The Piano’s Golden Age: How Schumann and Brahms Continued the Tradition

Schumann’s poetic lyricism and Brahms’ architectural mastery shaped the piano’s Golden Age. Their works expanded the instrument’s expressive range, blending Classical traditions with Romantic depth, ensuring that the piano remained a profound voice in musical history.

Few instruments in Western classical music have enjoyed as rich and transformative a history as the piano. From its early development in the 18th century to its dominance as a solo and ensemble instrument in the 19th, the piano became the medium through which composers expressed their most personal and profound artistic ideas. Among the towering figures of this era, Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms stand out for their contributions to the instrument’s legacy. Their works not only continued the traditions established by their predecessors—such as Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert—but also deepened the expressive possibilities of the piano, cementing their place in what is often referred to as the instrument’s “Golden Age.”

The Romantic Piano Tradition

By the early 19th century, the piano had undergone significant technological advancements, leading to greater dynamic range, sustain, and expressivity. Composers such as Beethoven and Schubert had already demonstrated its capacity for drama and introspection, pushing the instrument beyond its earlier role as a mere accompaniment tool for chamber music or vocal pieces. The increased resonance and improved action mechanisms of the piano allowed for more complex textures, richer harmonic explorations, and greater independence of voices—qualities that would become hallmarks of the Romantic piano style.

It was in this fertile environment that Robert Schumann (1810–1856) and Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) emerged as key figures in the continuation and evolution of the piano tradition. Both composers were deeply influenced by the past—Schumann idolised Schubert and Beethoven, while Brahms revered Johann Sebastian Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven—but each developed a unique voice that contributed to the instrument’s expressive range. Schumann, with his poetic imagination and highly personal language, expanded the piano’s narrative potential, while Brahms, with his structural mastery and rich harmonic language, synthesised past traditions with a forward-looking sensibility.

Robert Schumann: The Poet of the Piano

Schumann’s piano works are some of the most poetic and emotionally charged in the repertoire. Unlike composers such as Frédéric Chopin, who wrote almost exclusively for the piano, Schumann’s career encompassed orchestral, chamber, and vocal music. However, his early years were almost entirely dedicated to the instrument, producing a remarkable series of piano cycles that defined his distinctive voice.

One of Schumann’s most influential contributions to the piano tradition was his concept of the character piece. In collections such as Carnaval, Op. 9 and Kinderszenen, Op. 15, he created miniature musical portraits that convey moods, personalities, or scenes with extraordinary concision and emotional depth. These pieces often contained literary or autobiographical references, a reflection of Schumann’s dual passion for music and literature. Carnaval, for example, is a set of 21 pieces representing masked revellers at a festival, incorporating musical cryptograms and references to his beloved Clara Wieck. Kinderszenen (Scenes from Childhood) evokes childhood memories with remarkable tenderness, including the famous Träumerei, a piece of haunting simplicity.

Schumann’s piano writing is distinctive for its rich inner voices, syncopated rhythms, and innovative textures. Works such as Kreisleriana, Op. 16 and Fantasiestücke, Op. 12 showcase his ability to blend lyricism with impulsive, sometimes volatile shifts in mood—a reflection of his own psychological struggles. His Symphonic Etudes, Op. 13 and Fantasy in C, Op. 17 demonstrate his ambition to merge the virtuosic demands of the piano with symphonic grandeur, prefiguring Brahms’ later approach to large-scale piano writing.

Perhaps most significantly, Schumann’s piano music opened new possibilities for musical storytelling, blurring the lines between programmatic and absolute music. His works often suggest dreamlike narratives, full of contrast, mystery, and dramatic intensity, leaving room for the listener’s imagination to fill in the gaps.

