The Velvet Revolution of Claude Debussy

How a reclusive Frenchman created some of the most radical, beautiful music of the modern era.

Claude Debussy died a century ago, but his music has not grown old. Bound only lightly to the past, it floats in time. As it coalesces, bar by bar, it appears to be improvising itself into being—which is the effect Debussy wanted. After a rehearsal of his orchestral suite “Images,” he said, with satisfaction, “This has the air of not having been written down.” In a conversation with one of his former teachers, he declared, “There is no theory. You merely have to listen. Pleasure is the law.”

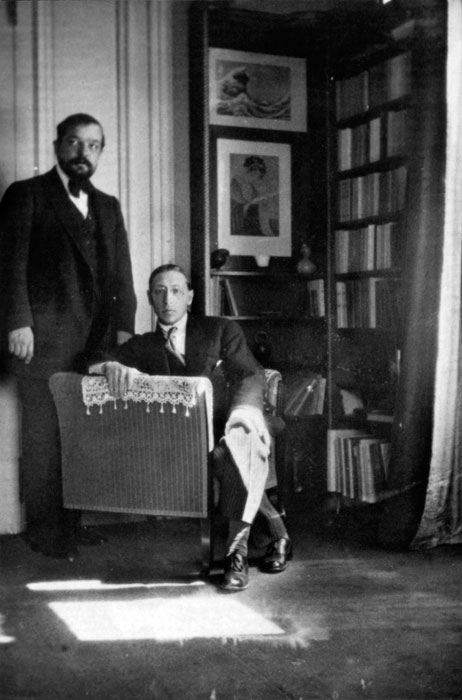

To mark the centenary of Debussy’s death, which fell in March (2018), two handsome boxed sets of his complete works have been issued. They befit a man who treasured pretty things. One, from the Deutsche Grammophon label, is decorated with Jacques-Émile Blanche’s portrait of the composer, in which he assumes an aristocratic, lapel-grasping pose. The other, from Warner Classics, displays Hokusai’s woodblock print “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa,” which, at Debussy’s request, was reproduced on the cover of one of his most celebrated scores, “La Mer.” Physical recordings are no longer a fashionable way of listening to music, but you will probably get closer to Debussy if you shut down the Internet and give yourself wholly to his world. The D.G. set has the libretto of his only finished opera, “Pelléas et Mélisande,” and the texts of his large output of songs—necessary resources in approaching an acutely literary composer whom Stéphane Mallarmé and Marcel Proust recognized as an equal.

It is best to start where Pierre Boulez said modern music was born: with the ethereal first notes of the orchestral tone poem “Prelude to ‘The Afternoon of a Faun.’” Debussy wrote it between 1892 and 1894, in response to the famous poem by Mallarmé. The score begins with what looks like an uncertain doodle on the part of the composer. A solo flute slithers down from C-sharp to G-natural, then slithers back up; the same figure recurs; then there is a songful turn around the notes of the E-major triad. Yet, in the fourth bar, when more instruments enter—two oboes, two clarinets, a horn, and a rippling harp—they ignore the flute’s offering of E. Instead, they recline into a lovely chord of nowhere, a half-diminished seventh of the type that Wagner placed at the outset of “Tristan und Isolde.” This leads to a lush dominant seventh on B-flat, which ought to resolve to E-flat, but doesn’t. Harmonies distant from one another intermingle in an open space. Most striking is the presence of silence. The B-flat harmonies are framed by bar-long voids. This is sound in repose, listening to its own echo.

Debussy accomplished something that happens very rarely, and not in every lifetime: he brought a new kind of beauty into the world. In 1894, when “Faun” was first performed, its language was startling but not shocking: it caused no scandal, and was accepted by the public almost at once. Debussy engineered a velvet revolution, overturning the extant order without upheaval. His influence proved to be vast, not only for successive waves of twentieth-century modernists but also in jazz, in popular song, and in Hollywood. When both the severe Boulez and the suave Duke Ellington cite you as a precursor, you have done something singular.

