What does the term ‘classical music’ mean to us in the 21st century?

Classical music means more than one thing and explanation is in order. Sometimes I make the distinction between big “C” and little “c”, but even that doesn’t fully solve it.

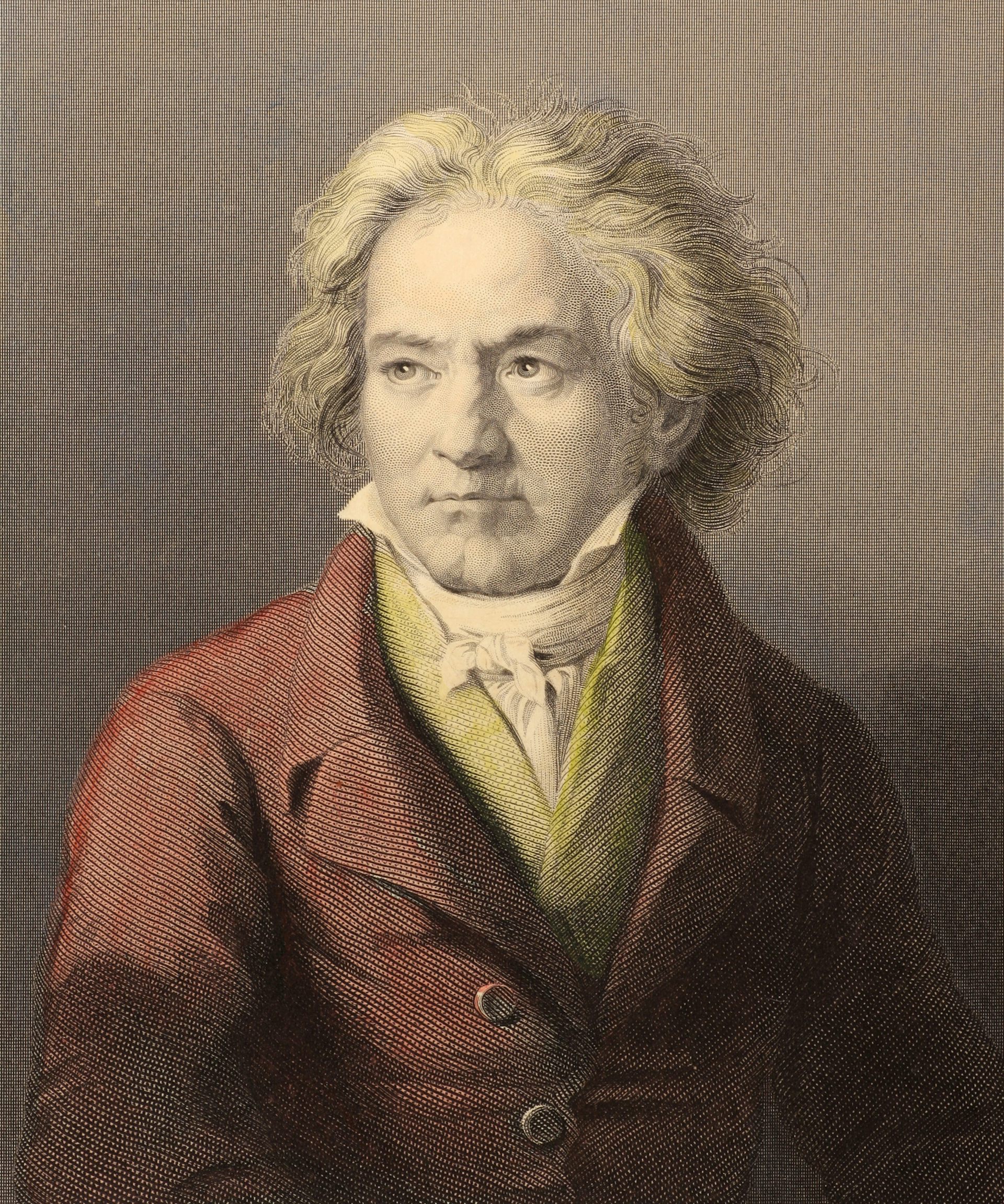

The starting point is this: the “Classical” period in music is generally described as encompassing the works of Haydn (1732-1809) through to Beethoven (1770–1827). Mozart (1756-1791) fits squarely in the middle. In my mind it conjures elegant harmonies, well–phrased melodies and logical, balanced structure.

