The Rebels of Classical Music: How Iconic Composers Broke the Rules and Redefined the Art

Throughout history, rebellious composers like Beethoven, Berlioz, Stravinsky, and Shostakovich have challenged conventions, reshaping classical music with daring innovations. Their groundbreaking works expanded symphonic form, orchestration, and narrative, leaving a lasting impact on the art form.

In the world of classical music, it’s often assumed that the path to greatness lies in adhering to tradition, respecting the rules, and remaining faithful to established forms. Yet, when we examine the careers of the most influential composers, we see a different story emerge: they weren’t followers of tradition, but revolutionaries who upended the status quo and, in doing so, shaped the course of music history. These composers didn’t just play by the rules—they bent them, broke them, and created new ones. From Beethoven’s reimagining of symphonic structure to Stravinsky’s riot-inducing ballet scores, the impact of their rebellious spirits still resonates today.

Let’s dive into the stories of these musical mavericks who dared to break the mold and transformed classical music into the living, breathing art form we know today.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Rewriting the Symphony

Before Ludwig van Beethoven, the symphony was a tightly structured form, often written in four movements, adhering to predictable patterns in tempo and key. Composers like Haydn and Mozart created masterpieces within this structure, following the “rules” laid out by music theorists of the time. But Beethoven wasn’t satisfied with working within these constraints. He sought to express profound emotions and philosophical ideas through his music, and the established forms simply couldn’t contain his vision.

One of Beethoven’s most radical innovations came in his Symphony No. 3, the “Eroica”. Originally dedicated to Napoleon Bonaparte, the work shattered expectations with its scale, complexity, and intensity. It was longer than any symphony before it, with a first movement so emotionally charged that it left audiences and critics bewildered. Beethoven also expanded the development section—where musical themes are traditionally explored and transformed—turning it into a dramatic battlefield of ideas.

The symphony’s second movement, a funeral march, was equally groundbreaking. In previous symphonies, slow movements were often lyrical or serene, but Beethoven infused this one with a tragic, almost political, weight. The entire work challenged the conventions of what a symphony could be, and in doing so, set the stage for the Romantic era, where emotional expression would take precedence over formality.

Beethoven’s rebellious streak wasn’t limited to structure. His Ninth Symphony, with its choral finale featuring “Ode to Joy”, broke the ultimate taboo—introducing voices into a symphony. The notion of blending vocal and orchestral forces in this context was unprecedented, and yet it has since become one of the most iconic pieces in classical music, its theme now recognized worldwide as a symbol of unity and freedom.

By daring to expand the symphony beyond its classical boundaries, Beethoven redefined the very essence of the genre, leaving a legacy that would inspire future composers to push against the limitations of form and convention.

Hector Berlioz: The Orchestration Pioneer

If Beethoven redefined the symphony, then Hector Berlioz redefined the orchestra itself. Born in 1803, Berlioz came of age during a time when the orchestra was still relatively small and conservative in its instrumentation. Yet Berlioz had grander visions. He believed the orchestra was capable of expressing a much wider range of colors, emotions, and effects than anyone before him had imagined. To achieve this, he expanded the size and scope of the orchestra, pushing orchestral music into new, uncharted territories.

Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique is perhaps the best example of his innovative spirit. Written in 1830, it tells the story of an artist driven to madness by unrequited love, with each movement depicting a different stage of his emotional descent. In addition to its radical narrative structure—effectively turning the symphony into a programmatic work, or a piece that tells a story through music—Berlioz’s orchestration is breathtaking in its inventiveness. He used the orchestra in ways that had never been heard before, employing a vast array of instruments to create vivid soundscapes.

For instance, in the famous “March to the Scaffold” movement, Berlioz uses a heavy brass section to create a sense of impending doom, while in the “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath”, he conjures a chaotic, nightmarish atmosphere through the use of eerie, dissonant strings and strange effects like col legno (tapping the strings with the wood of the bow). Berlioz’s writing for the orchestra was so advanced that many orchestras of his time struggled to perform his works.

Beyond his own compositions, Berlioz was a key figure in the development of modern orchestration. His treatise on orchestration, published in 1844, became a foundational text for composers learning how to write for the orchestra, influencing generations of musicians to come, including Wagner, Mahler, and Richard Strauss. His rebellious approach to instrumentation and his refusal to be bound by tradition allowed the orchestra to evolve into the powerful, expressive force that it remains today.