The music is easy to love but hard to explain. The shelf of books about Debussy is not large, and every scholar who addresses him faces the challenge of analyzing an artist to whom analysis was abhorrent. The latest addition to that shelf is Stephen Walsh’s “Debussy: A Painter in Sound” (Knopf), which places proper emphasis on Debussy’s myriad links to other art forms. The composer may have been the first in history to become a fully modern-minded artist, joining a community of writers and painters, borrowing ideas and lending them in turn. Admittedly, before Debussy there was Wagner, whose impact was sufficiently seismic that the term “Wagnerism” had to be coined to describe it. With Wagner, though, the influence tended to go in one direction: outward. Debussy was receptive. He saw, he read, he pondered, and he transformed the ineffable into sound.

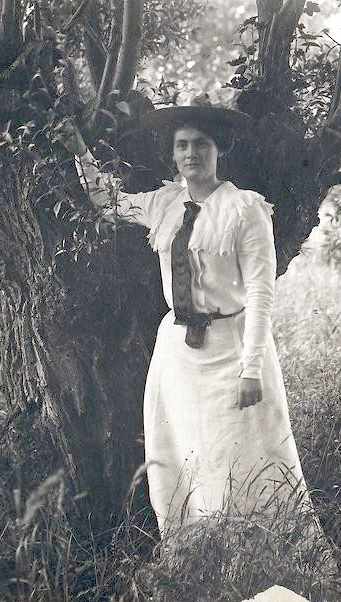

“He was a very, very strange man,” the soprano Mary Garden said. With his piercing eyes and jutting forehead, he could make a rough first impression—like “a proud Calabrian bandit,” according to the pianist Ricardo Viñes. François Lesure, the author of the definitive French-language biography of Debussy, portrays him as “withdrawn, unsociable, taciturn, skittish, susceptible, distant, shy.” He was said to be “catlike and solitary.” He “lived in a kind of haughty misanthropy, behind a rampart of irony.” He had a tendency toward mendacity in his professional and personal relationships. He was conscious enough of his limitations: “Those around me persist in not understanding that I have never been able to live in a real world of people and things.”

Debussy was born in the Paris suburbs in 1862, to an impoverished family. His father, Manuel, held a string of jobs, including china-shop owner, travelling salesman, and print worker. His mother, Victorine, was a seamstress. In the period of the Paris Commune, in 1871, Manuel served in the revolutionary forces, as a captain, and when the Commune was defeated he spent more than a year in prison. Fortuitously, when Manuel told Charles de Sivry, another inmate, about his son’s musical interests, Sivry mentioned that his mother, Antoinette Mauté, was a pianist. Mauté, a well-connected woman who was said to have studied with Chopin, began teaching the boy, and helped to arrange his admission to the Paris Conservatory, in 1872. Another notable thing about Mauté is that her daughter Mathilde had the misfortune of being married to Paul Verlaine. At the time, that ill-fated couple was living with Mauté, and Arthur Rimbaud, soon to become Verlaine’s lover, was an increasing source of tension. Although Debussy never spoke of meeting either Verlaine or Rimbaud, he must have been at least vaguely aware of the chaos in the household.

At the conservatory, Debussy was a restless student, exasperating his teachers and fascinating his schoolmates. When confronted with the fundamentals of harmony and form, he asked why any systems were needed. He had little trouble mastering academic exercises, and, after two attempts, he won the Prix de Rome, a traditional stepping stone to a successful compositional career. But in his early vocal pieces, and in his legendarily mesmerizing improvisations at the piano, he jettisoned rules that had been in place for hundreds of years. Familiar chords appeared in unfamiliar sequences. Melodies followed the contours of ancient or exotic scales. Forms dissolved into textures and moods. An academic evaluation accused him of indulging in Impressionism—a label that stuck.

