WIENER BLUT: THE ESSENTIAL STAATSOPER EXPERIENCE

DAY ONE

Wednesday 19th September was a red letter day. I turned up well in time to take my seat in the orchestra stalls not knowing what to expect. At 8 o’clock sharp two men in full evening dress strode on to the stage and launched straight away into lieder. Thus began one of my most memorable evenings at the opera. Theirs was a no nonsense approach exhibiting the highest professionalism and seriousness of purpose. These two gentlemen were Günther Groissböck and Gerold Huber. Groissböck, the 42 year old Austrian bass barihunk, is at home both in lieder and opera. His repertoire includes Brahms’ Four serious songs, Schubert Winterreise and Schwanengesang, Mahler’s Rückert-Lieder and Wolf’s Michelangelo-Lieder as well as the roles of Heinrich der Vogler (Lohengrin), Rocco (Fidelio) and Baron Ochs (Rosenkavalier). He is to make his Royal Opera debut in the 18/19 season as Fasolt in Wagner’s Ring.

The singer was partnered ably and impeccably by 49 years old German pianist Gerold Huber well known as the regular accompanist of Christian Gerhaher.

The recital opened with one of the most challenging and heavy song cycles in the repertoire. Written in Vienna in 1896 this cycle of four late songs was published by Simrock as Op. 121 for low voice and piano. The first performance was given in the same year by two Dutch musicians in Brahms’ presence. These songs on words from the Bible were composed in anticipation of his friend Clara Schumann’s death. She had suffered a stroke earlier that year.

The singer was in full command of his voice with outstanding control over dynamics and range. Huber provided excellent support always alert to every vocal nuance.

Next on the programme was Robert Schumann’s Eichendorff Liederkreis op.39. This cycle was written in 1840 his “year of song”. It is his best known cycle and probably one of the most famous in all 19th century romantic lieder. The two musicians collaborated perfectly and the twelve songs that comprised the cycle had equal significance. After the heavily charged Germanic first half came a selection of Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov romances. Groissböck began the Tchaikovsky group of five songs with the famous op.6 setting of “None, but the lonely Heart”. The last Tchaikovsky romance was the Don Juan's Serenade with its virtuosic piano accompaniment. Six Rachmaninov settings made for an impassioned end to the official programme. Three encores followed, Non t’amo più by Tosti, Core n’grato and Die Erlkönig. What a marvellous recital that left the audience hungering for more!

DAY TWO

Of my week spent in Vienna this was clearly the highlight. I also saw at the Wiener Staatsoper two operas and a ballet. On 20th September it was Jean-François Sivadier’s production of La traviata by Verdi. The French stage director working with French coloratura soprano Natalie Dessay described their collaboration in the 2012 documentary film Traviata et nous (Traviata and Us). In this film the three main protagonists (tenor Charles Castronovo and baritone Ludovic Tézier join miss Dessay) are seen marking their roles in less than full voice preparing for the production’s debut at the festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

The story and music are so well known that I won’t dwell on them further. Suffice to say that Sivadier’s co-production with the Aix-en-Provence festival was a disaster. Turning the glamorous demi-monde of 19th century Paris in to a tawdry contemporary street-life scenario, it is surprising that in its long and illustrious history the Wiener Staatsoper has only had four productions of Verdi’s perennial favourite masterpiece. Even more surprisingly it was seen here for the first time more than hundred years after its premiere in Venice as recently as 1957.

All in all the mise-en-scène was uniformly disastrous. Sets and choreography made no special impact. Pavol Breslik has a beautiful light quality to his voice which he showed off in his opening Brindisi. Although the voice in “De miei bollenti spiriti” was not large the phrasing was splendid in the cabaletta with good high notes. As Alfredo’s father, Giorgio Germont (Sir Simon Keenlyside) proved a very disappointing choice. The British baritone has wide experience in a variety of roles in opera as well as the concert platform. Although normally quite at home in Verdi he seemed out of sorts on this particular evening. Legato singing and breath control were lacking resulting in variable pitching. His big aria Di Provenza il mar and act II duet with Violetta went for nothing.

