The Priceless Heritage

Since its beginning, the NCPA’s performing arts archive has preserved a staggering 6,200 hours of music, 1,250 hours of video recording, 300 hours of folk music and 65 hours of film recordings. By Anil Dharker

‘Archive’ is a wonderfully evocative word, suggesting a civilisation, which values its past enough to preserve it. Given the antiquity of human existence, it is a fairly recent formulation, having been coined in 1638. That is when countries such as England realised that the past, if not carefully looked after, would really become a thing of the past and future generations would be bereft of a tangible sense of history.

Human history would then exist only in textual form – but even this would be extremely limited because what text would do justice to the performing arts? Who could describe a special performance of Swan Lake by the Bolshoi Ballet or a wonderful recital by Balasaraswati? Those of us who revere the magic of the human voice have heard of Enrico Caruso, but can we actually hear him unless his recitals are preserved somewhere? Will our children have the slightest idea of what Bhimsen Joshi sounded like and the mesmerising quality of his performances (the theatricality of his hands doing their own independent acts, seemingly plucking musical notes from the air)? Unless, of course, someone, somewhere preserves them.

EVIDENT TRUTHS

These things should be self-evident, but in our country they are not. As a nation we talk endlessly of our ancient culture, but do nothing to preserve it. You just have to go to any of our historical sights to know that this damning generalisation is sadly true. It may be politically incorrect to say so, but much of our past would have vanished were it not for the British Empire (it is another matter they purloined many of our antiquities to preserve them in the British Museum and similar institutions). To give a more recent example, even Satyajit Ray’s films would have been lost forever had Ismail Merchant not stepped in and raised funds for their restoration.

Thoughts like these must have been at the forefront of Dr. Jamshed Bhabha’s mind when he set up the NCPA, initially at the Bhulabhai Desai Auditorium in Warden Road. In fact, his proposal to the Tata group for setting up the NCPA emphasised the need for an archive that would preserve our performing arts, which is why archival activity actually began on August 12, 1970, at the Bhulabhai Desai facility with a recording of Ahmad Jaan Thirakawa. And when the NCPA moved to its current location at Nariman Point, this was one of its central priorities.

