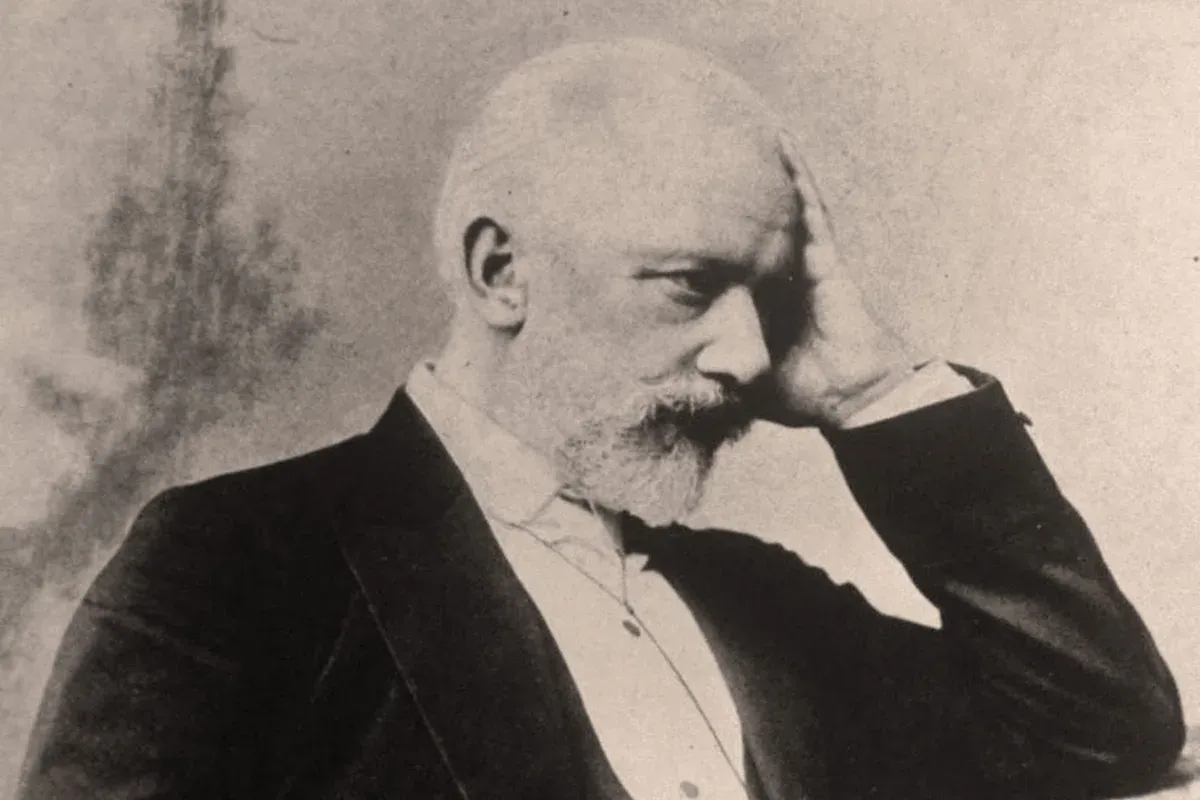

The Tragic Life and Timeless Music of Tchaikovsky

Behind Tchaikovsky’s soaring melodies lies a life marked by secrecy, emotional turmoil and relentless self-doubt. Yet from this turbulence emerged ballets, symphonies and concertos of extraordinary beauty that continue to move audiences across the world.

Few composers embody the idea of the tortured Romantic artist as completely as Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. His music surges with yearning, despair, tenderness and triumph. His melodies are among the most recognisable in Western classical music. Yet behind the sweeping waltzes and heart-stopping climaxes lay a life marked by insecurity, emotional turmoil and an unrelenting search for acceptance.

To reduce Tchaikovsky to tragedy alone would be simplistic. He was disciplined, intellectually curious and acutely aware of his craft. But there is no denying that the tensions of his private life and the pressures of public expectation shaped his artistic voice in profound ways.

A Childhood of Sensitivity and Loss

Born in 1840 in Votkinsk, then part of the Russian Empire, Tchaikovsky grew up in a cultivated household. Music was present from an early age, and his sensitivity to sound was evident. Yet his childhood was shadowed by emotional upheaval.

At the age of ten, he was sent away to boarding school in St Petersburg. The separation from his mother, to whom he was deeply attached, left a lasting wound. When she died of cholera in 1854, the loss devastated him. Letters from this period reveal an almost unbearable grief. The emotional intensity that would later animate his music was already taking shape.

Despite early musical promise, Tchaikovsky did not initially pursue composition as a profession. He trained in law and worked briefly as a civil servant. Only in his early twenties did he enrol at the newly founded St Petersburg Conservatory, committing himself fully to music.

Between Russia and the West

Tchaikovsky’s artistic position was complicated. In 19th-century Russia, debates raged about national identity in music. The so-called Mighty Handful championed a distinctly Russian style rooted in folk song and orthodoxy, often rejecting Western academic traditions.

Tchaikovsky, by contrast, embraced formal training. He admired Mozart and Beethoven and absorbed German symphonic models. This dual allegiance left him vulnerable to criticism from both sides. Some Russian nationalists saw him as insufficiently authentic. Some Western critics heard in his music an exoticism tinged with excess.

