The Enigmatic Schumann: Insights from Steven Isserlis’ Performance Journey

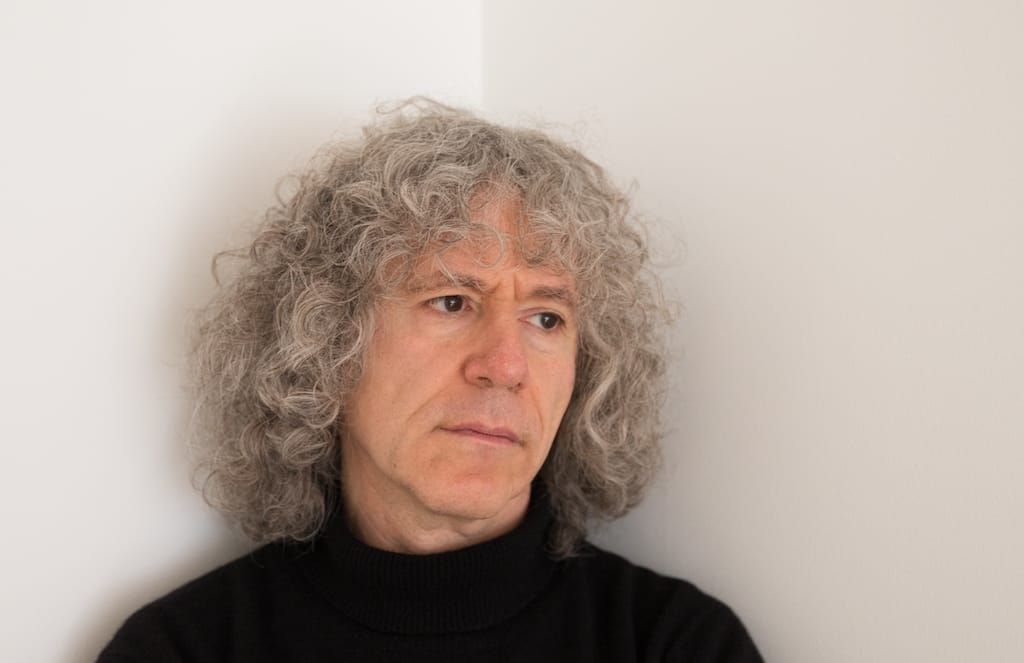

The acclaimed British contemporary cellist Steven Isserlis is also passionate about music education for children. During my England years, much before I became a father myself or was even contemplating beginning a music education charity for children (incidentally, both my son and Child’s Play India Foundation were born the same year, which makes it convenient to remember milestone years for both!), I purchased both of his books for children: ‘Why Beethoven Threw the Stew’ (Faber, 2001), and ‘Why Handel Waggled His Wig’ (Faber, 2006). I guess they spoke to the child still in me.

That was my first introduction to Isserlis’ witty, frequently self-deprecating writing style. Since then, I avidly read his articles on his website that range from composers to performers, matters of interpretation, form in performance, practicing, learning a new work and other issues. His social media posts are fun to follow as well.

Reading Isserlis, his adulation of the great Romantic composer Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856) quickly becomes obvious. In the first children’s book, “the shy Schumann” is among the six composers, and Isserlis calls him his “hero of heroes.”

In 2016, he published ‘Robert Schumann’s Advice to Young Musicians Revisited by Steven Isserlis’ targeted to music students. I heartily recommend all three books; they’re written from the heart and a delight to read.

Almost three decades ago, in 1996 he was writer and presenter of a documentary, ‘Schumann’s Lost Romance’, billed as “a musical detective story” in which he investigates the final years of Schumann’s life. Although the ‘lost romance’ refers to the five pieces for cello and piano that Robert’s wife Clara Schumann destroyed among many other “late” works thought to be “tainted by his madness”, the film closely examines Schumann’s Cello Concerto in A minor, Op. 129, also a relatively “late” composition, written in a creative burst six years before his death. He would not live to hear its first performance which only took place in 1860, four years after he died.

