Truth and Fiction

ON Stage brings you edited excerpts from the NCPA Quarterly Journal, an unsurpassed literary archive that ran from 1972 to 1988 and featured authoritative and wide-ranging articles. In the second part, scholar, curator and Indophile Robert J. Del Bonta discusses the West’s understanding of India’s heritage and traditions, and the sometimes skewed portrayal of it.

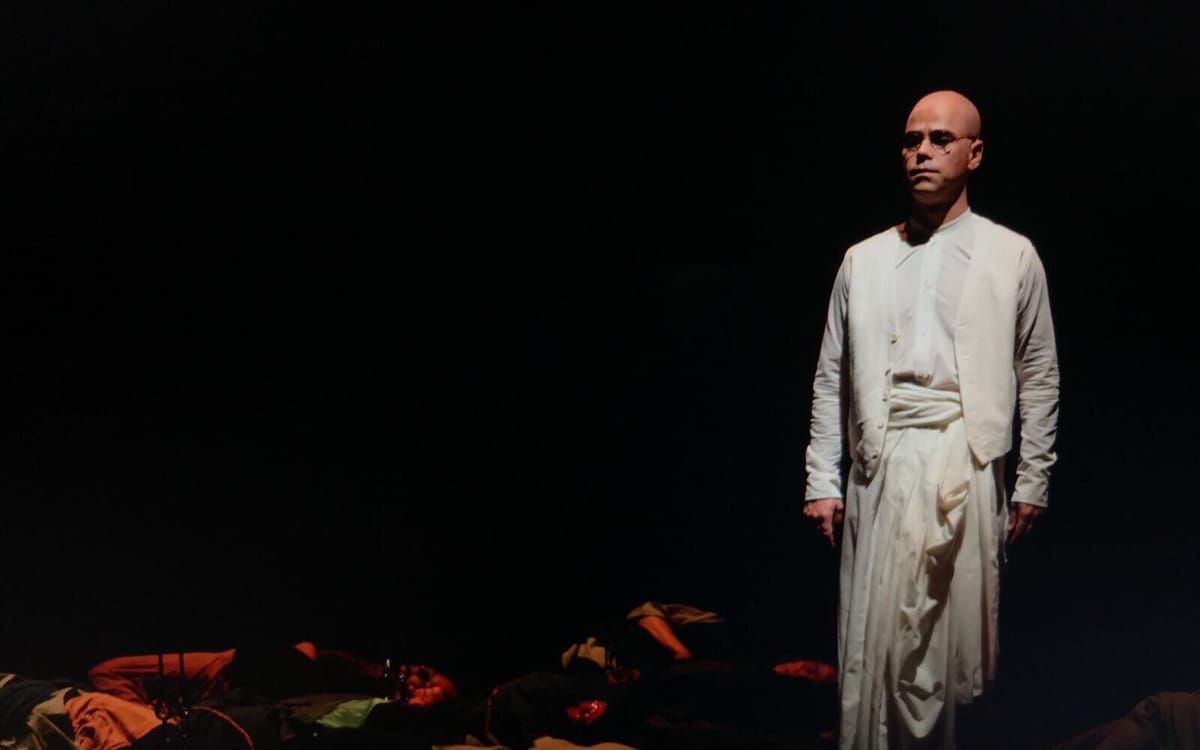

The most interesting thing for an lndophile is that few of these operas owe much to the real India. One might presume that this fact would be disappointing but many of the mistakes and oddities of the libretti illustrate the way the West has viewed India over the past few centuries, beginning with the lush tropical setting for melodrama in Adolphe Adam’s Si J’étais Roi and ending with Phillip Glass’s rather surrealistic vision of the Mahatma, set to verses of the Bhagavad Gita sung in Sanskrit in his opera, Satyagraha.

With the exception of the most recent operas concerning India, the picture of India is often lumped together with an equally hazy vision of the Islamic world. This may not seem true at first glance—considering that the plot lines of the most popular ones are consistently Hindu.

Leila is the name of the Hindu priestess in Les Pecheurs de Perles, but it is also the name of a very popular heroine in Persian literature, indeed the heroine of the opera Leyli and Medzhnun by Uzeir Abdul Husein Hajibeyov, a Persian composer from Azerbaijan. Nadir, Zurga and Nourabad are Persian as well, but they are all plopped down in a fishing village in Sri Lanka, the tropical paradise depicted in so many of the French operas about India.