Any Traviata is made by the quality of its Violetta. Full marks to Albina Shagimuratova the young Russian singer from Tashkent who is taking the operatic world by storm for ticking all the boxes. Yet her interpretation came to a sum less than its parts. In her act I scene “Ah fors’e lui” she displayed a warm controlled legato. Her cries of “gioir” with high C’s and B flat and the interpolated high E flat displayed impeccable coloratura. Her voice also is large enough to ride the concertante sections of the act II finale. She had a beautiful top A diminuendo to Addio del passato in act III. Her duet Parigi o cara when reunited with her lover was beguilingly beautiful and her death notably emotional. The orchestra under the direction of the ever fresh Evelino Pido delivered Verdi’s orchestration sumptuously as befits the best opera orchestra in the world.

DAY THREE

On Friday September 21st was another very popular outing in the form of Adolphe Adam’s ballet Giselle sandwiched between La traviata and the less well known French opera Werther.

Giselle or The Wilis is a romantic ballet in two acts first performed in Paris in 1841 by Italian ballerina Carlotta Grisi in the name part. It was an unqualified success becoming hugely popular across Europe, Russia and the US. The traditional choreography that has been passed down to the present day derives primarily from the revivals staged by Marius Petipa during the late 19th and early 20th centuries for the Imperial Ballet in St. Petersburg. Petipa was probably the most well-known dancer-choreographer of all time and certainly the most influential.

Giselle is a masterpiece of classical ballet. The story tells of the tragic romance of a beautiful young peasant girl who falls for the flirtations of the deceitful disguised nobleman Albrecht. When the ruse is revealed she dies of heartbreak and the false count must face the otherworldly consequences of his careless seduction. The librettists Gautier and Saint-Georges were inspired by prose by Heinrich Heine and Victor Hugo. Theophile Gautier recorded his part in the creation of the ballet; he had read Heinrich Heine’s description of the Wilis and thought these evil spirits would make a “pretty ballet”. He planned their story for act II and settled upon a verse by Victor Hugo called “fantomes” to provide the inspiration for act I. This verse is about a beautiful 15 year old Spanish girl who loves to dance. She becomes too warm at a ball and dies of a chill in the cool morning.

Heine’s prose tells of supernatural young women called the Wilis. They have died before their wedding day and rise from their graves in the middle of the night to dance. Any young man who crosses their path is force to dance to his death. These jilted young women have grown to hate man in the next world.

Adam was a popular writer of ballet and opera in early 19th century France. The music was written in the smooth, song like style of the day called cantilena as in the bel canto operas Norma and Lucia. Adam use several leit motifs one for each character and another for the idea of the flower test “he loves me he loves me not”. The Wilis also have their own motif.

Giselle was danced by Liudmila Konovalova. In act I her short mimed scenes were convincing and her dance steps kept to the minimum. In act II her mime had become fused entirely with dance. Her movements were mainly restricted to developpes and grands ronds de jambe. Her turns and leaps including pirouettes and grandes jetes were spectacular. Albrecht danced by Robert Gabdullin leant strong support in the pas de deux in both acts. The scenery sets and costumes were all traditional and the corps de ballet made a big impression in act II. Although the precision of their coordination was not razor-sharp they made for a convincing ballet blanc in full white bell-shaped dancing in geometric design.

By no stretch of the imagination can the musical score be called great but it is admirably suited to its purpose. It is danceable and has colour and mood attuned to the various dramatic situations and still exerts its magic today. The orchestra of the Vienna State Opera rose to its not inconsiderable heights in providing a living, breathing accompaniment to the dancing under the baton of Maestro Ermanno Florio. The spotlight shifted to give space to solo instruments as required while maintaining the beauty and expressivity of this visual and aural treat.

DAY FOUR

To round off my visit to the Staatsoper I saw the infinitely moving tragedy Massenet’s Werther on Saturday 22nd September. This is in four acts to a libretto by Blau, Milliet and Hartmann loosely based on the German novel “The Sorrows of Young Werther” by Goethe which was based on Goethe’s own early life.

