Teaching Students to Pedal, Part 4: Introducing Debussy’s Pedal Indications

Pedalling is essential to creating the magical sounds called for in the piano music of Debussy. The moods, atmospheres, and far-off lands he conjured cannot be evoked without skilful use of both the sustaining and the una corda pedals. In my experience students respond very positively to this music once they are taught to search for Debussy’s very clear indications of when to engage and also to release these pedals.

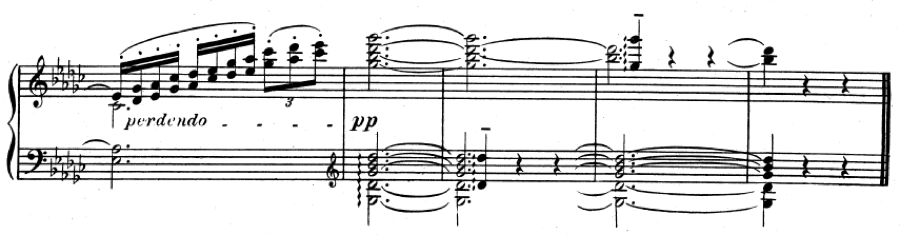

Debussy very rarely employed the “Ped.” indication that was introduced by Beethoven and was extensively employed by Chopin. In the Children’s Corner suite we only find this notation once:

Similarly, in the first volume of Preludes we only find this indication a single time, at the end of Voiles:

In both instances he is requesting that we keep the pedal down while removing our hands from the keys, either in response to the rests in the first example, or the commas in the second. Elsewhere in his piano music he developed a more subtle and precise way to indicate when he wanted the pedal employed and for exactly how long.

In the following example, from the popular Prelude, The Girl with the Flaxen Hair, the rolled G-flat Major chord that finishes the piece is tied through the final measures. The hands must release the chord in order to play the broken octaves that come afterward, but the pedal must remain depressed in order to sustain the chord. There was no need for Debussy to write “Ped.” as the continued sound of the chord necessitates the pedal. The fingers cannot hold the notes, so the pedal must.

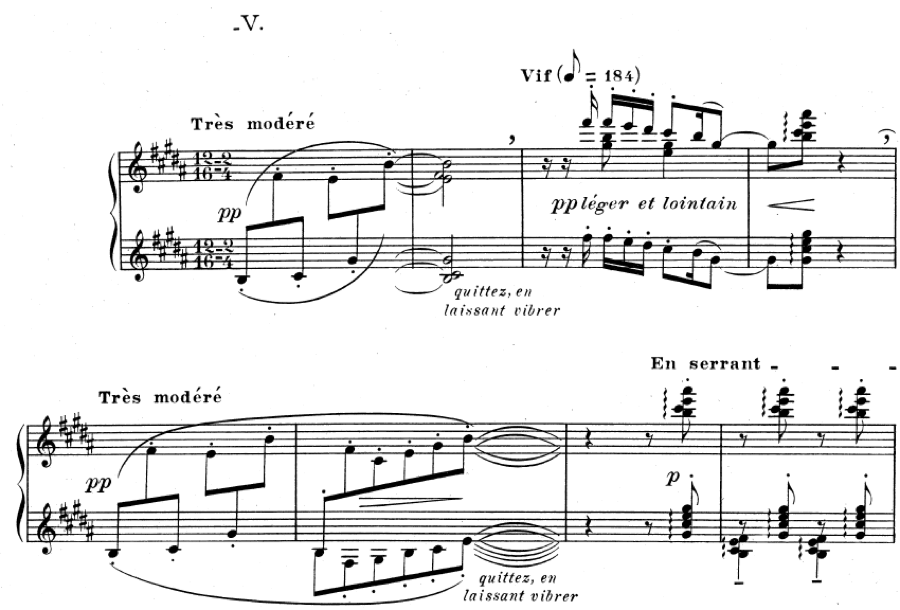

In the following example from Preludes, Book 1, we again see ties from the first measure into the second. Debussy uses words to clarify what we are to do: “quittez, en laissant vibrer,” meaning leave, or release the keys, but allow the sounds to vibrate, or resonate in the pedal. On the second line he doesn’t even feel the need to write out the notes that are being sustained in the second measure and just puts the ties. He continued to use these ties to empty space throughout his piano music and it has become a standard notational practice since then.