Perhaps Debussy’s central insight was about the constricting effect of the standard major and minor scales. Why not use the old modes of medieval church music? Or the differently arrayed and tuned scales found in non-Western traditions? Or the whole-tone scale, which divided the octave into equal intervals? Debussy had a particular fondness for the natural harmonic series—the spectrum of overtones that arise from a vibrating string. If you pinch a taut string in the middle, its pitch goes up an octave. If you pinch it at successively smaller fractions, the basic intervals of conventional Western harmony emerge. So far, so good: but what about the notes further out in the series? These are more difficult to assimilate. In the chain of intervals derived from a C, you encounter a tone somewhere near B-flat and another in the vicinity of F-sharp. Debussy favoured a mode that has become known as the acoustic scale, which mimics the overtone series by raising the fourth degree (F-sharp) and lowering the seventh (B-flat). That those notes correspond to blue notes helps to explain Debussy’s appeal to jazz musicians.

Debussy had the prejudices typical of his time, and never thought too deeply about the cultures that he sampled. Nevertheless, he knew to look outside the classical sphere for nourishment. At the Paris Exposition of 1889, he heard a gamelan ensemble, which made Western harmonies sound to him like “empty phantoms of use to clever little children.” Those first measures of “Afternoon of a Faun” capture Debussy’s breadth of vision: first the call of the faun, which feels primal and uncomposed, and then that sumptuous chord on B-flat, which has no need to resolve, because it is complete in itself, a chord of overtones resting on its fundamental.

Debussy’s rejection of the musical status quo was fuelled by his jealous love of poetry and painting. The most revelatory experience I’ve had with the composer in recent years was not in the concert hall but in a museum: an exhibition entitled “Debussy, Music, and the Arts,” which was mounted at the Musée de l’Orangerie, in Paris, in 2012. To turn from the manuscript of “Faun” to a copy of Mallarmé’s poem, and then to see on the walls a Whistler seascape and Hokusai’s “Great Wave,” was to feel Debussy’s synesthetic kick. For him, music had fallen behind: it had nothing that rivalled free verse in poetry, the drift toward abstraction in painting, and the investigation of mystical spheres that was happening across the arts.

Poetry spurred Debussy’s earliest breakthroughs. His individual voice materializes in settings of Paul Bourget, Théodore de Banville, Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Mallarmé—poets who ranged from Parnassian classicism to Symbolist esotericism. Like a hunter chasing an elusive quarry, Debussy repeatedly tried to capture the eerie stillness of Verlaine’s “En Sourdine”: “Calm in the half-light / Made by the tall branches, / Let our love be imbued / With deep silence.” As Walsh observes, Debussy’s first attempts, from 1882, are thick with Wagnerian harmony. A version from a decade later is spare and piercing, all excess expunged. Debussy is ready to compose “Afternoon of a Faun,” which arose when Mallarmé asked him to contribute to a theatrical version of his poem. (No production resulted.) “Inert, all burns in this savage hour,” the poem reads, making oblique mention of “him who searches for the la”—the note A. This is the atmosphere of Debussy’s opening, with its charged stasis and its chords of resonance.

The visual arts proved an equally important fund of inspiration, although the Impressionist label has perpetuated the erroneous notion that Debussy tried to do in music what Monet, Renoir, and Degas did in painting. Those artists were in his field of vision, but the rush of brushwork that defines Impressionist painting—the erasure of the clean line in pursuit of a hazier reality—is alien to Debussy’s crystalline technique. Elusive but never vague, he is closer in spirit to the Symbolist movement, with its vivid evocations of unreal realms, and to the fable-bright world of Les Nabis. He also looked to the Pre-Raphaelites—“La Damoiselle Élue,” a pivotal early cantata, is based on Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s poem “The Blessed Damozel”—and to the semi-abstract seascapes of J. M. W. Turner, which forecast the tumult of “La Mer.”

