There Will Always Be Stars in the Sky: The Life and Legacy of Lata Mangeshkar

It was through my mother’s voice that I discovered Lata Mangeshkar’s. My mother would often sing or hum to herself as she went about her household chores. I, a toddler and then a boy, listened with pleasure. To me, these were my mother’s songs. She then told me that some favourites, like Naina Barse Rimjhim Rimjhim and Aayega Aanewala, were sung by a diva called Lata Mangeshkar. In due course, I discovered Lata myself, and her songs kept me company down the years as I moved across countries and continents.

Lata Mangeshkar has bid adieu after a remarkable career and an equally remarkable life. But how did her story begin?

The Blossoming

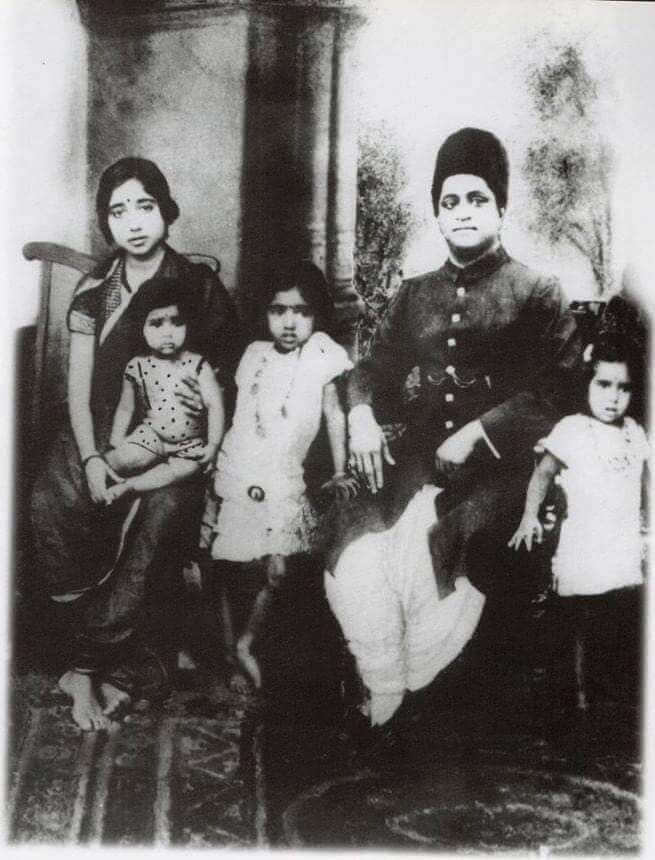

Hema, the eldest child of Deenanath and Shevanti Mangeshkar, was born on 28 September 1929 in Indore. Deenanath’s daughter from his previous marriage, Latika, had died in infancy. In her memory, Hema’s name was changed to Lata. According to an alternate version she was named after a character Latika in Deenanath’s play Bhav Bandhan. It is, of course, possible that both Hema and the character in the play were named after Deenanath’s deceased daughter.

Deenanath was a Hindustani classical vocalist and active in Marathi theatre. He scripted musical plays (Sangeet Natak) and acted in them. Lata had no formal schooling; relatives taught her to read, write and count. From the age of five, she received music lessons from her father and acted in his plays.