Yet it is precisely this synthesis that gives his music its distinctive voice. The ballets Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beautyand The Nutcracker combine French elegance, Italian lyricism and Russian colour into scores of extraordinary theatrical vitality. His symphonies, particularly the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth, fuse Western structural rigour with an unabashed emotional directness.

A Marriage of Desperation

No discussion of Tchaikovsky’s life can ignore the anguish surrounding his sexuality. Living in a society that criminalised homosexuality, he was forced into secrecy. The psychological strain of concealment weighed heavily.

In 1877, in what many biographers interpret as an attempt to conform to social expectations and silence rumours, Tchaikovsky married Antonina Milyukova. The marriage was a catastrophe. He had no romantic feelings for her and was repulsed by physical intimacy. Within weeks, he suffered a nervous collapse.

The separation that followed was both scandalous and necessary. He fled Moscow and sought refuge abroad. The episode left him shaken but also marked a turning point. From this crisis emerged some of his most powerful music, including the Fourth Symphony, whose ominous opening fanfare he described as representing Fate.

It would be tempting to draw a direct line from personal misery to musical greatness. The reality is more complex. Tchaikovsky worked tirelessly at his craft. He revised scores meticulously and was often dissatisfied with his own efforts. Emotional pain may have fuelled urgency, but artistry required discipline.

The Patron Who Changed Everything

In the wake of his marital disaster, Tchaikovsky’s life was transformed by an extraordinary relationship with a wealthy widow, Nadezhda von Meck. She offered him financial support on the condition that they never meet. For thirteen years, they corresponded intensely while remaining physically apart.

Von Meck’s patronage allowed Tchaikovsky to resign from his teaching post and devote himself entirely to composition. Their letters reveal intellectual companionship and mutual admiration. He dedicated works to her, including the Fourth Symphony.

The arrangement ended abruptly in 1890 when von Meck, citing financial difficulties, withdrew her support. Tchaikovsky was deeply hurt, though he maintained outward composure. By then, however, his international reputation was secure.

The Pathétique and the Shadow of Death

Tchaikovsky’s final years were marked by both acclaim and fragility. He travelled widely, conducting his own works in Europe and America. Audiences responded passionately to his music’s emotional immediacy.

In 1893, he completed his Sixth Symphony, later known as the Pathétique. Unlike traditional symphonies that end in triumph, this work concludes in a slow movement of haunting resignation. Its closing pages fade into darkness.

Nine days after conducting its premiere in St Petersburg, Tchaikovsky died, officially of cholera. The circumstances have long been debated. Some scholars have suggested suicide under pressure related to his sexuality, though definitive evidence remains elusive.

The Pathétique inevitably invites biographical interpretation. Is it a farewell? A confession? Or simply an exploration of despair shaped by musical logic rather than autobiography? The ambiguity is part of its enduring power.

Music That Refuses to Fade

For all the drama of his life, it is the music that continues to speak. The Violin Concerto, once dismissed as unplayable, is now a cornerstone of the repertoire. The First Piano Concerto, with its thunderous opening chords, remains electrifying. The ballets fill theatres each season, their melodies woven into popular culture.

What makes Tchaikovsky timeless is not merely emotional intensity but melodic genius. He had an uncanny ability to craft themes that lodge in the memory. These melodies are often simple, even songlike, yet they unfold within sophisticated harmonic frameworks.

He also understood orchestral colour instinctively. The shimmer of strings, the plaintive cry of woodwind, the blaze of brass at moments of climax, all are handled with theatrical flair. His experience in opera informed his symphonic writing; he thought in terms of drama and gesture.

Critics have sometimes accused Tchaikovsky of sentimentality. The charge misunderstands the precision of his construction. Beneath the sweeping melodies lies careful architecture. Climaxes are prepared meticulously. Contrasts are calibrated. The emotional impact is earned.

The Human Voice Behind the Sound

Perhaps the enduring fascination with Tchaikovsky stems from the sense that his music exposes vulnerability. Where some composers project stoic grandeur, he seems to invite the listener into an intimate emotional landscape.

This openness resonates across cultures and generations. Listeners who know nothing of 19th-century Russia can still feel the ache of the slow movement of the Fifth Symphony or the bittersweet nostalgia of The Nutcracker’s waltzes.

Yet it is important not to romanticise suffering. Tchaikovsky’s life was not a melodrama scripted for artistic effect. It was a human life shaped by social constraints, personal doubts and moments of joy as well as despair. He valued friendship, loved nature and took pride in his achievements.

Tragedy Transformed

The phrase ‘tragic life’ captures only part of the story. Tchaikovsky experienced anguish, certainly. But he also achieved professional success, international recognition and artistic fulfilment. His ability to transform private turmoil into universally resonant art is what secures his place in history.

In the concert hall, the biographical details recede. What remains is the sound: the surge of strings, the hush before a final chord, the release of applause. The music does not demand that we know the composer’s struggles, yet it seems to carry their imprint.

More than a century after his death, Tchaikovsky’s works continue to draw audiences into their emotional orbit. They remind us that vulnerability and strength can coexist, that discipline can shape passion into form, and that beauty can emerge from even the most conflicted of lives.