The culmination of this first phase of Debussy’s revolution is “Pelléas et Mélisande,” an opera so unlike its predecessors that it effectively inaugurated a new genre of modernist music theatre. A tale of two half-brothers who fall in love with the same mysterious maiden, it is based on the eponymous play by the Belgian Symbolist Maurice Maeterlinck, who had a fin-de-siècle vogue before largely falling out of sight. Maeterlinck is worth revisiting—his elliptical dialogue looks ahead to the work of Samuel Beckett. Debussy, facing the gnomic text of “Pelléas,” made the radical decision to set it line by line, without recourse to a versifying librettist. This had been done before, notably in Russian opera, but Debussy achieved an unprecedented merger of music with an advanced literary aesthetic. In the wake of “Pelléas” came Strauss’s “Salome” and “Elektra,” Berg’s “Wozzeck” and “Lulu,” and Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s “Die Soldaten.”

“Pelléas” engenders its own world on the first page of the score. In an essay in the new scholarly anthology “Debussy’s Resonance” (University of Rochester Press), Katherine Bergeron indicates how this happens. In the first four bars, bassoons, cellos, and double basses make a stark, columnar sound that conjures the forest in which the drama begins. It is, Bergeron writes, an evocation of “dim antiquity, carving out a fragment of plainsong in stolid half notes.” She continues, “The figure suggests an immense murmur, or an ancient cosmic sigh, whose sheer weight draws it to the bottom of the orchestra. Then it vanishes. A different music takes its place, sounding high in the winds, its bass voice a tritone away. With its more articulate rhythm and brighter timbre, the melody sounds a sort of anxious trill: indecisive, edgy, almost dissonant.” This second motif is associated with Golaud, who ends up killing his half-brother, Pelléas. Golaud, Bergeron observes, seems strikingly disconnected from the forest around him. We hear not only two distinct textures but the gap between them. This defining gesture is painterly at heart: a single stroke of the brush turns the remainder of the canvas into resonant space.

The première of “Pelléas,” in 1902, established Debussy as the dominant French composer of his time. He became a trend, a “school”: critics spoke of “Debussystes” and “Debussysme.” For a man accustomed to thinking of himself as a loner, the fame was disconcerting. His life was further complicated by personal chaos, largely of his own making. His first marriage, to the fashion model Lilly Texier, fell apart when he began an affair with the singer Emma Bardac. In 1904, Texier attempted suicide; the affair became public, and Debussy lost many friends. He subsequently married Bardac. That relationship, too, was troubled, although it lasted until his death. “An artist is, all in all, a detestable, inward-facing man,” Debussy wrote to Texier in 1904, as if brutal candor somehow excused his behavior.

In this period, Debussy took up a second career, as a music critic, delivering a stream of prickly, contrarian opinions that seemed almost designed to increase his isolation. Beethoven wrote badly for the piano, he proclaimed: “With a few exceptions, his works should have been allowed to rest.” Wagner was a literary genius but no musician. Gluck was pompous and artificial. There was a method to this crankiness: Debussy was attacking the tendency to worship the past at the expense of the present. In a later interview, he said that he actually admired Beethoven and Wagner, but refused to “admire them uncritically, just because people have told me that they are masters.”

Debussy struggled to come up with a successor to “Pelléas.” His list of contemplated operas included a setting of Pierre Louÿs’s “Aphrodite”; an adaptation of Shakespeare’s “As You Like It”; and works on topics as various as Siddhartha, Orpheus, the Oresteia, Don Juan, Romeo and Juliet, and Tristan and Yseult (“a subject which has not as yet been treated,” Debussy said, impishly). Not all these ideas were serious; Debussy had a bad habit of seeking advances for projects that he had little intention of completing. He did, however, expend considerable energy on a pair of operas inspired by Edgar Allan Poe: a comedy, based on “The Devil in the Belfry,” and a tragedy, based on “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Enough sketches for the latter exist that the scholar Robert Orledge has been able to make a stylish and often convincing reconstruction, which the Pan Classics label recorded in 2016, alongside a less persuasive version of the “Belfry” material.

