Two to Tango

The tango has travelled far beyond Argentina and Uruguay to find a well-respected place in the classical music canon. To trace the journey of this musical genre (and dance style) is to unearth its strong links to its place and culture. By Beverly Pereira

Few other art forms evoke a mélange of polarised emotions like the tango does. The very word ‘tango’ conjures up images of a dancing couple locked in an embrace, guided by the spontaneity of the music as they swirl and swivel across the floor. There are moments of passion disguised as rage, feistiness shrouded by melancholy, desire and longing replaced by intimacy, and sensuality finding a common ground with bravado. While the exact origins of the tango are obscure, its history dates back to over a hundred years ago – precisely to the lower-income areas of Buenos Aires in Argentina and Montevideo in Uruguay in the 19th century.

The spirit of tango

It is known that the tango sprang from the streets as a result of the confluence of cultures and that human displacement was central to its conception. In the early years of the 20th century, millions of immigrants from Europe, notably a large number of Italians, poured into the two capitals in search of better prospects. A new form of rhythmic dance and music ensued – one that forged traditional polkas and waltzes with pre-existent dance and music styles such as the Cuban habanera and the African community’s candombe. The resulting form, tango, lent a voice to the conditions and emotions of the common man.

Early tango groups were small, mainly consisting of trios specialising in instruments such as the solo guitar, piano, flute, clarinet and violin. Besides its distinctive 2×4 and 4×4 rhythm, the music was characterised by the liberal use of lunfardo, the old street slang of Buenos Aires.