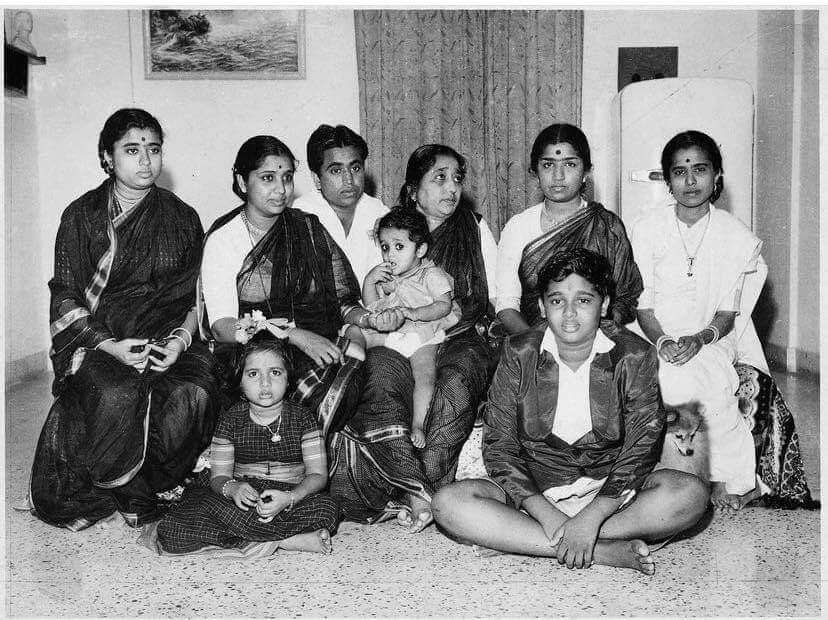

The Mangeshkars fell on hard times. When several of Deenanath’s productions flopped in a row, he wound up his theatrical company. After they lost their house in Sangli, he became an alcoholic and soon died. As the eldest child, Lata, at age 13, became the breadwinner of the family, responsible for her mother and siblings Asha, Usha, Meena, and Hridayanath. She continued this for many years until her siblings were able to establish their careers. She never married.

The Mangeshkars moved to Mumbai where “Master” Vinayak D. Karnataki, a family friend who owned a small film production company, helped Lata get minor roles in Marathi and Hindi cinema, starting with the Marathi film Pahili Mangalagaur.

“I never liked it — the makeup, the lights,” she said in an interview in 2009.

“People ordering you about, say this dialogue, say that dialogue. I felt so uncomfortable. The day I started working as a playback singer, I prayed to God: ‘No more acting in films.’”

But talent alone does not carry you onward and upward in the world. As Thomas Gray wrote: “Full many a flower is born to blush unseen, And waste its sweetness on the desert air.” Talented people need a little bit of luck as well. Lata Mangeshkar was fortunate in being in an opportune position amid changing circumstances.

The year was 1947. As India cast off the shackles of British rule, so was the Indian film industry casting off the practice of having actors sing their songs. They had begun hiring singers instead. Lata was picked to sing in a few low-key Marathi and Hindi films.

Then two episodes became turning points in her life.

Impressed by her vocal ability, music director Ghulam Haider championed her, introducing her to producers, not always successfully. Producer Sashadhar Mukherjee flatly rejected her, labelling her voice as thin and reedy. Intensely annoyed, Haider predicted: Mark my words, the day will come when producers and directors will fall at her feet and beg her to sing in their films. Her first major break was singing Haider’s composition Dil Mera Toda, Mujhe Kahin Ka Na Chhora in the film Majboor (1948). In an interview on her 84th birthday, Lata acknowledged Haider as her godfather and mentor: “Ghulam Haider was the first music director who showed complete faith in my talent.” Such was Haider’s confidence in Lata that he invited several music directors to attend the recording of Dil Mera Toda. One of them was Khemchand Prakash.

Khemchand Prakash chose Lata to sing in the film Ziddi. The following year, he picked her again to sing in the film Mahal. Its signature song was Aayega Aanewala (“He who is to come, will come”). Overnight, it would change Lata Mangeshkar from a duckling into a swan.

Mahal (“The Mansion”) was Bollywood’s first Gothic film. The story centres on a man who moves into an ancient manor, glimpses his past life, and is haunted by a beautiful woman. The first time the man sees the apparition, a pivotal moment in the story, is when Aayega Aanewala plays. The opening lines set the tone for the haunting as well as for Lata’s imminent arrival on the music scene:

खामोश है ज़माना, चुप-चाप हैं सितारे

आराम से है दुनिया, बेकल है दिल के मारे

ऐसे में कोई आहट, इस तरह आ रही है

जैसे कि चल रहा है, मन में कोई हमारे

या दिल धड़क रहा है, इक आस के सहारे

Quiet are the times, mute are the stars

Though the world is at rest, lovers are restless

Hark! In the stillness, footsteps approach

As if someone is passing through my very soul.