This same example was shown in the previous article in this series to illustrate the portato touch, where composers wrote both slurs and dots over a series of notes indicating to play with a separate touch but to use pedal to sustain the sound. Another example of the portato notation is found at the very beginning of the first Prelude from Book 1:

This notation is found throughout Debussy’s piano music and should be explained to students as another way the composer requested we engage the sustaining pedal.

In the following example we see a case where Debussy used his original tie notation to indicate subtle but important clues. All of the notes in the first measure are followed by ties, indicating they should all be in the same, long pedal that starts at the beginning of the measure. These notes all continue across the bar line into the following measure, meaning that the rests at the beginning of the second measure are indications for our hands to leave the keys but for the pedal to sustain the sound through the rest. “Quittez, en laissant vibrer” once again. In the middle of the second measure we see something different: rests with no ties. My understanding of this moment is that the pedal should release for these rests, creating a breath in the music. Teaching our students to distinguish these moments will help them come to understand this music.

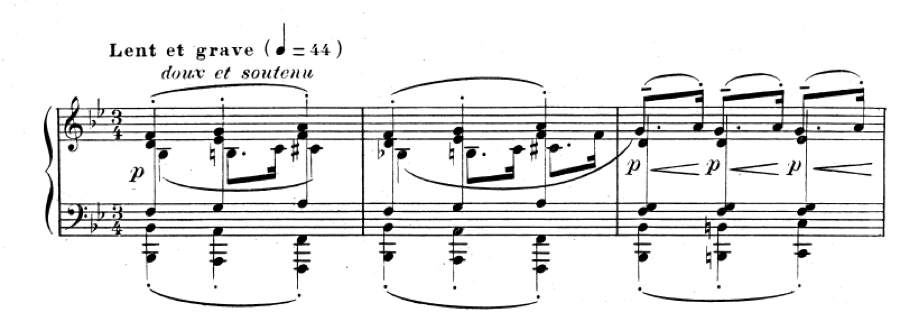

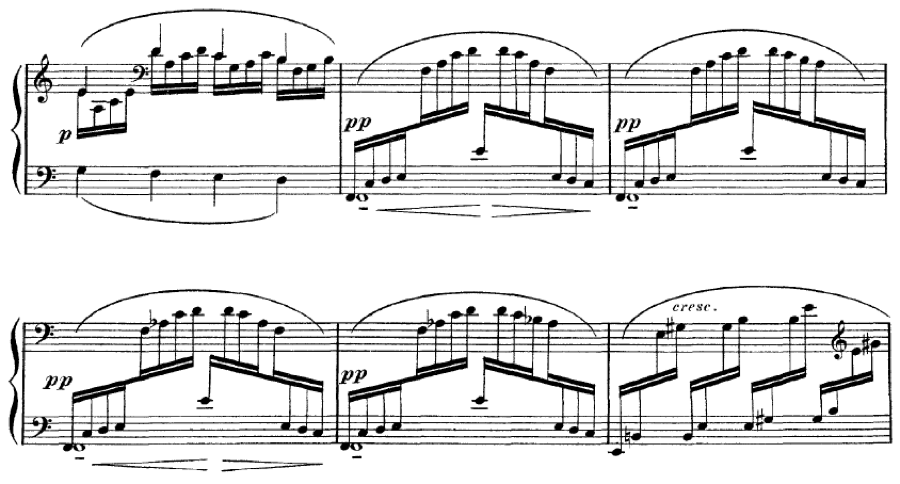

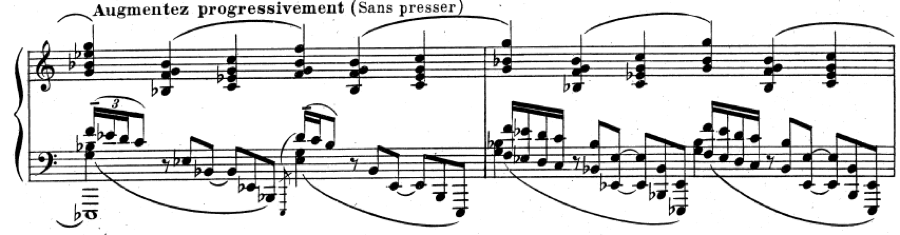

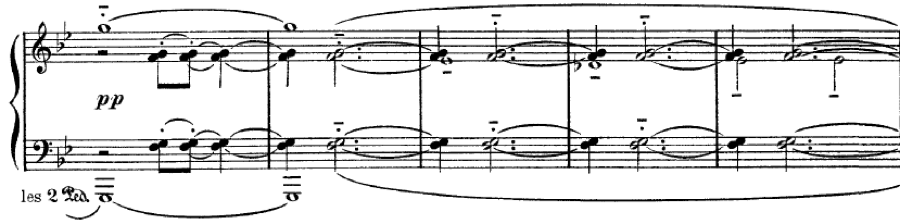

Other issues we must show our students are sustained notes without ties that can only be held for the indicated length by using the pedal. Here is an example from Dr. Gradus ad Parnassum, from the Children’s Corner suite:

In the second measure Debussy writes a whole-note F in the bass. In the middle of the measure the left hand is asked to cross over the right to play the higher E. The left hand is required to release the F in order to move, so Debussy is asking us to retain the pedal for the entire measure.