If Debussy’s operatic path remained largely blocked, he found new fluency in the production of instrumental scores: the three sets of “Images” for piano and for orchestra, the two books of Preludes for solo piano, “La Mer,” and the dance score “Jeux.” In this pervasively dazzling body of music, Symbolist gloom gives way to glowing new colours and a fresh rhythmic punch. Popular influences come to the fore: vaudeville tunes, circus marches, cabaret, Iberian dances, ragtime.

While exploring the D.G. Debussy box, the richer of the two collections, I found myself fixated on Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli’s casually immaculate rendering of “Reflets dans l’Eau,” from the first book of “Images.” Michelangeli’s recording of “Images,” made in 1971, is rightly regarded as one of the greatest piano records ever made. “Reflets” begins with eight bars confined to the key of D-flat major, or, more precisely, to the scale associated with that key. Chords drawn from those seven notes lounge indolently across the keyboard. In the ninth bar, though, the work goes gorgeously haywire. Extraneous notes invade the inner voices, even as a D-flattish upper line is maintained. Pinprick dissonances disrupt the sense of a tonal center, and the music collapses into harmonic limbo, in the form of a rolled chord of fourths. This is Debussyan atonality, which predates Schoenberg’s and is very different in spirit: not a lunge into the unknown but a walk on the wild side. We stroll back home with a descending string of chords that defy brief description: sevenths of various kinds, diminished sevenths, dominant sevenths, and what, in jazz, is called the minor major seventh. Michelangeli, who admired the jazz pianist Bill Evans and was admired by Evans in turn, plays this whole stretch of music as if he were hunched over a piano in a smoke-filled club, at one in the morning, sometime during the Eisenhower Administration. Two bars later, we are back in D-flat—an even more restricted version of it, on the ancient pentatonic scale. Some kind of bending of the musical space-time continuum has occurred, and we are only sixteen bars in.

Debussy is often stereotyped as an artist of motionless atmospheres, but he was a radical in rhythm as well as in harmony. I’ve also become mildly obsessed by a few bars in the propulsive final movement of “La Mer,” entitled “Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea,” which is structured around successive iterations of a simple theme of narrow falling intervals: A to G-sharp, A-sharp to G-sharp. As in “Afternoon of a Faun,” an idea remains largely fixed while the context around it undergoes kaleidoscopic changes. First the theme sounds in the winds, over rapidly pulsing lower strings; then it hovers in an ambience of luminous calm; then it takes on an impassioned, quasi-Romantic character in the violins.

The fourth iteration never fails to make me want to leap from my chair. The downward-sighing theme is back in the winds, but it floats above a multilayered texture in which rhythms and accents are landing every which way: scurrying triplets in the strings, horns sounding on the fourth beat of the bar, piercing grace notes in the piccolo, and a curious oompah section comprised of timpani, cymbals, and bass drum. Most of the instruments are dancing to the side of the beat. The net result of all this layering is an irresistible sense of buoyancy. Particularly striking is a galloping pattern in the strings—four rapid hoofbeats endlessly recurring. Debussy liked the work of the British painter and illustrator Walter Crane, and I wonder whether “La Mer” might have something to do with Crane’s 1892 painting “Neptune’s Horses,” in which phantom beasts materialize from a cresting wave.

The D.G. box includes two performances of “La Mer”: one with the Santa Cecilia Orchestra, under Leonard Bernstein, and one with the Berlin Philharmonic, under Herbert von Karajan. Both make an impressive noise at the climaxes, although they fall prey to an aggrandizing tendency noted by the scholar Simon Trezise, in a book-length study of “La Mer.” Since Toscanini, Trezise argues, conductors have made “La Mer” an “orchestral showpiece of the first order,” rather than a complexly layered conception in which foreground and background merge. Trezise rightly draws attention to pioneering recordings by the Italian conductor Piero Coppola, in which the strings are restrained in favor of pungent winds. That leanness and a vibrancy of colour reëmerge in a 2012 rendition of “La Mer” by Jos van Immerseel and the ensemble Anima Eterna Brugge, which uses instruments from Debussy’s era.