Or is it only my heart beating?

German cinematographer Josef Wirsching filmed the sequences in black and white: the moon playing hide and seek with the clouds, the apparition playing hide and seek with the man. And then there was Lata Mangeshkar. Even though it was early in her career, the agility in her singing was an indication of the coloratura soprano that she would become. Mahal was a box office success.

Those days, playback singers were regarded as people who sang for their supper rather than artists in their own right. They performed, were paid their wages, and dismissed. When HMV released the gramophone recording of Aayega Aanewala, the singing was credited to Kamini (the name of the character played by actress Madhubala, who lip-synced the song onscreen). Aayega Aanewala was a smash hit on radio. Not only were there hundreds of requests to replay it, but listeners demanded to know the singer’s identity. Radio stations then revealed that “Kamini” was Lata Mangeshkar. She became a household name.

From this point on, playback singers were credited on record labels and onscreen, starting with Barsaat, and followed by Andaz and Badi Behn. Lata’s big regret was that Khemchand Prakash died two months before Mahal was released and did not see her meteoric rise on the crest of his music. She who was to come, had come. And having arrived, she never looked back.

The Reign

But the early years of her career were anything but easy. Playback singers recorded their songs on the film sets, often early in the morning before the day’s shoot began or at night after it was over. The sets were cramped, hot, and dusty, and when the noisy fans were turned off, the rebounding heat made creative work difficult.

Eventually recording studios came along, and with them, a different kind of schedule. In the 2009 biography, Lata Mangeshkar in Her Own Voice, written by Nasreen Munni Kabir, Lata reminisced, “I recorded two songs in the morning, two in the afternoon, two in the evening and two at night. I left home in the morning and got back at 3 a.m. the next day and that’s when I ate. After three hours of sleep, I would wake up at six, get dressed, catch the train and travel from one recording studio to another.” Producers sometimes forced her to work without pay, slipping her wages into their pockets.

Lata never rested on her laurels, no matter how many awards or accolades she got. The actress Waheeda Rehman, Lata’s good friend, recalled,

“Her voice had magic but behind that magic was a lot of hard work and determination. She would rehearse and rehearse so much.”

This practice continued even when Lata was at the crest of her career. Remembering their many shows in the United States, Waheeda said, “She used to sit backstage and keep doing her riyaaz till she perfected her sur before going on stage and singing.”

Like Julie Andrews, Whitney Houston, and Freddie Mercury, Lata Mangeshkar had an impressive four-octave range. What made Lata stand out as a playback singer was that she sang in character. She understood the distinction between being able to sing and knowing how to sing. Other singers may have been content giving a rendition after fitting the tune to the lyrics, but not Lata. She tailored her voice to what would be shown on the screen. What is the feeling that lies at the heart of this song? How might an actress portray it onscreen in the context of the story? How can I make my voice reflect those emotions in a way that best reflects what people see on the screen? Thus we have the upbeat Aaj Phir Jeene Ki Tamanna Hai (“Today, I once again desire to live”) from the film ‘Guide,’ and the quiet yet solid affirmation of love Tu Jahan Jahan Chalega (“No Matter Where You Go”) from ‘Mera Saaya.’

In a career that spanned an astonishing seven decades, Lata Mangeshkar recorded countless songs in over two dozen Indian and foreign languages. When asked the exact number, she shrugged and said she never kept a log of her recordings. She occasionally did a double-take when somebody forwarded one of her songs to her on WhatsApp: “Arrey, yeh maine kab gāyā!” (Goodness, when did I sing this?)