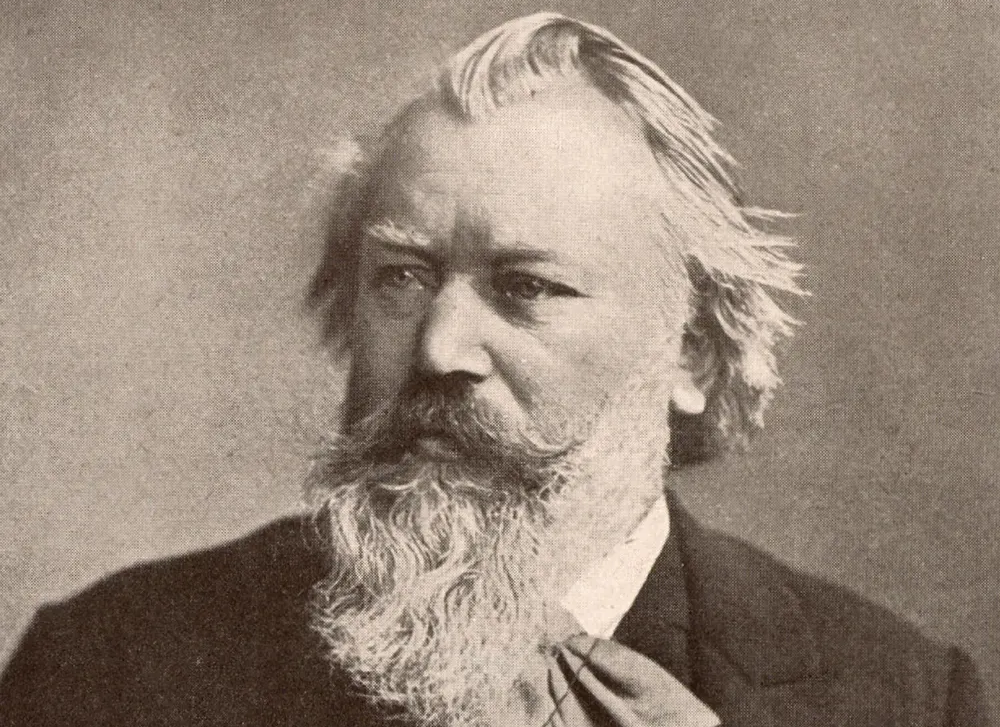

Johannes Brahms: The Architect of the Romantic Piano

If Schumann was the poet of the piano, Brahms was its architect. From the outset, Brahms displayed an affinity for counterpoint and form, drawing inspiration from Bach and Beethoven while maintaining a deeply personal Romantic sensibility. His piano works are characterised by structural solidity, complex rhythms, and a rich harmonic language that bridges Classical clarity with Romantic expressivity.

Brahms’ early piano works, such as the Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Op. 5, already demonstrate his ability to integrate Beethovenian drama with lyrical introspection. This sonata, the most ambitious of his three early sonatas, exhibits symphonic breadth and motivic development that reveal Brahms’ profound understanding of form. His Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel, Op. 24, exemplifies his deep respect for Baroque models, while his Paganini Variations, Op. 35, display his formidable technical command and ability to reinvent a theme through intricate transformations.

However, it is in his later piano works that Brahms reaches his most introspective and refined style. The Intermezzi, Rhapsodies, and Ballades of Opp. 76, 79, 116–119 contain some of his most personal and moving music. The late Intermezzi, in particular, possess an almost autumnal melancholy, distilling his harmonic richness and rhythmic subtlety into miniatures of profound depth. These pieces, far removed from the bravura of Liszt or Chopin, reflect Brahms’ inward-looking nature and his ability to express vast emotional landscapes with restrained yet powerful means.

Brahms’ approach to the piano was deeply rooted in textural density and rhythmic complexity. His left-hand voicings and contrapuntal textures create a sense of orchestral fullness, often giving the impression of multiple instruments within a single pianist’s hands.

Schumann and Brahms: A Musical Brotherhood

The connection between Schumann and Brahms extends beyond their individual contributions to the piano. When Brahms arrived in Düsseldorf in 1853, he was introduced to Schumann, who immediately recognised the young composer’s genius. In an article titled Neue Bahnen (“New Paths”), Schumann proclaimed Brahms as the future of German music, describing him as a composer destined to continue Beethoven’s legacy.

Brahms’ friendship with Clara Schumann was equally significant. A renowned pianist and composer in her own right, Clara played a crucial role in shaping both men’s artistic lives. She was one of the earliest champions of Brahms’ music, performing his works and offering guidance, while Brahms supported her after Robert Schumann’s mental decline and eventual death in 1856. This deep artistic and personal bond influenced Brahms’ compositional approach, particularly in his piano writing, which often contains echoes of Schumann’s lyricism and Clara’s pianistic style.

Continuing the Tradition

Schumann and Brahms, though distinct in their musical personalities, shared a commitment to upholding and evolving the great traditions of German music. Schumann’s deeply personal and literary approach expanded the piano’s ability to tell stories and evoke imagery, while Brahms’ mastery of structure and counterpoint ensured that the weight of the past remained a guiding force in Romantic music. Their works continue to hold a central place in the piano repertoire, inspiring generations of pianists and composers.