The ‘Visual’ Epidemic: A boon or bane for musicians?

Cafés with a beautiful ambiance are an important part of my existence as a student. Not because it serves good coffee (partly) but because it has a visual appeal to it. A perfectly proportionate coffee cup in my hand gives me immense satisfaction. And I know there are many like me. There is a very important need for everything to be visually appealing. From Instagram feeds filled with charcoal coloured food to colour therapy: Image is important. This is what our generation thrives on. It is almost as if we’ve gone back to the ‘Age of Enlightenment’ where we adore symmetrical satisfaction: only this time it involves our vision more than anything else.

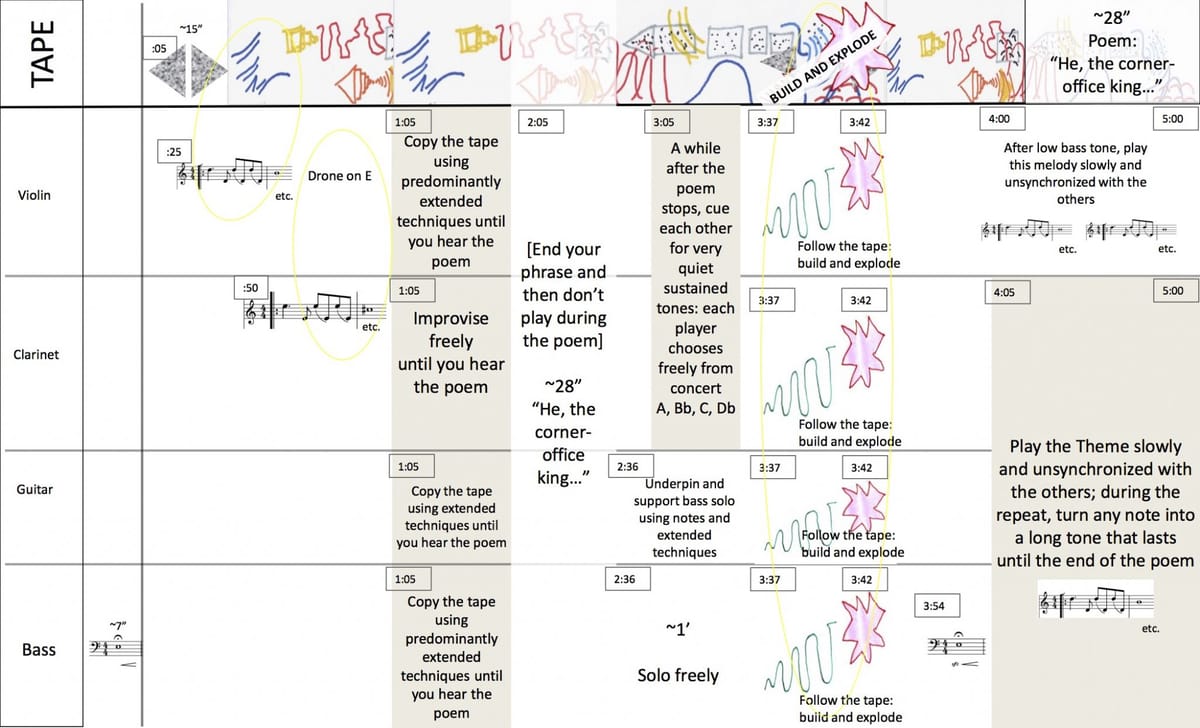

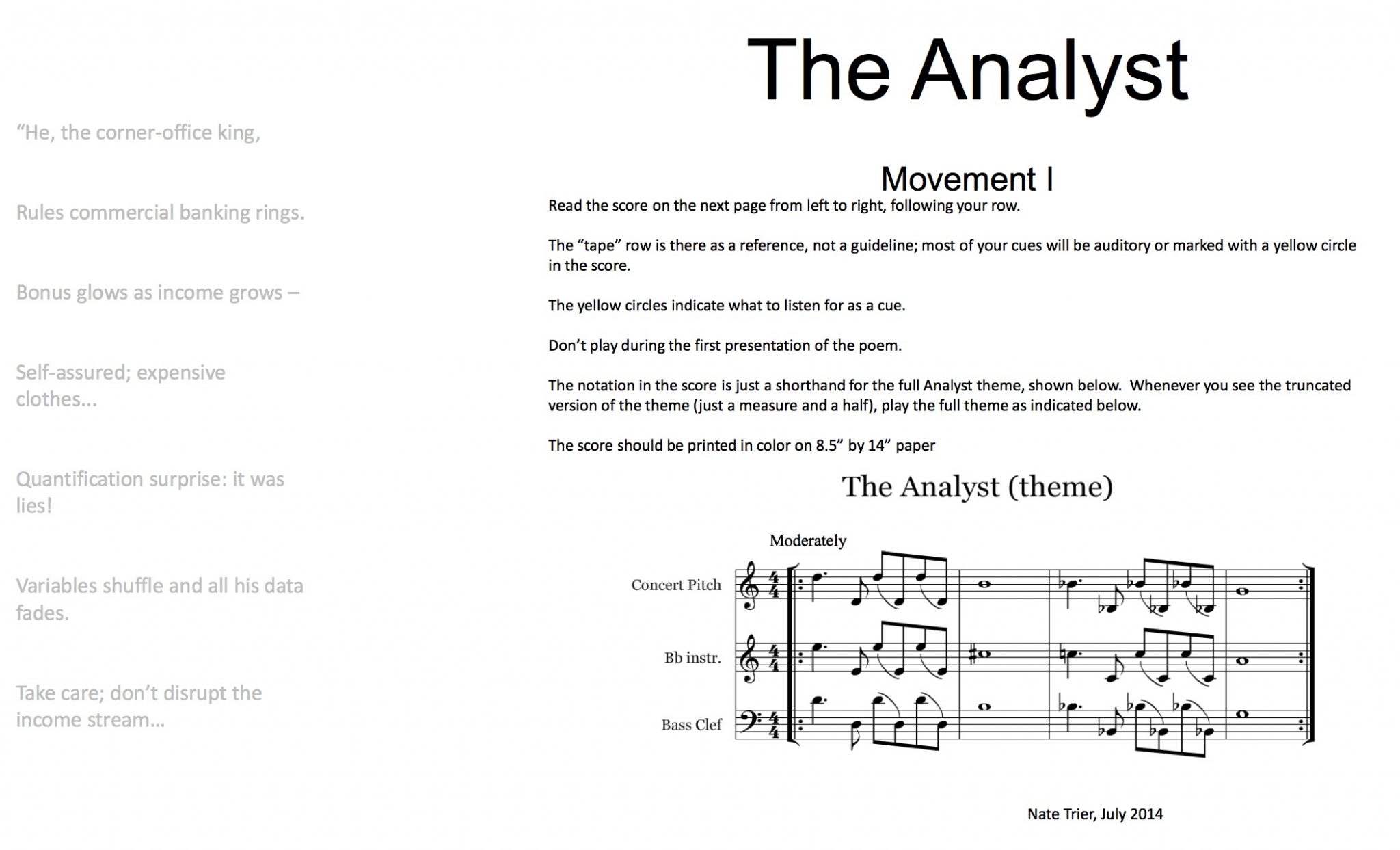

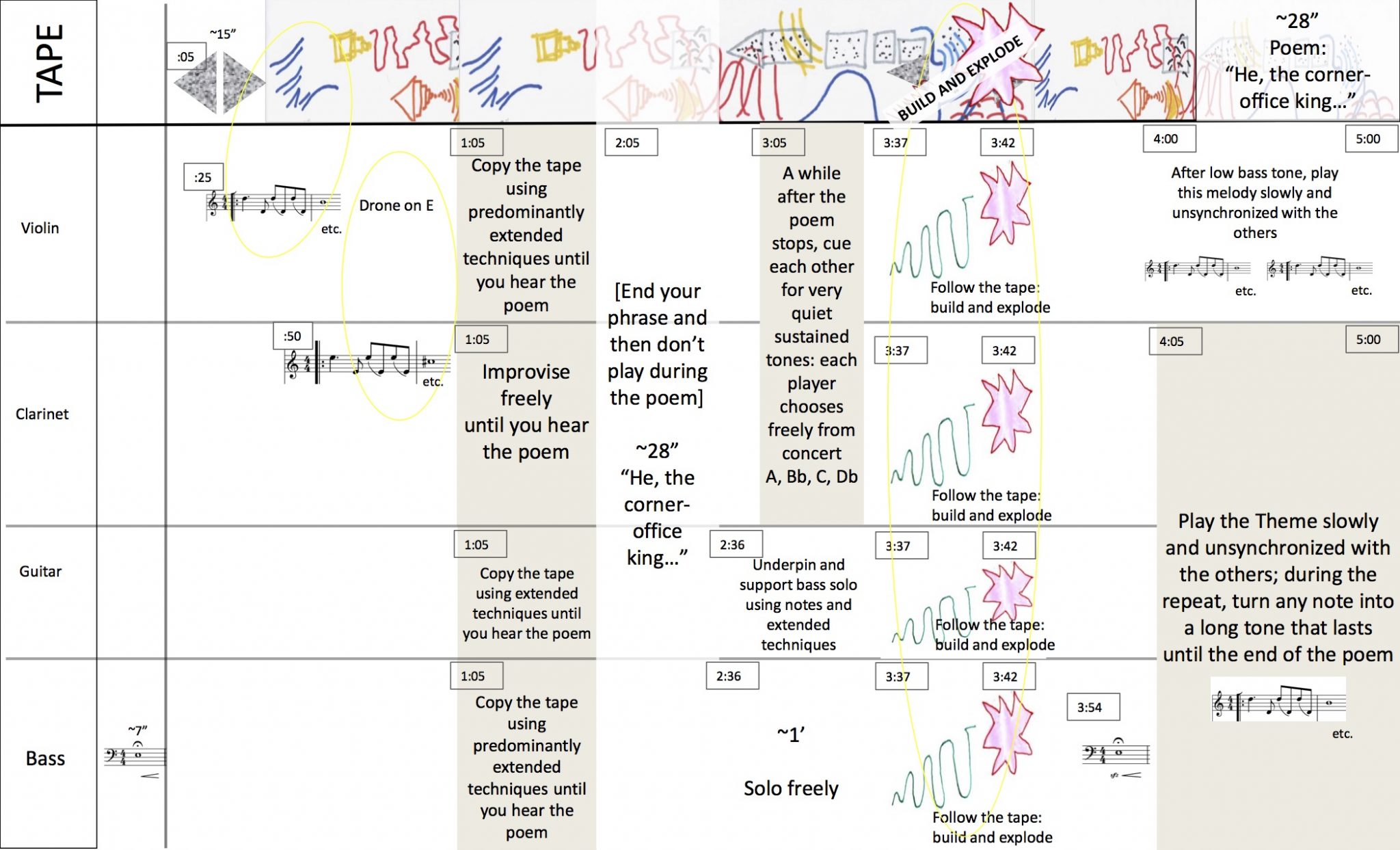

And as a musician, the right image is extremely important for my career. Being visual and actively posting good videos and pictures on social media and YouTube has become an essential form of my musical existence. Even our words are catered to the visual. We do not use famous as much as ‘getting noticed’. Being a part of the ‘visual epidemic’ definitely