Her memorable songs include Kahin Deep Jale Kahin Dil (Bees Saal Baad), Aajaa Re Pardesi (Madhumati), Pyaar Kiya To Darna Kya (Mughal-E-Azam), Chalte Chalte (Pakeezah), Rasik Balma (Chori Chori), O Sajna (Parakh), Allah Tero Naam Ishwar Tero Naam (Hum Dono), and O Paalanhaare (Lagaan). The songs on several lists titled ‘Lata’s Greatest Songs’ vary greatly, for the tastes of compilers are different, but all the listed songs are unforgettable. Actresses across generations have lip-synced her songs, from Meena Kumari and Nargis to Sharmila Tagore and Preity Zinta. Nutan and her sister Tanuja and then, years later, Tanuja’s daughter Kajol have all benefited from Lata Mangeshkar’s voice in their films.

Lata sang in several Indian languages as well, among them Bengali, Marathi, Kannada, Gujarati, Assamese, Tamil, and Malayalam. Videos of two such songs, one in Assamese and the other in Tamil, follow below.

Jonakare Rati, in Assamese, composed by Bhupen Hazarika, from the film Era Batar Sur

Her pronunciation in any language was impeccable, including in songs sung in a fast tempo, such as Valai Osai, presented in the video below. “The Tamil language was really difficult for me to handle,” she said in an interview. “I would note down all the lines in English and then master their pronunciation, as they are very particular about the accent and diction.” She sometimes transcribed the lines in Devnagari script.

Valai Osai, Tamil song from the film Sathya, composed by Ilayaraja. Duet: Lata Mangeshkar & S.P. Balasubrahmanyam

English was not a language Lata Mangeshkar sang in, but at a fundraising event in Toronto in June 1985 for the charity United Way, Canadian singer Anne Murray requested Lata to sing one of her popular songs, You Needed Me. Lata obliged, though she just had a few hours to learn the song. The compère cheekily introduced it as a presentation from “Anne Mangesh.”

Lata Mangeshkar sings Anne Murray’s “You Needed Me,” Toronto, Canada, 1985

Foreign languages in which she sang included Dutch, Malay, Russian and Swahili. They were not original songs but covers of popular songs in those languages. Lata found Russian the toughest language to sing, so more is the pity that there is no recording of her feat. The Russians prohibited recordings of her concerts. Here is a recording of her singing the Malay song Sekuntum Mawar Merah (A Single Red Rose):

Lata Mangeshkar sings Sekuntum Mawar Mera in Malay Bhasa (1994)

Perhaps the most famous Swahili love song of all time is Malaika (“Angel,” slang in Swahili for a beautiful woman), so famous that both Tanzania and Kenya claim it as theirs. It is the lament of a poor young man who offers his heart to his angel but is crushed by the bride price (dowry) that he is required to shell out. The song became famous worldwide when it was performed by the South African star Miriam Makeba, followed by covers from Harry Belafonte, Pete Seeger, Boney M, and Angélique Kidjo. Here is Lata Mangeshkar’s rendition:

Swahili love song Malaika (Angel), sung by Lata Mangeshkar in Nairobi, Kenya, 1971

Throughout her life, Lata sang in concerts to raise money for charities. And she continued to press for the betterment of artists in the film industry. She refused to perform at the annual Filmfare Awards ceremonies until they created an award category to recognize playback singers, which they did in 1959. She was the first female singer to demand better pay on par with male singers. Her call for a share of royalties in addition to the flat fee paid per song caused a rift between her and Mohammed Rafi, who thought differently. The two refused to sing together; until the time they reconciled, Kishore Kumar became her main partner in duets. Those days, the prestigious auditoria were reserved for classical music concerts, with film music shows relegated to community halls. Lata Mangeshkar fought to bring film music to mainstream venues ― and won.