Written between 1885 and 1887 it was rejected by the Paris Opéra Comique only to be accepted for its premiere in a German translation at the Imperial Theatre Hofoper in Vienna. The French language premiere followed in the same year of 1892 in Geneva. The next year saw its premiere in Paris and soon after it entered the repertoire at the Opéra Comique with over a thousand of performances in the next fifty years. Werther along with Manon remain Massenet’s two most popular operas and are performed all over the world today.

The action takes place in an undefined year in the 1780 between July and December. In July the widowed Bailiff is teaching his six youngest children a Christmas carol. Charlotte the eldest daughter dresses for a ball to be accompanied to by Werther since her fiancé Albert is away. As they leave for the ball Albert returns unexpectedly and his unsure of Charlotte’s intentions and is disappointed not to find her at home. Consoled by Charlotte younger sister Sophie he promises to return the next morning. Charlotte and Werther return very late; Werther is already enamoured of her. His declaration of love is interrupted by the announcement of Albert’s return. Charlotte recalls how she promised her dying mother she would marry Albert. Werther is in despair. Three months later, Charlotte and Albert are now married. They walk happily to church to celebrate the minister’s 50th wedding anniversary followed by the disconsolate Werther.

Albert and then Sophie try to cheer him up but he speaks only to Charlotte of their first meeting. Charlotte begs Werther to leave her though indicating she would be willing to receive him again on Christmas Day. Werther contemplates suicide; Sophie cannot understand his distressing behaviour though Albert now realises that Werther loves Charlotte. Charlotte is at home alone on Christmas Eve. She is re-reading the letters that she had received from Werther (the famous letter scene in act III). She wonders how the young poet is and how she had the strength to send him away. Sophie comes in and tries to cheer up her older sister, though Charlotte is not to be consoled. Suddenly Werther appears and while he reads to her some poetry of Ossian (the familiar solo Pourquoi me reveiller) he realises that she does indeed return his love. After a brief embrace she quickly bids him farewell. He leaves with thoughts of suicide. Charlotte has a terrible premonition and hurries to find Werther. An orchestral intermezzo leads without a break in to act 4. At Werther’s apartment Charlotte has arrived too late to prevent Werther from shooting himself; he is dying. Outside children are heard singing the Christmas carol while Charlotte declares her love and faints.