THE MUSICAL PANTHEON

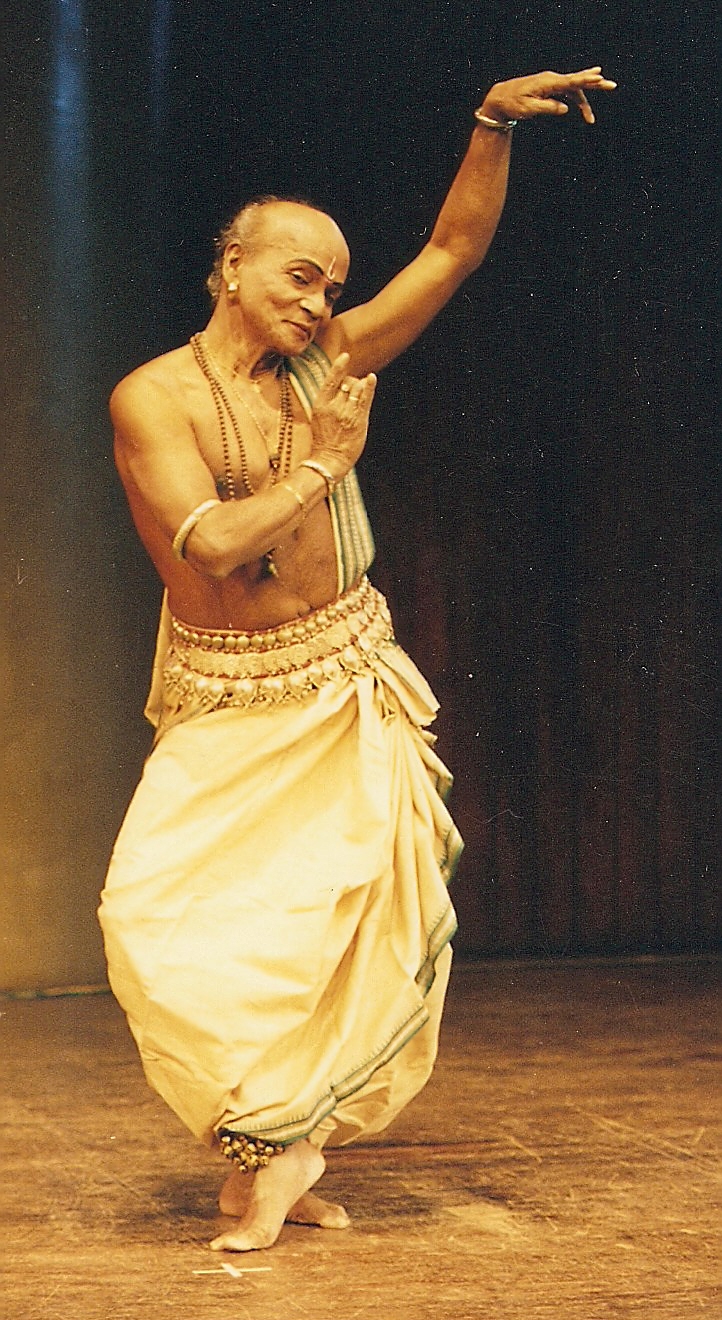

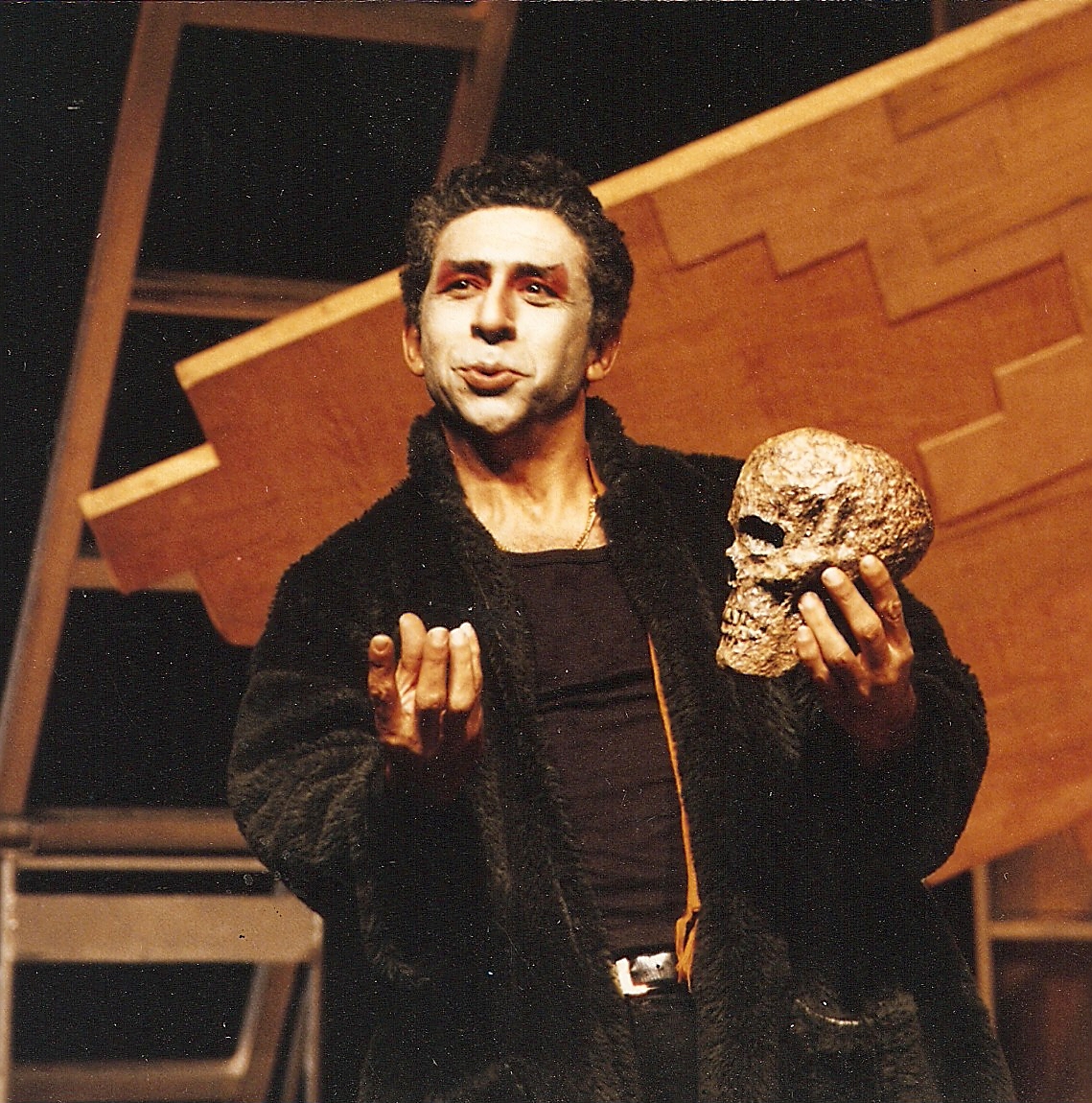

Dr. Bhabha found an able ally in Dr. Narayan Menon, the NCPA’s first executive director. Dr. Menon was a musicologist and had recently retired as director general of All India Radio. So, his background was full of Indian classical music in its many forms. When the NCPA’s 114-seater Little Theatre was commissioned, it was acoustically designed as a sound recording studio for Indian music, equipped with the latest professional equipment of that time, manufactured by the best international companies. While live events were indeed held, recording of eminent artistes began simultaneously. The roll call of musicians recorded by the NCPA consists of the pantheon of our musical greats such as M. S. Subbulakshmi, Gangubai Hangal, Vilayat Khan, Ali Akbar Khan, Begum Akhtar, Lalgudi Jayaraman and a whole host of others totalling more than 90 in all. Western musicians such as Yehudi Menuhin were also recorded while dancers of the calibre of Kelucharan Mohapatra, Mrinalini Sarabhai, Sonal Mansingh and others were captured on video.

The roll call of musicians recorded by the NCPA consists of the pantheon of our musical greats such as M. S. Subbulakshmi, Gangubai Hangal, Vilayat Khan, Ali Akbar Khan, Begum Akhtar and Lalgudi Jayaraman

Nayan Kale, the technical head of the NCPA, remembers the early days when he had just joined the organisation as a young man. “Dr. Narayan Menon not only chose the artiste to be recorded, he used his pre-eminent position in the field of music to get the very best performers to come to Bombay and record,” he says. “Did you know Bismillah Khan and his troupe came all the way from Lucknow and they only charged their train fare? No fees at all.” This, one supposes, was not just the case of Dr. Menon’s clout; it was also a measure of