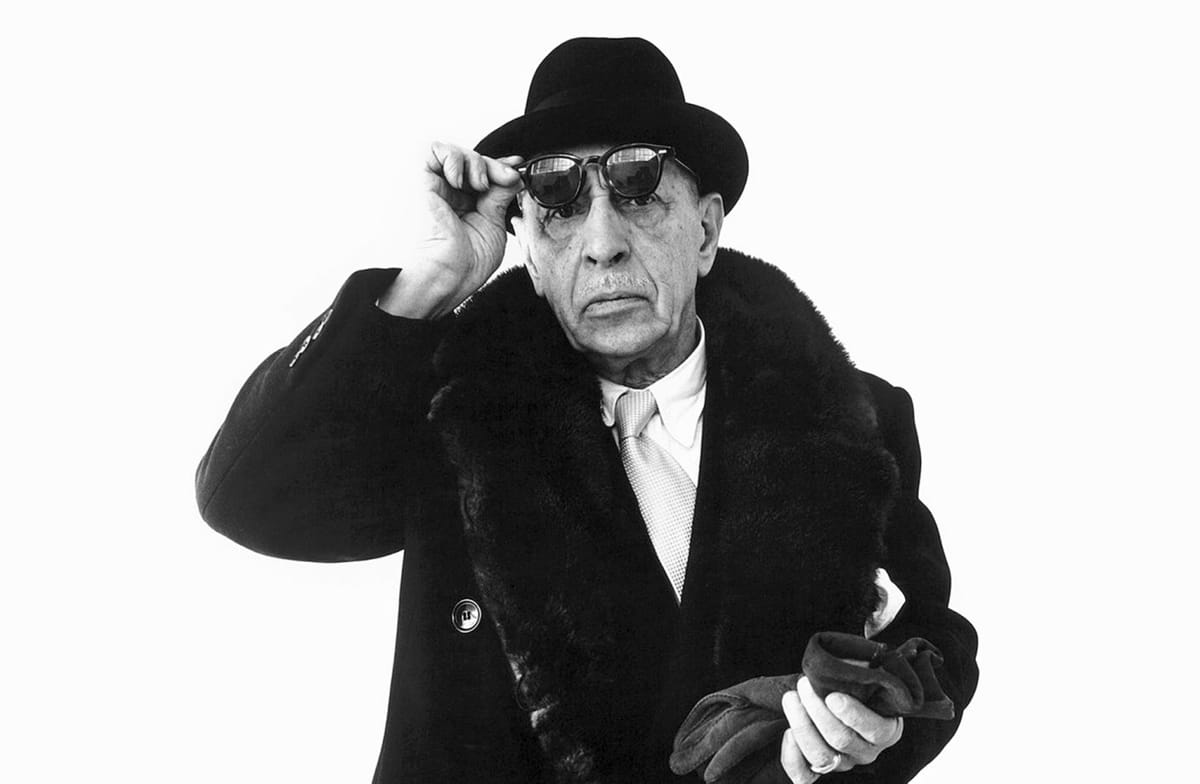

Igor Stravinsky: The Ballet Revolutionary

Few composers can claim to have caused an actual riot with their music, but Igor Stravinsky did just that. On May 29, 1913, the premiere of Stravinsky’s ballet The Rite of Spring at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris erupted into chaos. The audience, shocked by the music’s savage rhythms, dissonant harmonies, and jarring orchestration, booed, shouted, and even fought in the aisles. The scandalous choreography, which featured dancers stomping and twisting in primitive movements, only added fuel to the fire.

But why did The Rite of Spring provoke such a violent reaction? At its core, the piece was a radical departure from everything that had come before. Stravinsky rejected the lush, lyrical sounds of late Romanticism in favor of raw, primal energy. The music is built around complex, irregular rhythms—far removed from the elegant, flowing meters of traditional ballet scores. The harmony, too, is jarring, with dissonant chords piled on top of one another, creating a sense of tension and instability.

The work’s subject matter—a pagan ritual in which a young girl dances herself to death—also broke with the genteel traditions of ballet, where stories were often drawn from fairy tales or classical mythology. Stravinsky’s vision was darker, more visceral, and altogether more modern. Although the premiere was a scandal, The Rite of Spring quickly gained recognition as a masterpiece, and its influence on the course of 20th-century music cannot be overstated. Composers like Bartók, Prokofiev, and even jazz musicians would draw on its rhythmic complexity and daring harmonic language in their own works.

Stravinsky’s rebellion wasn’t just about breaking the rules—it was about creating a new musical language that reflected the chaos and complexity of the modern world. In doing so, he paved the way for countless other composers to experiment with form, rhythm, and harmony in ways that continue to shape contemporary music.

Dmitri Shostakovich: A Covert Challenger of Authority

While Beethoven, Berlioz, and Stravinsky rebelled against musical tradition, Dmitri Shostakovich found himself rebelling against a far more dangerous authority: the Soviet government. In a regime where artists were expected to conform to strict ideological guidelines—producing art that glorified the state and conformed to socialist realism—Shostakovich walked a perilous tightrope. His music had to appease government censors while subtly expressing his personal struggles and, at times, his deep-seated criticisms of the regime.

Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 is a brilliant example of his ability to work within the system while simultaneously undermining it. Written in 1937 after his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk was denounced by the Soviet authorities, the Fifth Symphony was officially presented as “a Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism.” On the surface, it seemed to conform to the ideals of socialist realism, with its triumphant finale symbolizing the victory of the people. But beneath the surface, the music tells a different story.

Many listeners have interpreted the symphony’s finale as a forced, hollow triumph, with its relentless, almost mechanical repetition of a single theme suggesting not genuine joy, but coercion. Shostakovich himself is rumored to have said, “The rejoicing is forced, created under threat. It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, ‘Your business is rejoicing.’

Shostakovich’s ability to embed hidden meanings and veiled criticisms in his music made him a rebellious figure in a uniquely Soviet sense. He used music not only to survive within an oppressive regime but also to resist it in subtle, coded ways. In doing so, he became an emblem of artistic defiance in the face of tyranny, proving that rebellion can take many forms—even under the most dangerous circumstances.

The Spirit of Rebellion

What unites these composers across centuries and styles is their refusal to accept the status quo. Whether it was Beethoven’s radical expansion of symphonic form, Berlioz’s visionary use of the orchestra, Stravinsky’s bold embrace of modernism, or Shostakovich’s subversive critiques of totalitarianism, each of these composers took risks that forever changed the landscape of classical music. Their innovations were not always immediately accepted—sometimes, as in the case of Stravinsky, they provoked outrage—but their willingness to break the rules has inspired generations of musicians to challenge conventions and push boundaries.