The Goan contribution to classical music

India’s classical music legend Maestro Zubin Mehta turned 85 this year, on 29 April. A grand concert was organized by his long-time friend, pianist Daniel Barenboim, featuring the orchestra of the Staatskapelle Berlin (of which Mehta in honorary conductor) at Staatsoper Unten den Linden. It was conducted by Mehta himself (seated rather than standing, following surgeries to both knees) and included Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto (with Barenboim as soloist) and Schubert’s Symphony No. 9 (“The Great”) in C Major,

The concert was broadcast online for free, but due to the time difference, I opted to listen to it a little later, albeit within 24 hours. I would realize later how fortunate I was, as it was inaccessible after that outside Europe.

It goes without saying what a great fan I am of his; my first experience of a live world-class orchestra was in the 1980s (it was the reward I begged of my parents when I got a state rank in the 12th board exam in Goa) at Shanmukhananda hall for his historic visit with the New York Philharmonic, its first and only tour of India. Since then (barring my decade away in the UK) I’ve attended most of his Mumbai concerts through the decades, trekking sometimes twice from Goa to Mumbai, once to procure a ticket (even spending the night on the pavement on one memorable occasion, sharing chai and beedis with the drivers and other staff standing in for their wealthy bosses who were too posh to stand in line themselves), and then returning again for the concert(s).

I read an interview Maestro Mehta gave to the Corriere della Sera earlier that month. (“Zubin Mehta reflects on a life in music on the eve of his 85th birthday”).

He shared his thoughts about Florence (the city in which he was being interviewed) and his almost six-decade long connection with it; his long and close association with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra; conducting Turandot (which was filmed live) on location in the Forbidden City; his health issues and more.

He reminisced on his early years before arriving in Vienna in 1954 from India for the first time. Regarding his musical experience prior to that, he summed it up in this one sentence: “I had grown up in Bombay with an orchestra of amateurs: the brass from the Navy band played in uniform, and the strings were Parsis (my religion) and amateur Jewish refugees.”

Do those of you who lived through or read about music life in the Bombay of the 1950s or even earlier notice a glaring omission? You guessed right: the Goan musician.

From my own experience with the press, I know first-hand that quite often one ends up getting misquoted in interviews, or that one’s quotes get trimmed to fit a pre-determined word count. It’s also possible that the journalist or the editing staff only kept references that they felt were relevant to their readership. A reference to Goa or Goans would then need some explanation and context, which might have seemed like a digression given the larger picture of Mehta’s long and illustrious life in music.

Whatever the reason, the omission is unfortunate. It only compounds the invisibilisation of a community that has played such an instrumental (if you’ll pardon the pun) role in the history of music and music-making in not just Bombay/Mumbai, but in the rest of India and further afield. Whatever does get written or documented on the subject is largely within the Goan diaspora. Recently, Goa-based projects and festivals have begun to address this, and even then, it has focused largely on film music or jazz. It would be nice if the recognition were a little broader, even when it comes to classical music.

Edward Behr, “a German citizen educated at the Royal College of Music London” who at the time was conductor of the Governor’s Band and leader of many light opera productions in Bombay wrote a letter to the Times of India in June 1920 elaborating his idea of commencing a symphony orchestra: “….the orchestra would be for the people, it should be of the people also – that it should consist of Indians: Mahomedans, Hindus, Parsis, Goanese, Anglo-Indians, in short, of any musical talent to be found in this country strengthened by capable European players in different sections of the band.” It would become the city’s first orchestral initiative, the Bombay Symphony Orchestra.

In 1935, a newspaper reported that the orchestra, “in which Parsis, Muslims, Hindus, Goans, Hungarians, Frenchmen, Germans, Austrians and Englishmen combine to produce harmony”, made it “the most cosmopolitan orchestra in the world.”

Note the term Goan(ese) being mentioned as an entity open to interpretation, representing a faith (Catholic) as well place of origin (Goa). But due admission of their contribution was made then.