Primary among her activities outside the film industry that remain in people’s memories is her rendition of the song Ae, Mere Watan ke Logo (Oh, My Fellow Citizens) at the Republic Day function in 1963 in the presence of President S. Radhakrishnan and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. The disastrous Sino-Indian war had concluded a couple of months back leaving the nation in a sombre mood. The song was a tribute to the soldiers fallen in battle in defence of the country. Nehru was reduced to tears and made no attempt to hide it.

Lata Mangeshkar’s rendition of Ae, Mere Watan Ke Logo, Ramlila Maidan, Republic Day 1963. Lyrics by Kavi Pradeep and music by C. Ramachandra

Lata made an album of Meera Bhajans with music by her brother Hridayanath, and another album Shraddhanjali, where she gives her interpretations of a selection of songs of other great singers, among them K.L. Saigal, Pankaj Mallick, Geeta Dutt, Kishore Kumar, Mohammed Rafi, Zohra Bai, and Mukesh.

One Life, Many Destinations

Entertainers and public figures are best known for what made them famous, but they are people like you and me, each with their individual passions and dislikes, their habits, hobbies, and foibles. Lata Mangeshkar was no different. Her personality was multifaceted and surprisingly unpredictable, and her life was rich. Her memorable song Ajeeb Dastaan Hai Yeh (A Strange Story, This!) could, with a little imagination, be applied to her own life.

अजीब दास्तां है ये

कहाँ शुरू कहाँ खतम

ये मंज़िलें है कौन सी

न वो समझ सके न हम

A strange story, this!

Where does it begin?

Where does it end?

What sort of destinations are these?

He cannot comprehend this –

Neither can we.

Lata Mangeshkar sings about the story that we call “Life” | Outdoor concert, Hyderabad, 2002

Does a story commence at birth and wind up at death? Do not events before birth shape a life? Is there not a life after death? What about the landmarks along life’s journey? They are usually thought of in terms of graduation from school or college, landing a job and a spouse, becoming a parent and so on. But, as the song questions, what exactly are destinations? The “destinations” of each segment of Lata Mangeshkar’s story were many; they included cars, cameras, chocolates, cooking, cinema, and cricket.

Cars and cameras made her day. When she became successful as a singer, she treated herself to a Chevrolet. Later she owned a Hillman, a Buick, a Chrysler, and a Mercedes, the last gifted to her in appreciation by filmmaker Yash Chopra. Photography was a passion. She owned several professional-level cameras. In her early years, she never went anywhere without her trusty Rolleiflex. Her photographs were good enough to be exhibited, and for a time she considered professional photography as a career to fall back on if she did not make it as a singer. The new trends in photography brought her misgivings:

“It’s a pity that the art of clicking pictures has been replaced by digital photography. People now take all their pictures on their phone. The sheer joy of capturing images through the lens of an old-fashioned camera is lost.”

Waheeda Rehman capitalised on Lata Mangeshkar’s fondness for chocolates for a good cause. Waheeda wanted Lata in the shows she was organising in Bangladesh after the 1971 war. They had done shows together in America ― but this time, Lata turned her down. Waheeda knew Lata’s tastes (chocolates, kebabs, biryani) and plied her with chocolates until Lata changed her mind. On the Bangladesh tour, Waheeda found herself in a hotel room without water supply, and used Lata’s bathroom. But halfway through her bath, the water stopped and Waheeda was left decorated with soap. Lata scouted for a water source and personally hauled buckets of water to her room to help out her friend.

India is a cricket crazy country where the thwack of leather against willow is a religious ceremony, and Lata Mangeshkar was an ardent devotee. Bollywood had to reconcile with her unavailability for recording sessions when a test match was on. The proud owner of a signed photograph of Don Bradman, she exulted when India dethroned the formidable West Indies to win the cricket World Cup in 1983. But she was taken aback when the Board for Cricket Control in India offered each team member Rs 25,000, a sum she considered below par for what they had achieved. She held a fundraiser concert and raised the amount to Rs 1 lakh per player, a considerable sum for that time. A grateful BCCI then offered the Mangeshkar family two complimentary tickets for every international cricket match that India played.