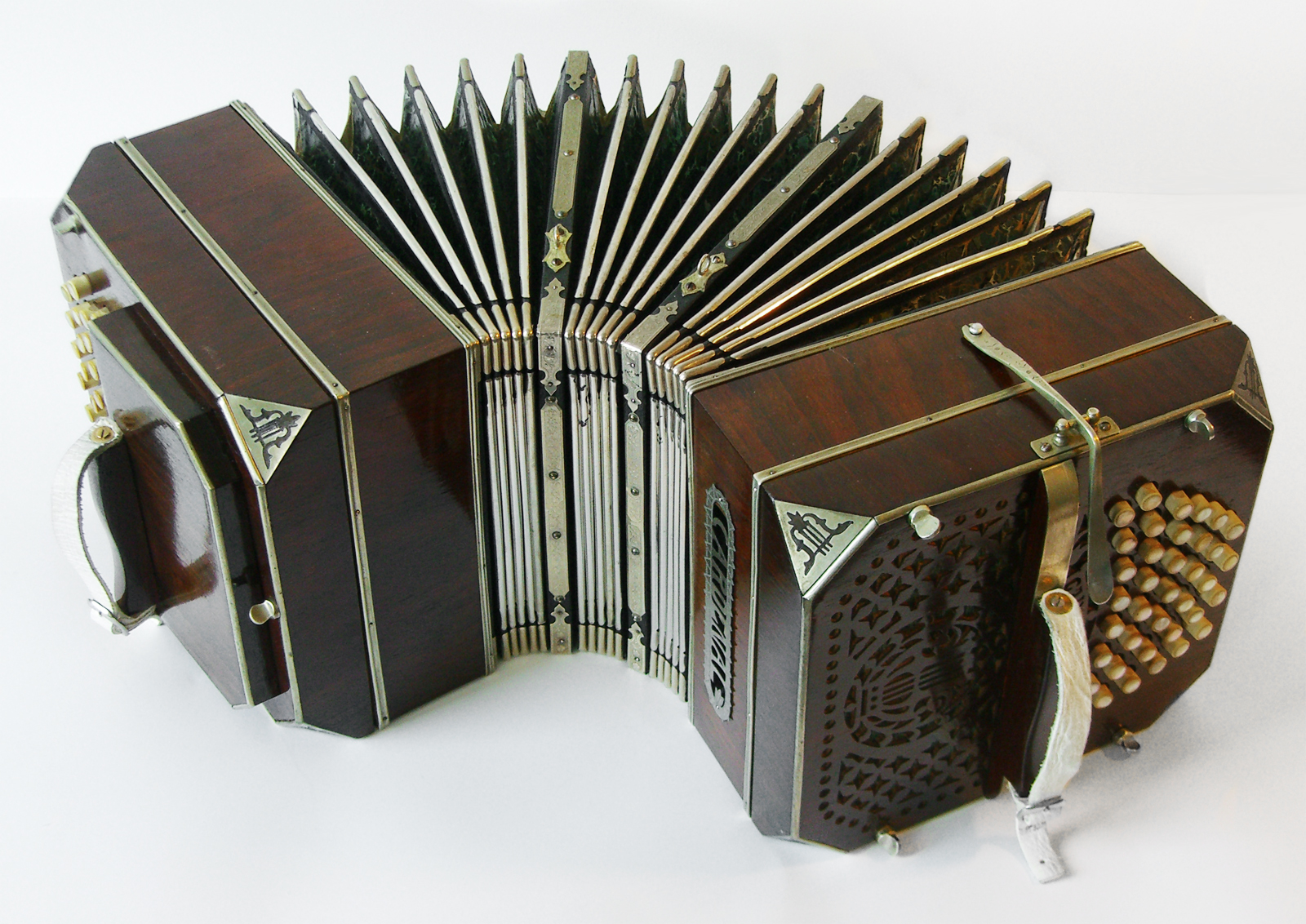

The bandoneon – tango’s signature instrument – found its way into compositions by 1870 when German immigrants and sailors brought the accordion-like instrument with them to South American shores. But it would only go on to become an essential instrument in tango ensembles from 1910 onwards. The bandoneon, invented by Heinrich Band for use in churches in Germany in the mid-19th century, is a small but powerful instrument with an incredibly rich range, flexibility and emotive quality. This period in tango history, known as La Guardia Vieja, or the Old Guard, lasted from 1895 to 1910. Its most notable representative was Ángel Villoldo, who wrote the very famous tango ‘El Choclo’.

When scores of tango dancers and orchestras made their way to European cities in the early years of the 20th century, it was the spirited social dance form that really introduced the rest of the world to the accompanying music. First, Paris was gripped by ‘tangomania’ in 1910; not long after, the craze hit New York and other parts of the world. The tango experienced a surge in popularity around the globe when it found its way into the 1921 Hollywood film The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, with the rakish Argentine Rudolph Valentino performing the slick dance.

The golden age

Back in Buenos Aires, the tango took on a new identity; lyrics and compositional structure were weaved into songs, and hundreds of recordings were being made. Once viewed as a prohibited dance, the tango was now beginning to earn a more respectable reputation. Its belated popularity can be credited to Carlos Gardel, one of the city’s most famous French-Argentine singers and songwriters. Gardel wove melodrama and empathy into his lyrical renditions of traditional tangos, which resonated with various sections of society. Gardel, who ushered in a new era of tango canción (tango song), continues to be revered in both Argentina and Uruguay.

Between 1935 and 1952, tango music and dance were performed by orquestas típicas (musical ensemble) consisting of over ten performers playing the piano, double bass, violins and at least two bandoneons. Juan d’Arienzo, a violinist and conductor, and pianist Rodolfo Biagi teamed up to give back to the people of Buenos Aires a faster-paced tango that soon became the characteristic style of the period. Soon, ever-evolving orchestra conductors such as Aníbal Troilo started to give singers importance all over again without forgoing the rhythm that was appreciated by dancers. But by the late 1950s, with the advent of rock ‘n’ roll, the popularity of dancing to tango music began to decline.

Nuevo Tango

If Gardel was the last big tango superstar in South America and beyond, it was Astor Piazzolla who revolutionised the tango and revived interest in the form. Piazzolla was a famous pianist and bandoneonist who once played with both Gardel’s and Troilo’s orchestras. Having left Buenos Aires to study classical composition in Paris with Nadia Boulanger in 1950, he decided to go beyond the traditions of tango. In doing so, he created Nuevo Tango – a fusion of classic tango with elements of jazz, learned during his formative years in New York, and Western classical music.

This new tango style appealed to listeners rather than to dancers who were unable to interpret the complex jazz rhythms. It enjoyed remarkable success across the world, even as it caused a mighty stir in Buenos Aires for trampling upon tradition. Although, it must be noted that traditional tango was still very much alive at the time, thanks to Osvaldo Pugliese and other tango purists. Piazzolla’s unique vocabulary challenged the traditional tango ensemble by incorporating two violins, two bandoneons, a bass, cello, piano and an electric guitar. Four Seasons of Buenos Aires, his suite of four compositions, remains one of the most memorable works; it marked his foray into the classical repertoire. While Nuevo Tango was a lot more intricate and experimental than tango in its early avatars, the new style unravelled the entire range of human emotion in the same manner that primitive tango did. Even after his death in 1992, Piazzolla continues to inspire classical and jazz musicians.

Tango today

Today, Martín Palmeri is one such notable composer who is breaking the conventions set by the traditional rules of tango. Born in Buenos Aires in 1956, the Argentine composer, conductor, pianist and choirmaster is known for his tango-inspired works, many of which draw from Piazzolla’s technique of Nuevo Tango. His celebrated work, Misa a Buenos Aires, follows the traditional Latin mass form, harking back to the rhythms, harmonies and melodies peculiar to the Argentine tango without diluting the sanctity of the Latin text. It spans six movements and is scored for chorus, string orchestra, bandoneon and a mezzo-soprano soloist.

The idea of the tango as an expression of primal feelings has transcended time. Not only does the form thrive in settings far removed from Argentina and Uruguay, like Japan and New York, it also continues to evolve today. When the award-winning Palmeri’s achingly spiritual tango mass is presented by the SOI Chamber Orchestra at the NCPA in November, the performance will trace the trajectories of tango to inevitably reach the depths of the listener’s soul.

The SOI Chamber Orchestra will present Misa a Buenos Aires and other works in concert on 12th November at the Prithvi Theatre & on 13th November at the Tata Theatre.

This piece was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the October 2018 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.