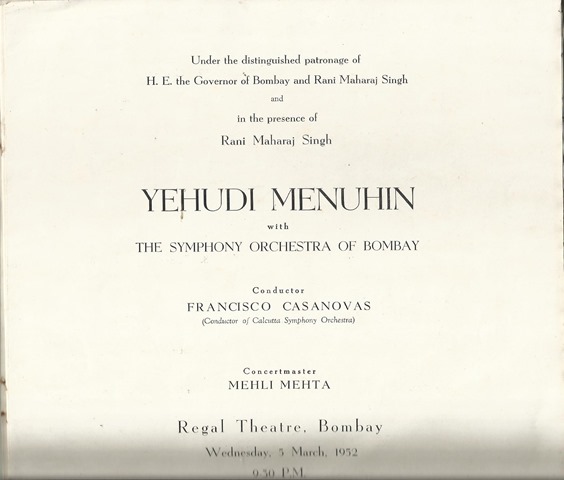

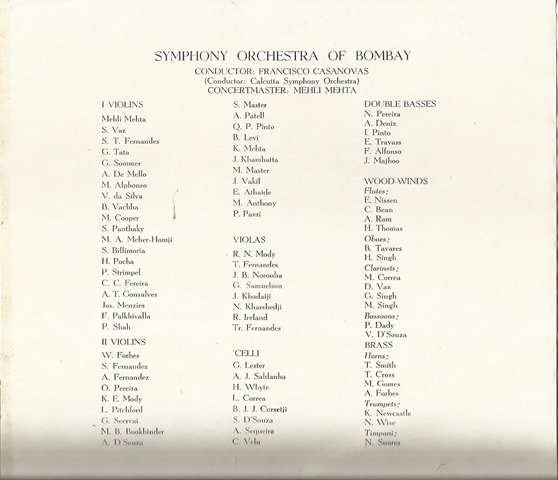

I have the roster of the musicians of the Symphony Orchestra of Bombay that played at the Regal cinema theatre on Wednesday, 3 March 1952. It was a gala concert that had the great violinist Yehudi Menuhin as guest soloist. (Incredibly, that night, he performed two (!) violin concertos, the Mendelssohn E minor and the Beethoven, separated by the mighty Chaconne from Johann Sebastian Bach’s D minor Partita for solo violin). The list of names in the orchestra reads like a Who’s Who of great instrumentalists of their age and of not just Goan but India’s music history.

Incidentally the concertmaster at that concert was Zubin Mehta’s father Mehli Mehta. And I have it on authority from eyewitnesses to rehearsals to that concert that a not-yet-sixteen Zubin conducted some of the orchestra rehearsal sessions.

Maestro Mehta has gone from that teenage initiation to unimaginable heights since then, but I’m sure that formative memory persists. At that concert, Goan musicians comprised 37% of the string section, and 40% of the tutti (entire orchestra), a significant percentage. The Parsi contribution to the tutti was 25%. The Jewish refugee percentage is a little more difficult to ascertain.

I believe this snapshot is pretty representative. In my own experience, I came across so many Goan musicians from the ‘old guard’ who had been on Bombay’s (and some even in Calcutta and further afield; Karachi, Rangoon, Malaya) orchestral circuit. Off the top of my head, there was my own violin teacher, Carlos D’Costa, but there were so many others, too numerous to mention.

Many of these musicians (often out of necessity, to earn a living) were equally at home in film recording studio, a jazz club, a swing band in a glitzy five-star hotel, or at a Concanim tiatr.

To get an idea of the quality of the string-playing they were capable of, just listen to the soundtrack of the song ‘Molbailo Dou’ from the 1963 landmark Concanim film ‘Amchem Noxib’. I wish I knew the names of those in the studio for that song (and also who composed the song and its string-writing; we know its lyricist was C. Alvares and it was sung by Molly). Despite all the gimmickry of technology in recording studios today, that lush, rich, exuberant string sound still is in a class apart.

The Goan contribution in both the existing orchestras in Mumbai, the Bombay Chamber Orchestra and the Symphony Orchestra of India (SOI), continue to this day. The last time I attended an SOI concert, Goan musicians made up almost 50% of the Indian musicians in an orchestra largely dominated by Kazakh musicians.

Among the many reasons I loved watching Bardroy Barreto’s 2015 ‘Nachom-ia Kumpasar’ was its salute to the unsung Goan musicians and their contribution to the Hindi film industry and to music in general. They created history but have been airbrushed out of it. The comment at the end of the film was particularly hard-hitting: “After a final flourish in the 70s, the curtains slowly came down. There was no finale. No calls for an encore. And no applause.”

There still isn’t applause, but let there at least be acknowledgement of the Goan contribution to classical music.

This article first appeared in The Navhind Times, Goa, India.