The Great Integrator

Satyajit Ray’s cinema was redolent of Indian and Western sensibilities. So was the music he loved, listened to, used in his movies and composed. By Manohar Parnerkar

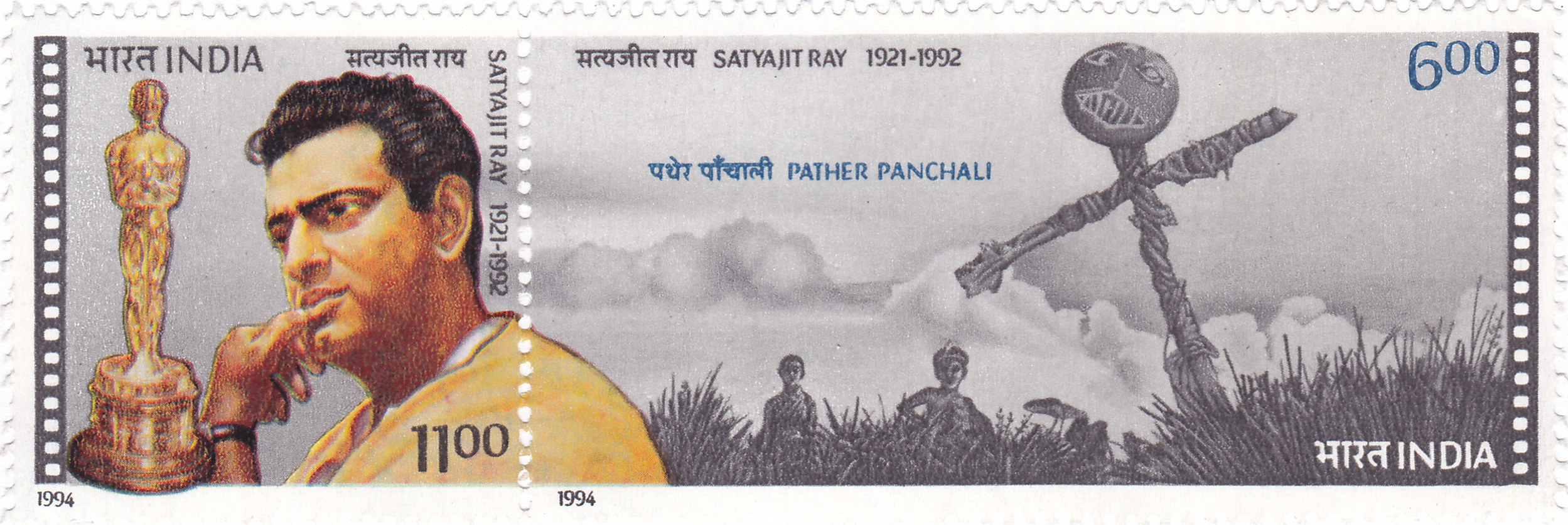

Satyajit Ray (1921-92), along with Sergei Eisenstein, Ingmar Bergman, Charles Chaplin, Federico Fellini and Akira Kurosawa, has been one of the giants of world cinema. He has also widely been considered to be India’s greatest filmmaker ever. And in an age of impoverished specialisation, Ray – this last of the titans of the Bengal Renaissance – was an artistic genius of staggering versatility. He was probably the most complete of the world-class filmmakers. He wrote his own scripts, composed his own film scores, edited his films, occasionally handled the camera, was an art director, illustrator, graphic artist, lyricist, and an outstanding adman and publisher. If this was not daunting enough, he also designed sets, costumes, credit titles and publicity material for his films. This fine neorealist auteur of India carried his dazzling versatility into the art and craft of film-making so masterfully that, on and off the film sets, he would often become a one-man film crew.

I have always felt that while Ray the filmmaker, has been comprehensively written about and universally celebrated, Ray the master composer somehow never quite seems to have received his due. With a few honourable exceptions, even film scholarship has not done justice to this brilliant facet of Ray’s versatile genius. This article is a tiny step in that direction.

A rich legacy

Ray’s cultural and artistic sensibilities were part Western and part Indian, though music-wise, he was often accused of being more Western than Indian. The filmmaker confessed nearly as much, when he told his biographer Andrew Robinson, “I am fifty-percent Western and fifty-percent Indian”. This fascinating duality of Ray’s artistic make-up can be traced largely to his family background.

Ray was born into a Brahmo family in Bengal, which boasted a remarkably broad cultural heritage and a deep interest in art, science, literature and music. A Bengali friend never tires of telling me that Brahmos were known to often sing the Psalms of David after chanting the Vedas. His gifted grandfather Upendrakishore Ray founded Sandesh – the iconic children’s magazine – and with Ray’s father Sukumar, edited it until their premature deaths. Rabindranath Tagore was a family friend who often came to visit the Ray home and induced Upendrakishore to play the violin, which he did brilliantly. In 1923, when Sukumar was virtually on his death bed, it was Tagore who sang nine of his joyful songs to him.

Ray was very fond of Indian classical music, Rabindra Sangeet and Bengali folk music, all of which he used extensively in his films. But what is not widely known is that he was vastly more knowledgeable in and passionate about Western classical music.

