The World’s Oldest Known Musical Notation

Discover the world’s oldest known musical notation: the Hurrian Hymn from Ugarit, dating to 1400 BCE. This ancient melody reveals how early societies preserved music, blending ritual, devotion, and artistry into timeless sound.

Music is often described as the universal language, a form of expression that transcends geography and culture. Yet unlike spoken languages, which leave behind scripts, alphabets, and inscriptions, the history of music is far harder to trace. For centuries, music existed orally: passed from teacher to pupil, community to community. What, then, is the earliest example of music fixed in writing—our first glimpse into how ancient people thought about melody, rhythm, and sound?

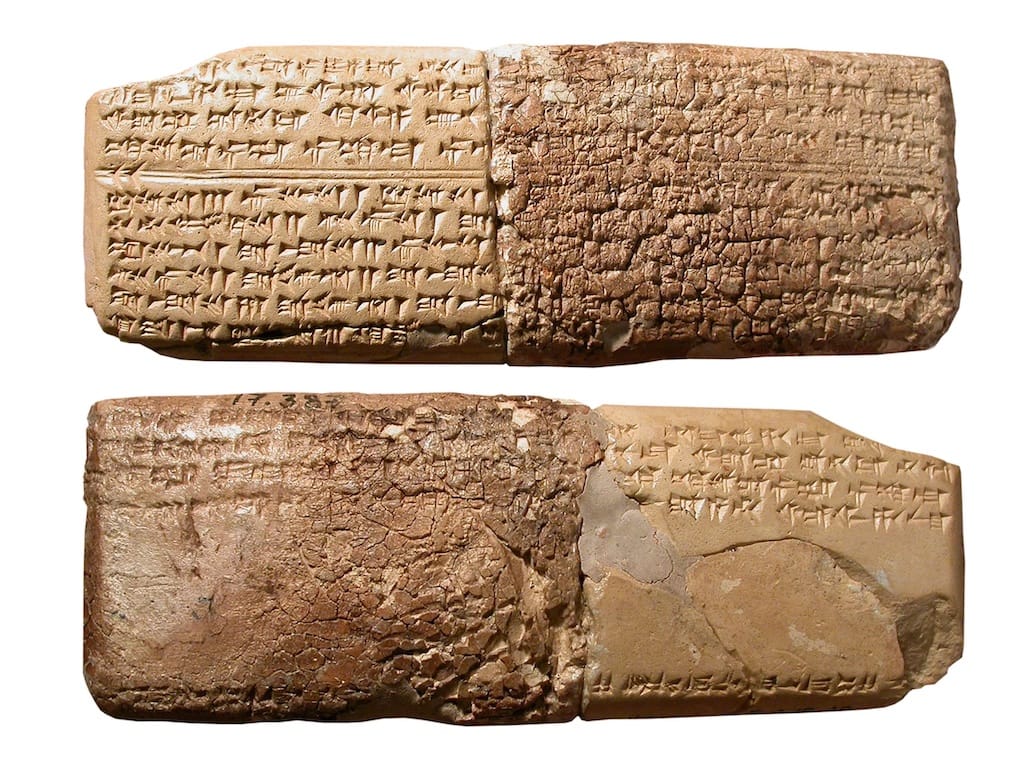

The answer lies in the dusty remains of ancient Mesopotamia, where archaeologists unearthed clay tablets inscribed with the earliest known musical notation. These fragile artefacts, dating back more than three thousand years, not only reveal the sophistication of ancient musical practice but also offer a poignant connection across millennia: the knowledge that our ancestors, too, sought to preserve their music for posterity.

Discovery at Ugarit

The most famous of these early notations was discovered in the 1950s at Ugarit, an ancient city on the Mediterranean coast of modern-day Syria. Among a cache of clay tablets written in cuneiform, archaeologists found one bearing a hymn with accompanying instructions for musical performance. Scholars date this tablet to around 1400 BCE, making it the oldest known example of written music that can be reconstructed with some confidence.