Still, I cherish most the various recordings made by Boulez, who dedicated himself to banishing all sentimental mists from Debussy’s music, thereby exposing its modernity. Regrettably, Boulez’s 1995 reading with the Cleveland Orchestra is missing from the D.G. box, but the set does include his staggeringly precise account of “Jeux.” In the finale of “La Mer,” Boulez’s meticulous attention to rhythmic subtleties redoubles the music’s kinetic energy. When he led the New York Philharmonic in “La Mer” in 1992—his final appearance with that ensemble—the waves broke on the ears with cold, lashing force.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mGqLaD_zaU&feature=youtu.be&t=1386

In 1913, Debussy arrived at the inevitable moment when he no longer occupied the vanguard. That year, the Ballets Russes unleashed Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring.” Debussy marvelled at Stravinsky’s invention, but felt uneasy about his younger colleague’s ruthless brilliance. “Primitive music with all modern conveniences” was his wry comment on the “Rite.” The advent of full-on atonality in the music of Schoenberg and his pupils left Debussy cold. He loved the strange but not the harsh.

As Europe devolved into barbarism in the early years of the First World War, Debussy adopted a decorous, formally controlled style that looked back to the aristocratic poise of the French Baroque. With this unexpected swerve, he was following the advice he gave to his stepson, to “distrust the path that your ideas make you take.” As Walsh points out, Debussy’s self-distrust considerably slowed his productivity, as he tested “every chord and chord sequence, every rhythm, every colour for their precise effect.”

In the summer of 1915, Debussy embarked on a cycle of six sonatas for different groups of instruments—a telling gesture, since up to this point he had largely ignored the received forms of classical tradition. In a burst of creativity, he completed two of them in a matter of weeks: the Cello Sonata and the Sonata for Flute, Viola, and Harp. A Violin Sonata followed. He considered these works a “secret homage” to French soldiers fallen in battle. In a patriotic mood, he signed them “Claude Debussy, French musician.” They forecast the West’s turn toward neoclassicism in the postwar period, not least in Stravinsky’s ever-evolving, fashion-setting œuvre. Yet Debussy avoided intellectual irony or self-consciousness. He saw himself as restoring the beauty that had been destroyed in the war.

The Harmonia Mundi label has added to the welcome flood of Debussy on disk with its own Centenary Edition, and one of its finest offerings is a survey of those three sonatas. Isabelle Faust and Alexander Melnikov play the Violin Sonata; Jean-Guihen Queyras and Javier Perianes undertake the Cello Sonata; and the flutist Magali Mosnier, the violist Antoine Tamestit, and the harpist Xavier de Maistre give a pristine performance of the sonata dedicated to their instruments. That piece is sometimes so sparing in its application of notes to the page that it hardly seems to exist. The score contains such indications as “dying away” and “as delicately as possible.” This is music suffused with pale light; each terse, tender phrase seems aware of its own impermanence.

Debussy had found a new path—beyond Symbolism, beyond modernism. One can only wonder what might have followed, for his life came to a grim end. In 1915, he was given a diagnosis of rectal cancer and underwent an operation that had limited success. His final years were horrible. He suffered from incontinence and stopped leaving the house. He died as German forces were shelling Paris. Afterward, his twelve-year-old daughter, called Chouchou, wrote a heartbreaking letter to her half-brother: “I saw him again one last time in that horrible box—He looked happy, oh so happy.” Chouchou died the following year, of diphtheria—a fate of which Debussy, blessedly, had no inkling. She may have been the only person he ever loved without reserve.

Republished with permission from The New Yorker.