, the questioning phrase never quite feels answered or resolved. The incomplete feeling is heightened by an asymmetrical seven-beat phrase, a dissonant melody, and ever-changing chromatic harmonies that avoid a tonal center. After all this exploration, perhaps the ultimate conclusion is that this musical question, just like many of the big questions in life, has no definitive, clear-cut answer.

While not a formal theme and variations, the opening eight measures of What a Story!, Auerbach’s second piece in the collection, essentially function as a theme followed by four semi-statements/variations of the melody. Each statement/variation explores changes in articulation, meter, register, tempo, pitch, and texture. For example, the opening phrase in measures 1-4 is playfully disguised in measures 17-20 with the help of a new time signature and broken intervals. Throughout this passage nearly all of the notes in both hands can be traced back directly to measures 1-4. This clever camouflage serves as proof that the melody is always close at hand, not to mention closely played within the hand! With few distances larger than the interval of a 6th, this piece fits comfortably in the hands of pianists of all ages.

Vibrant sound colors, precise articulation, dissonant clusters, and a bit of humor prevail throughout Stubborn, the ninth piece in Auerbach’s collection. Initially the spartan LH ostinato clusters feel a bit monotonous and heavy. Yet, when combined with the tango inspired RH melody that dances across the middle, high, and low registers, the clusters provide not only a steady heartbeat but they also add a hint of madness that verges on the edge of hilarity as the piece progresses.

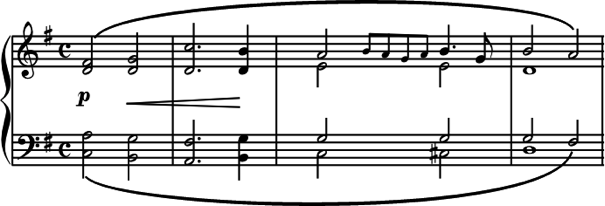

In what is perhaps the most obvious nod to Schumann, the final piece, Prayer, most directly recalls the simplistic beauty and serenity of The Poet Speaks, Schumann’s final piece in Scenes from Childhood. Not only does the contour of Prayer’s opening melody and bass lines hearken back to the opening of The Poet Speaks, but the rhythm isnearly identical as well.

Like so many other pieces in Images from Childhood, Prayer does not fit into a conventional tonality. However, the four-part choral writing, complete with a calm rhythmic pulse and predictable phrase structures, helps to mask any moments of unease or uncertainty that might develop due to a missing tonal center. Throughout the piece, several unexpected harmonic moments arise and rather than detracting from this musical prayer, they add to the reverence and awe of each newly discovered chord and sequence of chords. It is because of Prayer’s simple texture that these magicalaural moments are so effective. Purposefully placed as the last piece in Images from Childhood, Prayer serves as a peaceful, contemplative coda to this retrospective of youth.

Question, What a Story!, Stubborn, and Prayer are just a few examples of the rich musical explorations awaiting pianists in this collection. By honoring both the artistic and pedagogical legacies of Robert Schumann’s Scenes from Childhood, Auerbach’s Images from Childhood serves as a bridge between the 19th and 21st-centuries. Schumann’s pieces are a product of the Romantic Era through their exploration of textures, rhythms, harmonies, and the development of larger cycles of pieces. Likewise, Auerbach’s work reflects the 21st-century with an emphasis on dissonance, clusters, changing meter, and the use of multiple pedals to create depth and textures via sound colors.

Interestingly enough, the pedagogical connections between Scenes from Childhood and Images from Childhood are not the only links Schumann and Auerbach share. The creative ties between these composers run deep. Both individuals were clearly established in their careers when writing these collections. And, coincidently, Schumann and Auerbach were nearly the same age when composing their works, ages 28 and 27 respectively.

Paired with their composing is a steadfast devotion to the written word. Schumann was well-known for his essays and articles on music, and these papers were regularly featured in the German journal Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung.1 He was equally devoted to writing personal diaries, letters, poetry, and other short literary works as well. Auerbach herself is a published author of prose and poetry. With works in both Russian and English, she was named Poet of the Year in 1996 by the International Pushkin Society and continues to write and publish in a variety of literary genres.2

The effort to unite creative endeavors into a unified artistic quest is not unique to Schumann or Auerbach. Many other composers and musicians have explored literary pursuits in conjunction with their musical works. However, Schumann readily admits to the struggle he felt with his two creative passions. In a letter written at age 20 he lamented, “If only my talent for music and poetry would converge into a single point, the light would not be so scattered, and Icould attempt a great deal.”.3 With Auerbach there appears to be no struggle or scattered points of light regarding her artistic pursuits. As a composer and pianist, as well as conductor, writer, and visual artist, a swift current of creativity, originality, and substance flows throughout this 21st-century renaissance woman. Given this vibrant background, it is no surprise that such a unique compositional voice emerges and radiates throughout Images from Childhood.

Anne Midgette, former music critic for the Washington Post newspaper, eloquently states of Auerbach and her works,

“Those fearful of contemporary music may think of it as dry, cerebral, atonal, and scary. Lera Auerbach, a Russian-born composer, delivers lots of fire and passion in music that is generally tonal. Indeed, she offers 18th-centuryforms and a 19th-century sensibility (that of the brilliant virtuoso) expressed in a 21st-century vocabulary.”

What an interesting and thought provoking perspective on a living composer/pianist and her relationship to the broader scope of music history! New perspectives, interpretations, and contributions to time honored works and genres are fundamentally necessary. Without them, music becomes a stale relic of the past. Images from Childhood is clearly not a stale relic. Rather, it is a collection that is effortlessly fresh and inquisitive while simultaneously feeling like a beloved classic. Auerbach’s vibrant compositional voice reminds us that classical music is very much alive in the 21st-century and eagerly awaits a new generation of pianists.

End Notes

- Platinga Leon, Romantic Music (New York: W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1984), 221-22.

- “Lera Auerbach Biography” Sikorski Music Publishers Artist Biographies, accessed September 7, 2021.

- Platinga Leon, Romantic Music (New York: W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1984), 221-22.

- Anne Midgette, “Music Review: CrossCurrents: Composer Lera Auerbach, Cellist Alisa Weilerstein,” Washington Post, last modified Monday, May 4, 2009.

By Lera Auerbach

Copyright © 2008 Hans Sikorski Musikverlag GMBH

International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved.

Reprinted by Permission of G. Schirmer, Inc.

- 1. Question, mm. 1-4

- 2. What a Story, mm. 1-4, 17-20

- 9. Stubborn, mm. 1-4

- 12. Prayer, mm. 1-4