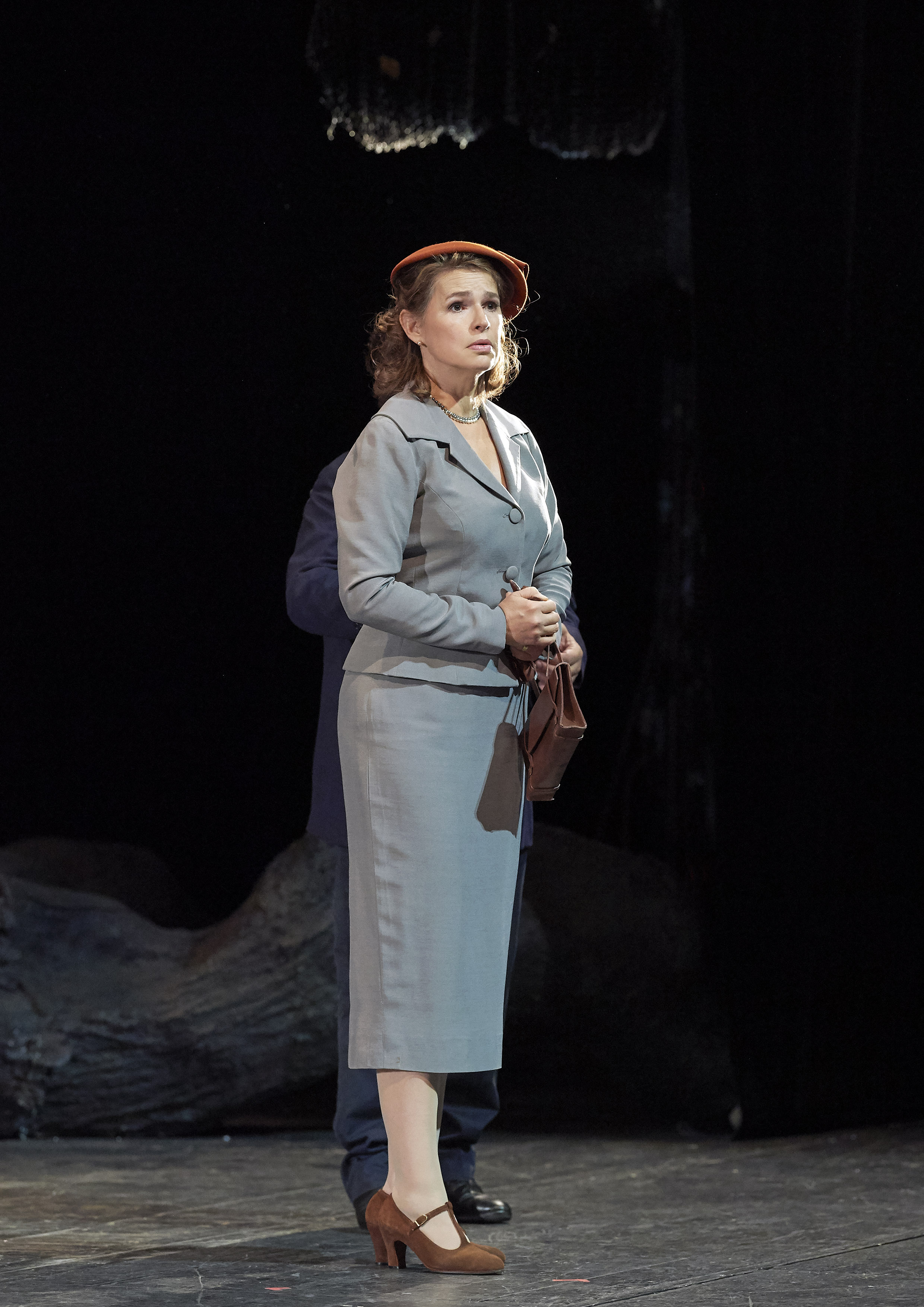

In the role of Charlotte was the French mezzo Sophie Koch. She studied in Paris and made a major success as Rosina in London. Her Wiener Staatsoper debut was in 1999 as Octavian and her roles range from Mozart to Wagner with an emphasis on the lyric mezzo repertoire. She turned in a beautiful performance as the love lost heroin Charlotte. Her voice is even throughout its range with resonant high notes and secure chest tones. Her understated rather than over passionate singing made for a highly sophisticated portrayal conveying the words naturally in her own language. It was just as well that the audience did not breakout in applause after her Letter Scene.