Lata Mangeshkar’s London house was close to Lord’s; she often invited Indian cricketers for a meal. Cricketer Dilip Vengsarkar has fond recollections of the sumptuous luncheon she hosted in his honour after his third century at Lord’s. Vengsarkar and his team mates, who had only thought of her as a singer, discovered that she was a fabulous cook: Kolhapuri style mutton as fiery as a Kapil Dev bouncer, followed by a mellow full toss, carrot halwa.

She listened to Western classical music; her favourite composers were Chopin, Beethoven and Mozart. In contemporary Western music, artists who held her ear included Nat King Cole, Barbra Streisand, The Beatles, and Harry Belafonte. And Marlene Dietrich, whose stage performance she attended.

She was drawn to James Bond films, at least the early ones with Sean Connery and Roger Moore. She also loved the theatre of Ingmar Bergman, which is as far removed from James Bond as is possible. She loved Hollywood musicals, admitting that she had watched The King and I at least 15 times.

As Lata Mangeshkar listened to that film’s catchy songs like I Whistle A Happy Tune, Getting to Know You, and Shall We Dance? I wonder whether she was aware of Margaret “Marni” Nixon, the playback singer who sang for Deborah Kerr. Hollywood had retained the modus operandi of the singing star; actors singing their own songs. Most Hollywood movies are not musicals and in the few that were, producers chose actors with a singing voice. But occasionally an actor was cast who could not carry a tune but was suited for the role in every other way, and a playback singer was employed. For a long time, this was not public knowledge. Marni Nixon sang for several stars, including Marilyn Monroe in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Natalie Woods in West Side Story, and Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady, without receiving credit for any of them. She was even threatened by Twentieth-Century Fox over The King and I: “…if anybody ever knows that you did any part of the dubbing for Deborah Kerr, we’ll see to it that you don’t work in town again.” The film’s soundtrack album sold in the hundreds of thousands, but all Marni Nixon received was a measly $420 ― and no credits.

All of this took place two decades after Indian playback singers got credits and better pay, thanks to Lata Mangeshkar’s advocacy following the success of Mahal. Lata’s push for the betterment of playback singers in India’s film industry cannot and should not be overlooked or discounted.

In 1974, Lata Mangeshkar became the second Indian (the first was Pandit Ravi Shankar, 1969) to perform at the Royal Albert Hall, London. But she was daunted about touring America, and appreciated her colleague Mukesh for not only talking her into it, but also accompanying her and performing onstage together. Lata was famous among the Indian diaspora but Americans in general still thought of Indian music as synonymous with Ravi Shankar and Hindustani classical music. Her concerts at venues such as Oakland Auditorium (San Francisco), Shrine Auditorium (Los Angeles), and Madison Square Garden (New York) helped mainstream America become aware of India’s film music.

When in America on holiday, a favourite destination was its “sin city,” Las Vegas. Mukesh first took her there and she was hooked. Indians visiting the casinos were taken aback to spot her working the slot machines with abandon without batting an eyelid even after losing heavily. One said he finally understood the meaning of “the shock of my life” after his image of Lata, that of the demure and conservative lady next door, was blown into a thousand itty-bitty pieces.

She never played roulette or cards because she didn’t know how, she said, but she thought nothing of spending an entire night at the slot machines. It was inevitable that the Indian news media would find out and make a splash about it. How Lata took it at the time is not clear – she was a notoriously private person – but in later years, the whole thing amused her. “They even called me a gambler,” she chortled.

Lata Mangeshkar was a Sherlock Holmes fan, and owned every book by Arthur Conan Doyle which featured the detective. And she was an avid dog lover. At one point, her household included nine dogs. She regularly posted pictures of her dogs on Instagram, gushing over them and leaving sweet messages for them.