the musicians’ realisation that the NCPA’s archives would preserve their voice for the future. Kale remembers Dr. Menon sitting in on recordings at the Little Theatre and even dictating to musicians what they should play or sing. He says, “Dr. Menon would tell them, ‘Please don’t play what you play outside every day. I want a special performance, one which deserves to be preserved for posterity.’ They always obliged.”

ONLY THE BEST

The NCPA also acquired a mobile recording van, especially built on a chassis supplied by Telco and equipped with the then state-of-the-art air-conditioning and professional tape recorders. Dr. Sunil Kothari, India’s foremost authority on dance, arranged folk music performances in rural areas of Maharashtra, Gujarat and Rajasthan with the idea of recording and preserving them. Dance performances especially arranged at the Little Theatre were also recorded on the very best professional equipment of the time such as Arriflex cameras and Nagra tape recorders.

Till the end of last year, the NCPA had archived a staggering library of our heritage: 6,200 hours of music, 1,250 hours of video recording, 300 hours of folk music and 65 hours of film recordings. It is all there, locked up above the Little Theatre on the first floor in preservation vaults. There are two of them, one for the storage of audio, video and films and the second for storing photographic material. The vaults have double walls for thermal insulation, lined with aluminium foil and painted with special paints to make the brick walls impervious to weather conditions. All this is necessary to ensure that the vaults maintain the internationally recommended temperature between 21 and 23 degrees and relative humidity between 45 and 50 percent. (In Mumbai, during the monsoon, temperatures can reach 38 degrees while relative humidity can reach a sweltering 95 per cent).