After the duet “Au fond du temple saint” for tenor and baritone (often referred to as “That duet from The Pearl Fishers” on FM radio), the priestess Leila makes her entrance. Both the tenor and baritone have loved and forsaken her, but her reappearance—heavily veiled and ordered not to speak to any man—gets the drama rolling. Needless to say, the tenor and soprano sing lengthily of their love, the baritone finds out, condemns them and then saves them. The whole plot rests on the fact that the lady is veiled.

Down to perception

Most of these operas are Hindu in theme, but much of their romance owes a great deal to the picture of the veiled lady in the harem, removed from the world, and, therefore, desired by every male around—they must be beautiful if they are protected in such a fashion, after all. For an old India hand with a rather strong penchant for the Hindu world, Leila’s predicament as she sings to the great god Brahma is musically beautiful, but difficult to accept when forced into a historical setting.

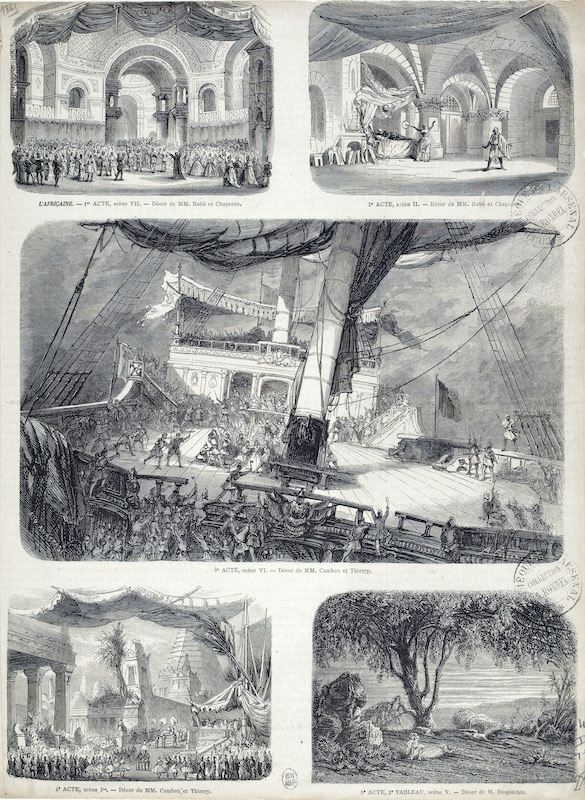

The grandest of the 19th-century French grand operas is L’Africaine, the last work of Giacomo Meyerbeer. Again, we are presented with a tropical landscape, including a deadly tree under which the Indian beauty Selika grandly inhales its perfumes in a sophisticated and melodic, if not quite believable, suicide. Her Western lover, Vasco da Gama, lends some basis of historical accuracy to the plot, but, as seen in these Indian operas, the name Selika hints of an Arabic heritage for this Hindu queen-priestess, just as the earlier protagonists of Bizet’s opera hint at Persian origins.

The plotline of L’Africaine is anticipated in part by the opera Jessonda of 1823 by Louis Spohr, based on A.M. Lemierre’s La Veuve de Malabar about the love of Tristan d’Acunha for the widow of the Maharaja of Goa. The similarities are primarily the Portuguese-Indian connection since the lovers are united after the widow is saved from death on her husband’s funeral pyre.

While at least one source suggests that Jules Massenet’s Le Roi de Lahore—his first opera written for L’Opera in Paris—was based on a story from the Mahabharata, the story suggests otherwise. Again, the names used are surprising. Timour, the name of the Central Asian conqueror (the Tamerlane of our high school English classes) is quite inappropriate for a Brahman priest. Scindia, the name of the heroine’s uncle, is an Indian name but one that’s used only by the most recent ruling family of Gwalior, many years and miles removed from Lahore during the raids of Mahmud of Ghazni in the early 11th century. Sita, the heroine, and the god lndra are the only authentic Hindu names of the lot.

My favorite Indian opera for a variety of reasons is Leo Delibe’s Lakmé, which owes much to the same interest in the exotic of the earlier French operas. There is a definite attempt to portray India in this opera, although some of it may seem wrong. We can notice these errors since we are in a more fortunate position to understand India better than 19th-century librettists.