has its perks. In our quest for the visual, new composers have become more detailed and accurate on what they exactly want from their performers. Take, for example, Nate Trier’s “The Analyst” written in July 2014, whose music score looks something like this:

It is unique, extremely detailed and ambitious in its own creative way!

In this potpourri, however, we see what is in front of us as the ultimate truth and this works against us musicians. As classical musicians, we do not have the actual composers working with us. Hence, we take the score as the ultimate truth rather than a starting point for artistic musicianship and liberty. Recently, I heard gorgeous mezzo-soprano Rita Gorr sing J’ai Perdu mon Eurydice from C.W. Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice. Having heard many recordings of this piece previously, it was refreshing to hear an ever-changing tempo in collusion with the given text. It was delightful to hear the singer as a soloist rather than just a member of an ensemble as is the norm these days. The text conducted the tempo, the dynamics and the movement of the orchestra. This is what I find lacking in today’s music. In our adamance to get an audio replica of what is written on the score, we lose our artistic identity and our work becomes prosaic and dull.

Why are musicians trapped in a piece of paper?

I guess this all dates back to mid-20th Century. I can only speak for myself as a singer. I remember an interview where Maria Callas stresses on the score as the ‘ultimate’ guide to interpretation. She insists that if the singer ever needs help in understanding her character, all she needs to do is look at what the composer has said and sing exactly what’s written.

But what if, we have reached a stage where we take every marking too literally? Especially in terms of music of the 16th and 17th Century where a Larghetto suddenly becomes too rigid. This completely changes the composer’s interpretation. My professor once said that in Handel or Bach’s time, tempo definitions were never meant to be taken too seriously. It was up to the singer. And yet here we are!

It is time that we change norms for good. Our interpretations must be our reflection and interpretation of the character. Only then can we make our music ubiquitous and engaging to the ear! Only then, can we performers mark ourselves in today’s Classical Music Scene!