He then varies this later in the piece by having a whole-note bass in the first measure of the following example, but then half notes, asking us to change the pedal twice per measure instead of only once.

Notice that in the second measure Debussy not only writes a half note for the bass E, but then a half rest, indicating he wants that E to finish. This can only be accomplished by changing or releasing the pedal. The rest, in my understanding, does not mean we cannot pedal, but only that the sound of the E must be ended. We can have a new pedal there if we wish; we just can’t continue hearing the bass E.

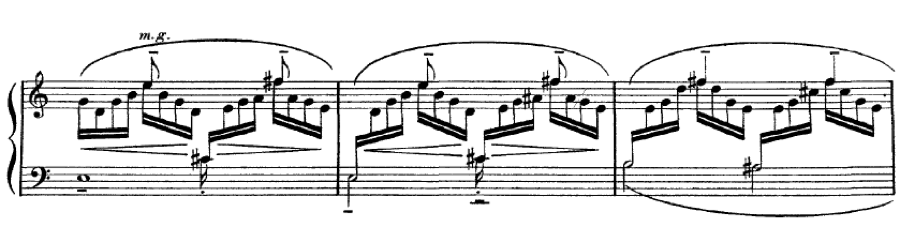

Further along in the same piece we get this beautiful passage:

Again, the basses must be sustained with the pedal, since the left hand is also asked to play notes in a different register.

After all this attention to long notes that are sustained we might think that all long notes must be pedalled. It isn’t always the case. If they can be held with the hands then that may be the desired effect, as it creates a contrast between sustained notes and short staccatos.

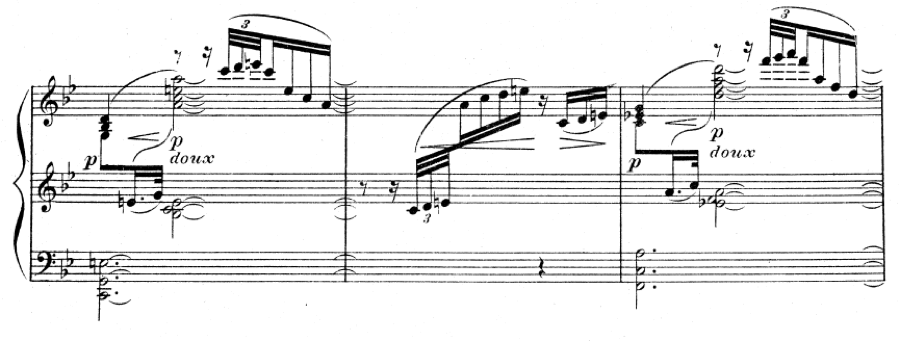

Here is a moment that creates confusion for students but can actually be used to help clarify the principles we’ve been discussing:

The first measure of the second line begins with half notes in both hands. Pedal must be used to sustain these for exactly the two counts indicated. There are no ties, so the rest at the beginning of the next measure should be observed by the hands as well as the foot. The staccato chords of the second measure should be played without pedal, since there is no indication otherwise. The chords with grace notes of the second measure look the same as the ones in the first measure, but will sound different because there is no pedalled chord starting that measure.