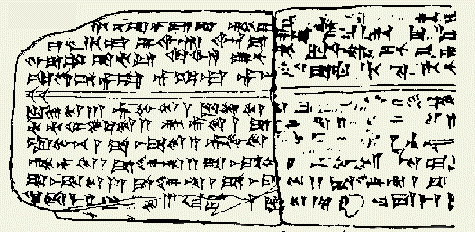

The piece is known today as the “Hurrian Hymn No. 6.” It is dedicated to Nikkal, the goddess of orchards, and written in the Hurrian language. Alongside the lyrics, the tablet includes a form of musical notation that indicates intervals, scales, and performance directions. Though incomplete and difficult to interpret, it is a remarkable attempt to capture sound in a written system.

How Did the Notation Work?

Unlike modern Western notation, which uses staves, notes, and rhythms, the Hurrian system was based on tuning instructions for a type of lyre. The symbols on the tablet describe string names, intervals, and methods for creating melodies within a particular tuning scheme.

Musicologists have debated for decades how exactly to translate these instructions. Some interpret them as a set of performance guidelines rather than a fixed score, while others have reconstructed them into playable melodies. Several modern recordings of the hymn exist, each slightly different, yet all hauntingly beautiful in their simplicity and modal character.

What unites these interpretations is the insight they provide: even in the Late Bronze Age, musicians had developed structured systems for tuning, scale construction, and composition. Far from being a primitive art, music was already a sophisticated craft deeply embedded in ritual and culture.

Music as Ritual and Devotion

The Hurrian Hymns were not casual songs for entertainment; they carried spiritual significance. Hymn No. 6, for example, invokes the favour of a goddess, suggesting a role in religious ceremonies. Music in ancient Mesopotamia was closely tied to worship, healing, and communal identity.

By inscribing this hymn into clay, the ancient scribes ensured that the melody could be remembered and repeated with fidelity, even if oral transmission faltered. This act underscores a universal human impulse: the desire to preserve sacred and artistic traditions across generations.

The Broader Context of Ancient Music

The Ugarit discovery is not the only evidence of early notation. Other Mesopotamian tablets, some dating as far back as 2000 BCE, contain lists of string tunings and scales. These texts, while not full compositions, demonstrate that musicians had a theoretical framework for their art.

Elsewhere, ancient Egypt and Greece also experimented with musical notation. The Greeks developed systems using letters to represent pitches, and surviving examples—such as the Seikilos epitaph from the first century CE—show a clearer connection to the music we recognise today. Yet it is the Hurrian Hymn from Ugarit that remains the earliest piece scholars have been able to reconstruct into a coherent melody.

Modern Reconstructions

Since its discovery, the Hurrian Hymn has been painstakingly studied and reimagined by musicians and scholars alike. Each reconstruction represents a careful negotiation between philology, musicology, and creativity.

For example, Dr. Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, an American Assyriologist, produced one of the first playable versions in the 1970s, transcribing the notation into Western musical equivalents. Later scholars such as Marcelle Duchesne-Guillemin and Richard Dumbrill offered alternative interpretations, each emphasising different aspects of the tablet’s instructions.

Contemporary ensembles have recorded the hymn using replicas of ancient lyres, giving listeners an evocative taste of what Bronze Age music may have sounded like. These recordings, often spare and modal, highlight the universality of music: even though the culture and language are remote, the melodies resonate with modern ears.

Why It Matters

The significance of the world’s oldest musical notation is not merely historical curiosity. It challenges assumptions about ancient societies, demonstrating their intellectual and artistic sophistication. It also bridges the gap between past and present, reminding us that the impulse to create and preserve music is as old as civilisation itself.

Moreover, the hymn stands as a symbol of continuity. While the specifics of notation and performance may differ across cultures, the act of encoding music in a durable medium reflects a common desire: to make ephemeral sound permanent, to leave behind traces of song for generations to come.

From Clay Tablets to Digital Scores

The journey from Ugarit’s clay tablets to modern sheet music is a testament to human ingenuity. Today, composers can not only notate music with precision but also preserve it digitally, accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Yet at its core, the impulse remains the same as that of the Hurrian scribes: to fix sound in symbols, to share music beyond the moment of its creation.

It is humbling to think that our notated traditions—symphonies, operas, jazz charts, film scores—owe their lineage in part to these ancient pioneers. Without their first attempts at encoding music, the written preservation of sound might have taken a very different path.