In a recent interview, Isserlis called it,

“the concerto I play most often, such a magical masterpiece, every note perfect. The first movement is a real journey of the soul, opening with a love song, travelling to dark regions in the central section, and then returning to love. The slow movement is a glimpse of paradise, the last an outpouring of joy.”

For all these reasons, when I read in the autumn season programme of the Symphony Orchestra of India (SOI) that Isserlis would be performing that same work, (and under the baton of British-Indian conductor Alpesh Chauhan, whose debut with the SOI I had missed last year as it clashed with a Child’s Play event here), I knew I had to go.

To add to the allure, it was a very interesting programme: the Schumann concerto was preceded by the orchestral suite (1945) from Richard Strauss’ 1911 comic opera ‘Der Rosenkavalier’ (the Knight of the Rose, or the Rose-Bearer), which brims over with some of the most ravishing music ever written.

The second half of the programme was given over to Igor Stravinsky’s “timeless tragedy of the human spirit”, the 1947 version of his landmark ballet ‘Petrushka’.

Both the outer works require gargantuan orchestral forces compared to the Schumann. ‘Petrushka’ in particular with its vivid programme imagery in four tableaux narrating the love triangle between the eponymous puppet, the Ballerina and the Moor would put any orchestra through its paces.

I was able to sit in at the SOI rehearsal the afternoon before the concert. Watching and listening to a professional orchestra rehearse is always a hugely educational experience. Chauhan tweaked segments of the Rosenkavalier and Petrushka in the first half of the rehearsal, on one occasion leaping over the flower-bedecked edge of the stage into the auditorium to hear for himself the balance between the orchestral forces in the signature ‘Presentation of the Rose’ (a series of ‘magical’ shimmering chords played by flutes, solo violins, harps, and celesta) scene from the Rosenkavalier.

The rest of the rehearsal was devoted to a straight play-through of the Schumann concerto. Isserlis plays the 1726 ‘Marquis de Corberon’ Stradivarius, (on loan from the Royal Academy of Music) and uses gut strings for their “warmer and mellower tone quality.”

The ‘Marquis de Corberon’ is one of the last cellos to have been made on Stradivari’s Forma B mould, which defined the outline shape of many of Stradivari’s most famous cellos from 1709 onwards, coinciding with the ‘golden’ period of Stradivari workshop production. It was crafted during lean economic times, warranting the use of locally grown willow wood for the back and ribs and the dark red brown varnish. But it is the one-piece willow back that projects its sound very well in the concert hall. Although willow sounds softer than maple, it produces “an extra depth of colour and darkness of tone without sacrificing core sound.”

One got a glimpse of the Isserlis brand of humour when an orchestra cellist asked to try out his Strad. Isserlis relented, but later said, “I don’t usually do this, you know. It’s like being asked for permission to kiss your wife!”

At rehearsal and in concert, Isserlis seemed bodily immersed in the music, even in the orchestral interludes.

His encore piece was apt, a meditative paean to freedom: ‘Song of the Birds’ (El cant dels ocells), a Catalonian folksong made famous by the great cellist Pablo Casals (in a version for solo cello arranged by Sally Beamish).

Writing about Schumann’s music in his first book, Isserlis says: “To speak very generally, I would say that Bach’s music shows us God’s view of the world; Mozart’s music is like a part of nature; Beethoven speaks for all mankind; and Schumann? Schumann’s music tells us what it was like to be Robert Schumann, and yet it still speaks to us, because his emotions were so strong, so real, that we can recognise ourselves in him. Everything that he experienced in his life comes pouring through his music; there is no composer whom we get to know as intimately as we get to know him. He tells us his deepest secrets, shares with us his most private dreams – in fact he talks to his listeners as if we were his most beloved friends.”

In the book and the documentary, Isserlis refers to the sudden, seemingly coming-out-of-nowhere ‘falling fifth’ in the cello concerto’s second movement as Schumann’s “personal message” to his beloved wife Clara, something he did in many guises in so many of his compositions.

In many ways, romantic love was the unifying theme in this thoroughly engaging SOI concert, whether it was encoded in the composition (as in the Schumann) a celebration of it or coming to terms with its ebb or loss.

This article first appeared in The Navhind Times, Goa, India.