There are examples where Debussy wants a very long, sustained bass, but with so many notes above that using a single pedal would create a confused sound. In this example from The Sunken Cathedral, the E-flat in the bass is written as a whole note in the first measure. Keeping a single pedal for the entire measure would cause the many notes above to accumulate. A choice I make is to retake the pedal each time the bass note returns, honouring Debussy’s request that the E-flat be sustained, but allowing the listener to distinguish the melodies above more clearly.

Students often resist long pedals because they’re not accustomed to hearing so many sounds at once. We need to help them find the correct balance amongst all the different voices so that they discover the special sound world Debussy created. Stronger basses, clearer melodies, and lighter accompaniments are often required. As always, careful listening is the most important tool.

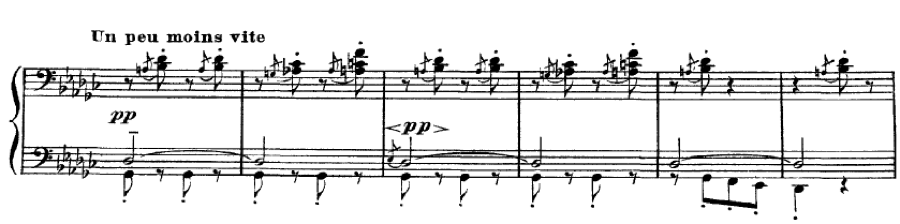

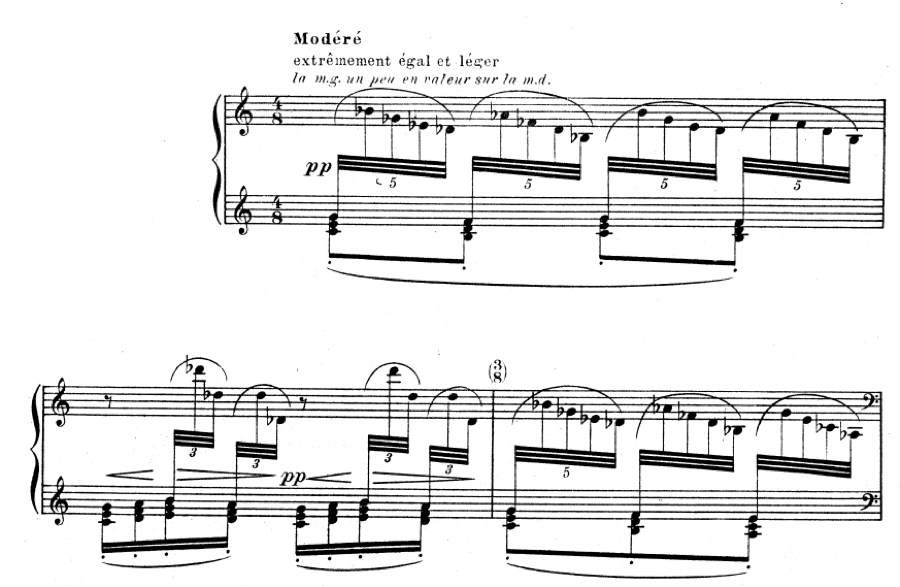

A complicated topic is whether the pedal needs to be depressed fully to achieve a desired effect. The following example has no bass note that would help our ear to organise around a harmonic center:

The title of this prelude means “fog,” so some blending of sounds is desirable, and pedal is requested by means of the portato notation in the left hand. But a single, long pedal wouldn’t allow the listener to distinguish any of the materials used in this piece. In this instance I recommend a shallow pedal, meaning one where the foot is not depressed all the way to the bottom, and that the foot gently rise so as to release some but not all of the sound regularly.

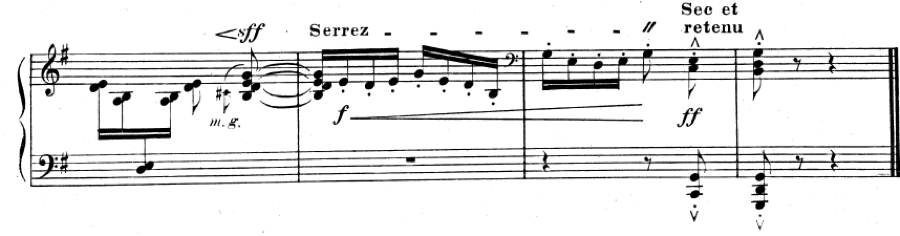

Debussy was generous in indicating the lengths of pedals he wanted. He would also let us know when he didn’t want pedal by using the word “sec,” or “dry.”