Ray had no formal music education of any kind, but he could carry a tune superbly by humming it or whistling it. He could also articulate his own musical ideas for his orchestra musicians on the piano which he played with ‘professional ease’. The sweet and soft piano accompaniment – chords and all – that you hear in the popular Kishore Kumar song ‘Ami Chini Go Chini’ from Charulata is played by Ray himself. He was endowed with a deep baritone voice in which he would often belt out, for close friends, Osmin’s aria from Mozart’s opera The Abduction from the Seraglio, or hum the songs of Papageno from the composer’s other opera, The Magic Flute or hum the Lacrimosa episode from Verdi’s Requiem. In his film Shakha Proshakha, it is Ray who actually hums the snippet from the first movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto which, on the screen, features the Beethoven-crazy character of Proshanto played by Soumitra Chatterjee. In Agantuk, the last feature film he made, Ray sang a keertan song reciting the different names of Lord Krishna.

The Beethoven factor

Ray’s lifelong love affair with Western classical music began when he heard a gramophone record of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in his maternal uncle’s house; he was then only nine or ten. The music so gripped him that later in life, he read whatever he could on, and heard whatever he could of, not just Beethoven’s life and music, but the essentials of Western classical music. His two-year stay at Santiniketan offered him an excellent opportunity to hear lots of Western classical music thanks to a German-Jewish professor of English who threw open his rich collection of it to him. During WWII, Ray and his wife Bijoya would often tune into Radio Berlin and listen to the music of Haydn and Bach. He had once received an offer from the BBC to make a documentary on Mozart’s opera, Don Giovanni which, for some reason, he could not accept. But this, nonetheless, was a solid recognition of his expertise in classical music at an international level.

Beethoven was Ray’s favourite composer. On top of the piano – a permanent fixture in his study – stood a bust of the composer. Mozart was a close second. But when it came to film music, he regarded the Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev as his guru. Ray made, in all, 36 films (29 feature films, five documentaries and two short films), and provided music for as many as 30 of them. In his early films, he worked with the three greats of the Hindustani classical music world: Ravi Shankar (The Apu Trilogy and Parash Pathar), Vilayat Khan (Jalsaghar) and Ali Akbar Khan (Devi). It must be noted that some of the most profoundly moving moments in Ray’s oeuvre are to be found in his first film Pather Panchali, and that they are owed entirely to Shankar’s marvellously expressive pastoral music.

However, post Devi (1960), Ray had become quite disenchanted with them. He had come to realise that professional musicians, particularly the prominent ones, could (or would) never bend their talents fully to the demands of a film. The fact that they also strongly resented being guided by him only aggravated the friction. And with each successive film, Ray was developing his own musical ideas, and now felt ready to take on the mantle of the music composer.

A rare breed

Among world-class filmmakers, only Ray and Chaplin were both director and composer of their films. But the fact that Ray, unlike Chaplin, could also read, write, notate, play (on the piano), sing, arrange, orchestrate and conduct music, easily makes him the rarest of this rare breed.

Ray once said, “If I were the only audience, I would not be using music.” He always felt that music was an extraneous element to film-making and that, ideally, a good filmmaker should be able to express himself without it. But being a hard-headed realist, Ray also knew that if he had to make the unusually subtle visual narratives of his artistic films accessible to the urban – even urbane – moviegoer, music was an absolute must. In his films, he employed this powerful aural tool most imaginatively and minimally, to a vastly greater effect. Ray also used stretches of utter silence and natural sounds (like, for example, a motorcar horn, a bird-song, the rustling of leaves etc.) with marvellous results.

A filmmaker needs music to deal firstly, with the vicissitudes experienced by the characters in the film’s story, and secondly, with the whole range of a character’s moods. Ray always felt that our music, which is essentially decorative in structure, could achieve beauty and even sublimity, but not drama, since it lacks conflict. Western classical music, on the other hand, can depart from the tonic or the shadja, and the resultant key changes, together with the device of the major and minor scales, lead to tremendous mood changes, which is perfect for conflict and drama.

The perfect score

In Shakha Proshakha, Ray makes the most liberal, and perhaps also the canniest use of the music of Bach and Beethoven. He employs it chiefly to portray the film’s two powerful, recurring themes. One is the despair of a large conflict-ridden Indian family of wealthy industrialist Anand Majumdar. And the second is the whole gamut of emotions and mood swings experienced by Proshanto, Majumdar’s brain-damaged son, who has taken refuge in Western classical music. One of the high points of the film has Proshanto listening to the Gregorian chant ‘Kyrie Eleison’, which almost seems to echo the thought that only the Lord can heal the wounded family. In Ray’s 1958 film Jalsaghar, there is a scene where protagonist Biswambhar Roy is gripped by his own impending doom at the sight of the darkening chandeliers. Ray felt Khan’s sitar music alone – no matter how soulful – would not be able to convey Roy’s terror. To achieve the desired sound texture, he reinforced Khan’s music with notes by Finnish composer Jean Sibelius, played backwards. Incredibly, Ray modelled the basic structure of his 1964 film classic Charulata on Mozart’s great String Quintet in G minor. The five characters in the film’s tragic story are represented by the sounds of five string instruments, namely, two violins, two violas and a cello, with their contrasting tonality and dialogue.

In an interview, Ray once said, “I mix European and Eastern and our Oriental music because our lifestyle is a mixture, anyway…If you use purely classical Indian music in films, which are for instance, contemporary in theme and look – urban contemporary – it doesn’t sound right.” I think it is safe to say, he was completely right.

This piece was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the June 2019 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.