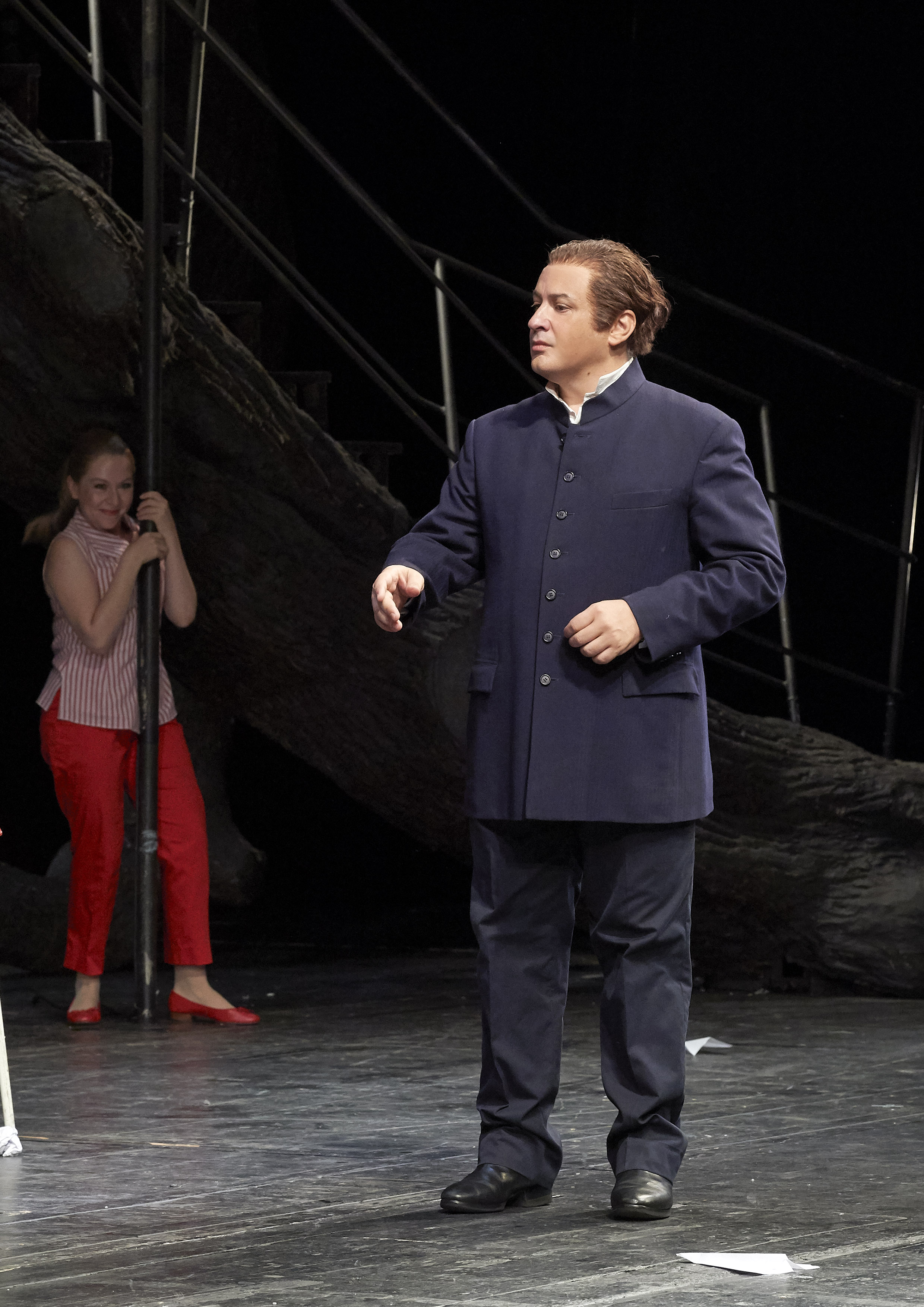

Werther was sung on the night I went by Stefano Secco. He was a real find with a gorgeous voice basically light lyric in character. He brought out the moody nature of the eponymous hero’s nature. He and Koch rose to the demands of their many duets flawlessly and his clarion-toned ode in act 3 gained considerable applause. Clemens Unterreiner in his role debut was a more than adequate Albert. This young Viennese singer has made a reputation for himself in a very short time in opera as well as in the concert hall. He sang with great beauty of tone and made the character convincingly life like. Conductor Frédéric Chaslin, protégé of Daniel Barenboim and Pierre Boulez, made his debut in 1993 at the Bregenz Festival. From 1999 to 2002 he was the conductor of the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra. Since then he has conducted all over the world in the most prestigious opera houses and festivals. The production was by the great Romanian American stage director Andrei Serban with sets and costumes by Peter Pabst.

This was one of the best evenings at the opera in recent memory- a dedicated cast of great singing actors (though not necessarily all big names), the Vienna Philharmonic and a very musical conductor, a great operatic tragedy that tugged on the heart strings and last but by no means least the very knowledgeable and courteous Viennese audience (the tourists had all gone home!).