Eventually, Beethoven (think late string quartets, Symphony No.9) redefined “Classical” style (not single-handedly, of course) and he constitutes what we define as an emerging “Romantic” period (c.1825-c.1910). But this starts even earlier in Beethoven, it’s just that it is tricky to definitively argue exactly when we flick the switch.

The truth is that we don’t instantly hit the “Romantic” period (or any period for that matter). We excruciatingly morph between artistic philosophies and aesthetic sensibilities over decades.

In the rear-vision mirror of history, it seems like a clear shift, but on the ground in real time, artists tend to exist between the cracks of established procedure and darkness. If genuine, they are moving from the known into the unknown (reference to Donald Rumsfeld unintended).

“Romantic” has overtones that are problematic. It’s a brave commentator who will argue that there are no “romantic” qualities in Bach (1685-1750). But again we are marooned on an upper-case, lower-case island. And so we paddle back to our “classical” mainland and contemplate what the generic term means to us now in the 21st century.

Classical music (okay, the sentence started with a capital, but let’s pretend it was a lowercase “c”) tends to be played by musicians reading quavers and crotchets from music stands. They have violins, flutes and trumpets. Or they sing, play the piano and so forth.

If musicians are playing an early music instrument such as a sackbutt or a viola da gamba this is riskier to categorise because these days we are more specific about an authentic “early music” scene, which could theoretically fall under the larger umbrella of “classical music” – but don’t expect early music enthusiasts to be happy about it.

If musicians are playing electric guitars and drum kits, it would likely be outside the orbit of classical music. But try telling that to Icelandic singer-songwriter Björk, English singer-songwriters Peter Gabriel or Elvis Costello, who are equally at home singing over a conducted orchestral string section as they are jamming with electric guitars and Marshall stacks. But they are legitimate (and impressive) exceptions, not the rule.

At its best, I think classical music represents a deep and highly developed musical listening experience. In theory, any instrument should not be excluded. It doesn’t have to be “Western”, it could be Indian for instance. I think it is more about the intent of the composer and musicians than the colour or shape of the sound-producing objects.

Perhaps this is the point in the article where I need to state that I am a composer. The author of this article holds shares in staves, clefs and note-heads (but also in computers and technology).

I have a love-hate relationship with Mahler (1860-1911). Yes, he’s dead (and white, and male). And at times I find his symphonies interminable, overblown: please-just-get-on-with-it. But he pushes the boat out in terms of structure over a long duration (often more than an hour) and I love the “intent”, the idea of this, and certain sections are simply magnificent.

Compare this to the television series Australian Idol. To Australia’s Got Talent. The Voice. Well-known three to four minute songs are halved to provide a vehicle for me-time.

It is a cultural abomination and societally, we are asleep at the wheel. Seriously, we should expect more of ourselves.

But this is not about pop versus classical. This does not have to be uptown versus downtown. It’s about our concentration span and the depth of listening experience.

A few years back, so-called “classical music” was under attack in this country (and likely elsewhere) for being elitist. Richard Tognetti (violinist extraordinaire and artistic director of the Australian Chamber Orchestra) effectively said, in an interview with Susan Chenery at The Australian, “we are elite, not elitist”.

Tognetti’s distinction is a useful one to make. We should be seeking, assessing and rewarding excellence in whatever guise it may come. Classical music (oops, big C again) is not automatically “better”. It can be anachronistic, poorly written, badly played and “dished up” (as Australian-born composer Percy Grainger expressed) in over-priced clothing.

But even in this new millennium, classical music has a few things going for it – principally an expectation that we are able to listen carefully for longer, uninterupted periods of time. If the music is any good, the performers skillful and dedicated, and the acoustic rewarding then we, the listener, might experience something wonderful beyond our imagination. That we should live so long.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.