It is often stated that the libretto of Lakmé is based on Le Manage de Loti by Pierre Loti (pseudonym of Julien Viaud), but even after a glance at this charming fictionalised travelogue, it is soon discovered that it is not about India at all and instead takes place in the South Seas. The point is that rather than saying “based on”, these accounts of the opera should read “inspired by”. Both works concern an East-West romance and on one level may suggest the non-Western siren, but both Rarahu, the primitive girl from Bora-Bora in the novel, and Lakmé, clearly the product of a sophisticated and highly moral ancient civilisation, are destroyed by their encounters with the West. The men survive. Lakmé is driven to suicide, while Rarahu takes on with any good-looking sailor before she succumbs to her malady.

For the opera buff, it is curious that another book by Pierre Loti, Madame Chrysanthème, was the inspiration for the series of works that led to Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. Although about Japan and a Japanese wife for a foreigner, Madame Chrysanthème has little to do with Puccini’s popular opera. Where Loti plays the amoral Frenchman, the operatic characters of Gerald and Pinkerton are quite different.

I am not sure if many who have visited India can completely believe the setting of Lakmé. I have yet to find the tropical garden in which Lakmé is kept by her father; I have searched for it on my travels to India and I really do hope I find such a thing amid the harsh realities of India. At the same time, the story of the love between the innocent Lakmé and the Britisher, whose call to duty leads her so quietly into suicide, is extremely moving, if not quite Indian in sentiment and content. Where in Madama Butterfly, the amoral and somewhat dense Pinkerton pushes Cio-Cio-San to her grand rite of suicide, Gerald seems less guilty. He certainly has no Sharpless to warn him of the delicate nature of the heroine; rather, he and Lakmé become the victims of the confrontation of two cultures.

Lakmé is the only opera holding the stage which deals with the English experience in India, while both Jessonda and L’Africaine deal with the Portuguese in India. It is interesting that British literature did not give rise to any opera still performed today. The only operas mentioned in the standard references are based on Thomas Moore’s Lalla Rookh from his Oriental Tales. They are Spontini’s Nurmahal of 1822 (based on his play with songs Lalla Rookh of 1821), Rubinstein’s Feramors of 1863, David’s Lalla Rookh of 1877, Lalo’s Namoura of 1882, and a few ballets. The most telling revival of an opera could be of The Englishmen in India of 1828 by Sir Henry Bishop.

In touch with reality

It is with Savitri by Gustav Holst that we find our first genuine Indian story. This falls into what is called Holst’s Indian period which includes an opera Sita of 1900-06, a cantata entitled Cloud Messenger of 1909-10, and both Hymns and Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda. Savitri truly is a tale from the Mahabharata, and Holst, his own librettist, tells it as it was written. With its small orchestra consisting of two string quartets, a contra-bass, two flutes and an English horn, the music of Savitri may not be in the same grand manner as the French operas already discussed, but it is extremely compelling. It tells the beautiful story of the outwitting of Death by Savitri, the devoted wife, and the return to life of her husband Satyavan. Rather than offer her own life to save that of her husband, as does the Western Alceste in Gluck’s opera, Savitri approaches the matter from a purely Indian point of view—she asks for her own life. When Death points out that she already has it, she instructs him in the definition of what life is to a woman: to fulfil her functions of wife and mother. In India, a husband’s death is related to the merit (karma) of his wife, and the plight of the childless widow is often extremely unpleasant. Only the land which shocked the British with its numerous suttees (satis) could present such a non-modern sentiment in so poignant a manner.

While Holst’s story comes from the ancient literature of India, as did the few operas based on Kalidasa’s Shakuntala, I have to date heard only one opera which is based on an actual event in the rich history of India, and that is Padmavati by Albert Roussel. There is also a ballet by the same title by Leo Staats from 1923.

The characters of the opera are, on the whole, accurately named. Ratan Sen is Ratan Singh, the Maharaja of Chitor, and the husband of the beautiful and the accomplished Padmavati, originally a princess from Sri Lanka and named Padmini in history. The historical uncle and cousin of Padmini, Gora and Badal respectively, are members of Ratan Sen’s staff in the opera. Ala-ud-din Khalji is presented as a Mughal, although the Mughals did not take control of India until the fall of the Delhi Sultanate in the early 16th century.

This article was originally published from the Archives section by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the November 2021 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.