When one is a celebrity, politicians want to rub shoulders with you. Lata maintained cordial relations with politicians across all parties. But in the current polarized political atmosphere prevalent in India, eyebrows shot up over her support of Prime Minister Modi. It raised smiles or hackles amongst people depending on their political leaning.

However, the Mangeshkars have been longstanding admirers of Hindu ideologue V. D. Savarkar. Savarkar wrote a musical play Sanyastha Khadag for Deenanath Mangeshkar’s company. And Savarkar regularly hosted dinners at which Deenanath was a guest. Deenanath started taking Lata along, brushing aside his wife’s objections: “She needs to know right now what Savarkar is doing and why it’s so necessary.” Lata would address Savarkar as ‘Tatya” (a term of respect for an older man).

Lata regularly acknowledged Savarkar’s birth and death anniversaries through tweets. She once posted on Twitter the audio of a song from Savarkar’s play which her father had produced. Her brother Hridayanath set many of Savarkar’s poems to music, and she has sung a few of those songs. But Lata, it must be said, did not become a crusading activist for any political ideology in the manner of Jane Fonda and Susan Sarandon.

She was nominated to the Rajya Sabha but did not enjoy her tenure one whit. During those six years, she never gave a speech and asked only one question: why was there an increase in the derailment of trains, what was the cost to Indian Railways, and pray, what the government was doing about it? She always maintained that she was a misfit in Parliament and politics. She never touched a rupee of the payments she was entitled to as a parliamentarian, returning all the cheques.

Adieu

Lag Jaa Gale, a song from the 1964 mystery thriller Woh Kaun Thi? (Who Was She?), regularly features in lists of the top Lata Mangeshkar songs. If Ajeeb Dastaan Hai was a reflection on life as a conundrum, Lag Jaa Gale is a meditation on life’s transient nature. Raja Mehdi Ali Khan’s lyrics are open to interpretation. The context in the film is about the parting of lovers, but it can just as easily be construed as the ultimate parting: death. And the Hindi phrase ‘ho na ho’ injects an uncertainty and ambiguity that is hard to capture in translation.

The actor Irrfan Khan, who passed away in 2020 from cancer, frequently played this song during his last days. And it is a fitting requiem for Lata Mangeshkar herself.

लग जा गले कि फिर ये हसीं रात हो न हो

शायद फिर इस जनम में मुलाक़ात हो न हो

हमको मिली हैं आज ये घड़ियाँ नसीब से

जी भर के देख लीजिये हमको करीब से

फिर आपके नसीब में ये बात हो न हो

पास आइये कि हम नहीं आएंगे बार-बार

बाहें गले में डाल के हम रो लें ज़ार-ज़ार

आँखों से फिर ये प्यार की बरसात हो न हो

शायद फिर इस जनम में मुलाक़ात हो न हो

Lag jaa gale ke phir yeh haseen raat ho na ho

Shaayad phir is janam mey mulaaqaat ho na ho

Hum ko mile hai aaj yeh ghadiyaan naseeb se

Jee bhar ke dekh leejiye hum ko qareeb se

Phir aap ke naseeb mey yeh baat ho na ho

Paas aayie ke hum nahin aayenge baar baar

Baahein gale mein daal ke hum ro le zaar zaar

Aankon se phir yeh pyaar ki barsaath ho na ho

Lag jaa gale ke phir yeh haseen raat ho na ho

Embrace me, for we may not enjoy such an enchanting evening again

Perhaps we might never again meet in this lifetime.

Fate has granted us these few moments.

Draw close, adore me with your eyes as much as you wish

For fate may not offer us such an opportunity again.

Come closer, for I might not return to you time and time again.

Let me wrap my arms around you and weep long,

My eyes may never shed such a shower of love again.

So embrace me, for such an enchanting evening

May never come our way again.

Lata Mangeshkar sings Lag Jaa Gale for the BBC (1979)

Lata Mangeshkar was a star who sprinkled her stardust on all the songs that she sang, converting them into little stars. Now she is gone, but she has ensured that there will always be stars in the sky,