The Curse of the Ninth Symphony: Why Did So Many Composers Stop at Nine?

The "Curse of the Ninth" haunts classical music folklore, with great composers seemingly doomed after completing nine symphonies. But is it fate, superstition, or simply the natural arc of creative life?

In the world of classical music, few legends are as enduring—or as eerie—as the so-called "Curse of the Ninth Symphony". The idea that composers are somehow doomed after completing their ninth symphony has haunted musicians and fascinated listeners for generations. But where does this superstition come from? And why did so many of the great composers seem to stop at nine?

The Origins of the Curse

The notion of the curse traces back primarily to the towering figure of Ludwig van Beethoven. Beethoven, whose influence on Western music is immeasurable, completed nine symphonies before his death in 1827. His Ninth Symphony—often hailed as one of the greatest pieces of music ever written, with its rapturous choral finale setting Friedrich Schiller’s "Ode to Joy"—was a monumental achievement. Yet, Beethoven never lived to attempt a tenth.

Beethoven’s death after his ninth symphony planted a seed of superstition that grew stronger over the following decades. When subsequent composers also seemed unable to surpass the number nine, a pattern was perceived, whether by coincidence or something more mysterious.

Mahler and the Formalisation of the Curse

The most famous proponent—or perhaps, victim—of the curse was Gustav Mahler. Deeply aware of Beethoven’s legacy, Mahler was intensely superstitious. He believed that attempting to write a "tenth" symphony could tempt fate. To outwit the supposed curse, Mahler composed a work titled Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), a symphonic song cycle that, while effectively a symphony in all but name, allowed him to avoid numbering it as his ninth.

Following this, he proceeded to compose his actual Ninth Symphony. Tragically, Mahler died while working on his Tenth. Though he left sketches and drafts, the symphony remained unfinished at his death in 1911. To many, this seemed like a grim confirmation of the curse’s reality.

Mahler’s death at the threshold of his tenth symphony gave weight to the superstition, and later generations of composers would remain uneasily aware of it.

Other Composers and the Number Nine

Several other significant composers also seemed unable to pass the nine-symphony mark:

- Franz Schubert: Died young, at only 31, after completing what is now known as his "Great" Ninth Symphony. He had begun work on additional symphonies, but they were left incomplete at his death.

- Anton Bruckner: A fervent admirer of Beethoven, Bruckner struggled with his Ninth Symphony until his death in 1896. The work was unfinished, though his three completed movements are often performed today.

- Antonín Dvořák: Composed nine symphonies, with his last—famously subtitled From the New World—becoming one of the most beloved symphonic works. He lived for a few more years after its completion but never produced a tenth.

- Ralph Vaughan Williams: Though he completed his Ninth Symphony shortly before his death in 1958, he had not begun a tenth, again seeming to affirm the pattern.

In each case, the composers either died shortly after completing their ninth symphony or failed to complete a tenth, reinforcing the mystique around the number nine.

The Power of Myth

Of course, not all composers succumbed to the "curse". Dmitri Shostakovich wrote 15 symphonies, as did his Soviet contemporary Nikolai Myaskovsky. Malcolm Arnold composed nine and lived for many years thereafter, though he did not venture into a tenth. Similarly, other composers like Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, while prolific, were not confined by symphonic numbering in quite the same way, given the evolving form of the symphony during their lifetimes.

Yet the persistence of the curse in musical folklore is telling. Classical music, with its reverence for tradition and mythology, naturally lends itself to such stories. The number nine, seen in other cultural contexts as symbolic of completion or finality, takes on an almost mystical weight when paired with music’s most ambitious form—the symphony.

Symphonies and Mortality

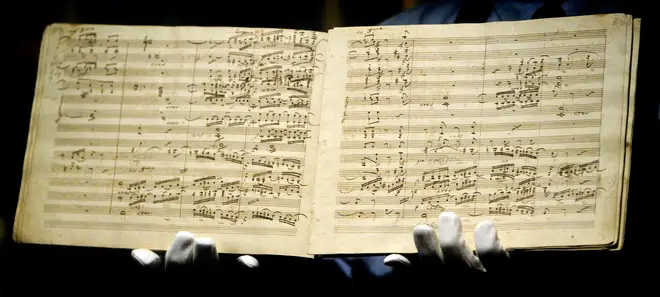

There is also a more pragmatic explanation for the phenomenon. Writing a symphony—particularly after Beethoven—became an almost impossibly daunting task. After Beethoven revolutionised the form, a composer who dared to write a symphony entered into a dialogue with all that had come before. Each symphony was expected to be a statement, a monumental work of artistic purpose.

For composers like Mahler or Bruckner, each symphony was not merely a musical endeavour but a profound philosophical and spiritual undertaking. As such, by the time a composer had completed nine symphonies, they were often advanced in age, their health weakened by the emotional and intellectual toll of their life’s work. Death following the ninth could thus be seen as inevitable, rather than mystical.

Moreover, the effort to outdo the previous works—to make each symphony more expansive, more emotionally encompassing—meant that symphonies grew longer and more complex over time. The demands of the form grew heavier, making it harder for composers to produce multiple late works.

The Modern Perspective

Today, the "Curse of the Ninth" is more of an amusing piece of musical folklore than a genuine concern for composers. In the 20th and 21st centuries, many composers have either shrugged off the superstition or moved beyond the traditional symphonic format altogether.

Philip Glass, for instance, has written twelve symphonies (as of 2024) without incident. Similarly, the American composer David Maslanka completed ten symphonies before his death, seemingly unaffected by the curse.

Nonetheless, the legend continues to fascinate because it touches on larger themes: the relationship between art and mortality, the idea of creative exhaustion, and the notion of finality in a composer’s output. There is something poetic—something tragically fitting—about the idea that the symphony, that grandest of musical statements, might serve as an artist’s final word.

Conclusion

In truth, the Curse of the Ninth is less a real phenomenon than a romantic illusion. It reflects the natural course of human life and artistic endeavour rather than any supernatural fate. Yet the story endures because it speaks to our love of myth-making, our tendency to seek patterns in chaos, and our awe before the great figures of music history. When we hear Beethoven’s Ninth, or Mahler’s, or Bruckner’s unfinished work, we are listening not only to masterpieces but also to human beings grappling with their own mortality.