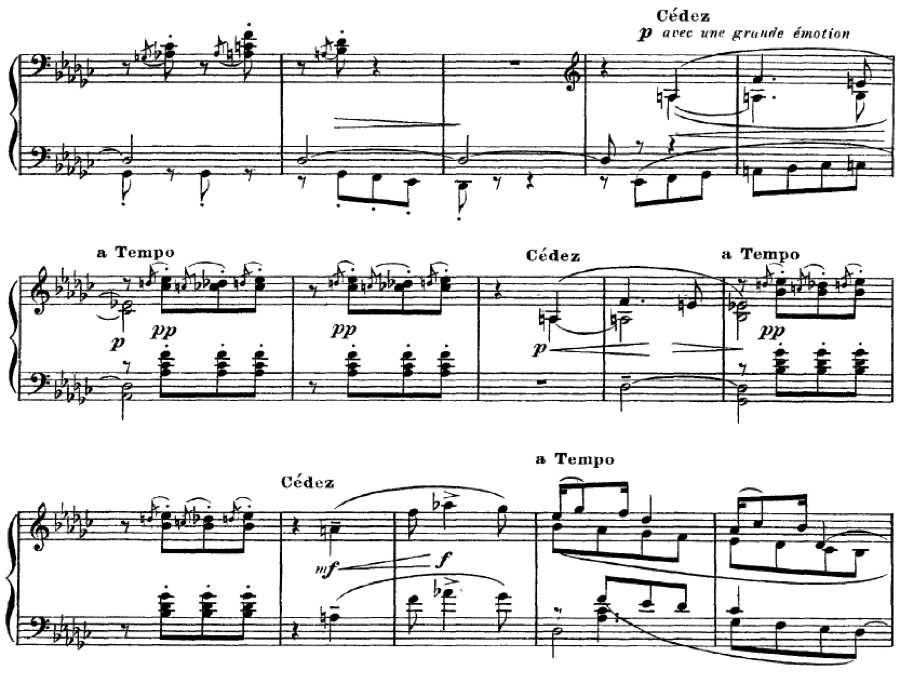

The una corda, or left pedal, is also important in creating the sound Debussy requested. He wrote about wanting the piano to sound like a string instrument, free from percussion. Using the una corda pedal helped achieve this sound. The indication at the beginning of the Serenade for the Doll is instructive:

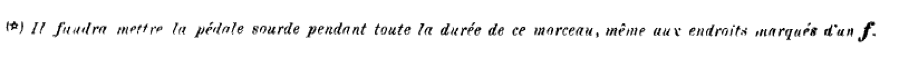

“It will be necessary to use the soft pedal during the entire length of this piece, even in places marked f.” The use of the soft pedal was not for Debussy a matter of volume as much as a way to achieve a different quality of sound. The una corda pedal on a grand piano shifts the entire action to one side. One result is that the hammers then strike two of the three strings on treble notes (though on earlier pianos they could shift far enough to strike only one string, or una corda in Italian). Another result is that the hardened felt that usually strikes the strings is shifted over so that the less-used, softer felt is then in position to strike the strings. The strings that are not being struck are vibrating sympathetically, creating a quality of sound that can’t be replicated by any amount of finger control.

The una corda pedal was one of only two pedals on French pianos of this time, so in places where Debussy wanted both the sustaining and the una corda pedals used he employed this indication:

Asking for both pedals meant using the soft pedal in addition to the sustaining pedal.

Introducing the music of Debussy to our students can be challenging because of how different the style is from the music of earlier periods. We must teach them what the notational signs all mean, we must help them translate all the directions given in French, and we must train their ears to listen for brand new sounds. My experience has always been that these new sounds spark their imagination and inspire them to listen to all their pieces in new and more discriminating ways. Our ultimate goal is to engage and train our students’ ears as well as their hands. This music offers us an opportunity to greatly expand their capacities.