Recordings were done on archival magnetic tape – remember this was the analogue age when spool tape recorders were used. When the digital era dawned, the NCPA began the painful process of transferring audio and video recordings into the digital form of hard disk, DVD and CD, obviously all of professional quality. The process is painful because the transfer has to be in real time, i.e., if the taped material is two hours long, it will take two hours to transfer. Kale shares an interesting story here – the NCPA’s Nagra tape recorders had stopped working and could not be repaired anywhere in India. That is when the Nagra Company itself came to the rescue, “The NCPA has been one of our best customers,” Nagra said. “We will do this for you.” “This” entailed manufacturing two tape recorders especially for the NCPA, years after they were discontinued, the very last Nagra ever produced.

THE DIGITAL ART

Digitalisation has many advantages: storage takes far less space and is not so demanding of weather fluctuations; there is very little degradation of quality; and, importantly, it makes retrieval easy, which means if a member wants to listen to a particular recording, the process will be instant. This will be a boon not just for the NCPA’s archival collection, but also its Stuart-Liff collection, which contains a massive 11,000 priceless LPs and 6,000 books.

George Stuart and Vivian Liff were two Englishmen with a shared interest in Western classical music, especially recordings of the human voice. They were collectors of 78 rpm records and later LPs when they came to the market. When their collection became too large for their London flat, they did not stop collecting. Instead, they sold the flat and moved to a large house in Kent where their collection could grow. By the mid ’70s, their collection had become one of the most comprehensive private collections of historical vocal recordings in the UK, much in demand everywhere, including BBC Radio. In 1981, unable to cope with the demands made of them, they accepted an offer from J. Paul Getty to sell their entire 78 rpm collection to him for a sum that reached several million pounds. But the LPs and books were still with them.

“Through my friendship with Khushroo Suntook, I had heard about the NCPA, which seemed to be the perfect repository for the collection”

NCPA Chairman, Mr. Khushroo N. Suntook, whose knowledge of Western classical music is encyclopaedic, is also an avid collector of 78s, LPs and CDs. During one of his trips to England years ago, he was introduced to Stuart and Liff, thus starting a friendship that has lasted for over 30 years. When Stuart died in 2007, Liff told Suntook that he would give away his collection to the NCPA. Not unexpectedly, there was a hue and cry in England: why should this priceless collection not stay in the country? Why should it be given away? But Liff had made up his mind. As he said in a letter at the time, “Through my friendship with Khushroo Suntook, I had heard about the NCPA, which seemed to be the perfect repository for them. With India emerging as one of the most important and influential countries in the world, a wealth of musical talent awaits discovery and nurture. It must be hoped that this initial donation from the Stuart-Liff Collection will prove of real use in encouraging and sustaining this aim.”

THE ENTIRE UMBRELLA

Between its archival and Stuart-Liff collections in digitised form, the NCPA possesses an unparalleled source of material on music and the performing arts, which would be of use and delight to the layman as well as the scholar. But that is not all: the NCPA also has a library containing 25,000 books on these subjects. Initially, the library contained only books donated to it, but a Ford Foundation grant enabled it to start its own collection when the doyen of Marathi theatre, P. L. Deshpande was its executive director. Under the eminent musicologist Dr. Ranade, the library embarked on an ambitious acquisition programme. Mrs. Madiman, who was the librarian at the time, talks about how the library’s collection was enlarged by getting books on subjects such as anthropology (dance forms and festivals of different tribes of India), religion and music (which are so inextricably intertwined), on the overall cultural history of India, biographies of performing artistes, books on the importance of dance and music in mythology and so on.

Members of the general public who go to the NCPA’s many programmes, and even its dedicated members, may not be aware of the treasures enclosed within its walls. The NCPA’s archives and library, and its Stuart-Liff collection add up to a vast storehouse of our cultural history. It is a magnificent gift for today’s generation. And an irreplaceable one for the generations that follow.

This article was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the October 2014 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.