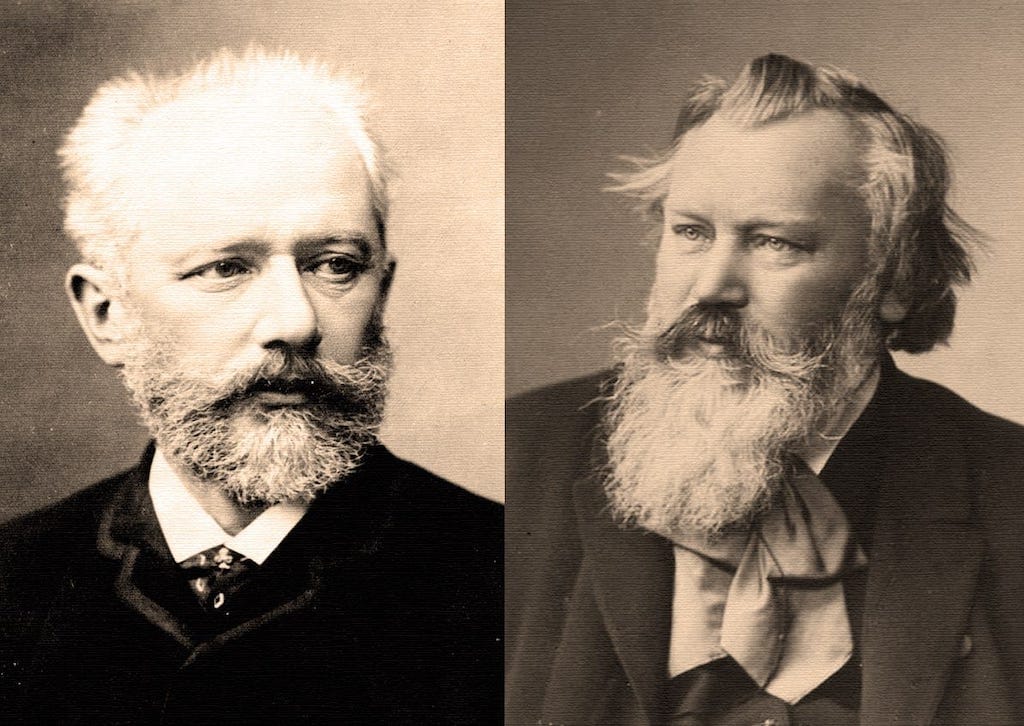

Tchaikovsky and Brahms: Respect Amidst Differences

Tchaikovsky’s passion and Brahms’s restraint reveal contrasting Romantic ideals. Their respectful tension highlights 19th-century music’s diversity, where opposing styles coexisted, each enriching classical tradition through unique approaches to emotional and structural expression.

The late 19th century was a period of intense musical development, with composers pushing boundaries and defining new directions for classical music. Among the towering figures of this era were Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Johannes Brahms—two composers often seen as polar opposites, both musically and temperamentally. While Tchaikovsky was known for his emotive, melodically driven works, Brahms represented a more formal, intellectual approach to composition, rooted in classical structures. Despite their stark contrasts, the two men shared a nuanced respect for each other's work, leading to a complex relationship marked by both admiration and tension.

Diverging Musical Ideals

Tchaikovsky and Brahms were products of different musical traditions. Tchaikovsky, as a Russian composer, was deeply influenced by the Romanticism sweeping through Europe, yet he maintained a distinctive Russian sensibility. His music often carried an emotional intensity, a dramatic flair, and a commitment to melody that drew on Russian folk elements and the intense inner landscapes he sought to express.

In contrast, Brahms was considered a conservative figure in the German Romantic tradition, often labeled as the true heir of Beethoven. His compositions relied on formal structures and thematic development, epitomized by his commitment to counterpoint, variation, and restraint. Brahms sought to balance innovation with homage to the past, creating music that resonated deeply with intellectual clarity but eschewed overt sentimentality.

This divergence in musical language and philosophy positioned them on opposite ends of a spectrum that defined Romantic music, placing Brahms closer to the more structured traditions and Tchaikovsky towards a more expressive, sometimes impassioned, style.

The First Encounter: Mutual Critique and Apprehension

The two composers first crossed paths in 1888 in Leipzig, during Tchaikovsky's concert tour through Germany. While they greeted each other courteously, it was clear from their conversations that they had differing opinions on each other’s music. Tchaikovsky reportedly found Brahms’s music “cold and academic,” while Brahms, though appreciating Tchaikovsky’s talent, was wary of the Russian’s tendency for overt emotion.

Tchaikovsky described Brahms in his diary as being “self-absorbed,” noting his straightforward, somewhat blunt manner. Brahms, for his part, seemed to struggle with Tchaikovsky’s more personal, heart-on-sleeve approach to music. Their interactions were tinged with a certain degree of intellectual skepticism, and yet, each seemed to acknowledge the other's contributions to music.

Brahms’s Reaction to Tchaikovsky’s Works

While Tchaikovsky’s criticisms of Brahms’s music often centered on his perception of its lack of warmth, Brahms’s reaction to Tchaikovsky’s compositions was more ambivalent. He acknowledged Tchaikovsky’s melodic genius, particularly admiring his ballet scores, yet found aspects of his music excessively lush and emotional. Brahms, who once declared himself "no lover of Tchaikovsky," was moved to tears upon hearing Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony (Pathétique), even admitting the power of its emotional depths.

Despite personal reservations, Brahms recommended Tchaikovsky’s music to various publishers, suggesting a degree of professional respect that transcended their stylistic differences. Brahms was often vocal about his opinions, but his tacit approval of Tchaikovsky’s work within the German music circles indicates that he saw genuine value in Tchaikovsky’s contributions.

Tchaikovsky’s Opinions on Brahms’s Music

Tchaikovsky’s opinions on Brahms evolved over time. Initially, he was frustrated by what he saw as Brahms’s restrictive classicism. He famously remarked that Brahms’s music felt “constructed rather than inspired.” However, after studying some of Brahms’s scores more closely, particularly the Symphony No. 1 and his chamber works, Tchaikovsky came to a reluctant appreciation for the German’s technique and craftsmanship.

The Russian composer admitted that Brahms had an “intellectual rigor” that he could not easily dismiss, and by the end of his life, Tchaikovsky acknowledged Brahms’s position within the musical world with more respect. His letters and diaries suggest that while he did not fully connect with Brahms’s artistic choices, he could appreciate the discipline and the intricacies within Brahms’s compositions.

Cultural Context: Nationalism and Musical Identity

Part of the tension between Brahms and Tchaikovsky can be attributed to the different cultural landscapes they represented. Tchaikovsky was often associated with the Russian nationalist movement in music, even though he did not fully identify with the radical nationalism espoused by “The Mighty Handful” (a group of nationalist Russian composers like Rimsky-Korsakov and Mussorgsky). Nevertheless, his compositions reflected a distinctly Russian identity, which was something that the German audiences were not entirely attuned to at the time.

Brahms, on the other hand, was steeped in the Germanic tradition and often found himself compared to Wagner—a figure who similarly polarized audiences. However, while Wagner and Tchaikovsky embraced a highly personal, dramatic approach, Brahms advocated for a more restrained and balanced ethos, drawing on folk influences within a highly structured framework. For Brahms, music was a language that should, ideally, transcend nationality, aiming instead for universality.

The Question of Emotional Expression: Different Paths to Musical Depth

A critical element in the relationship between Tchaikovsky and Brahms lies in their approach to emotional expression. Tchaikovsky’s music is frequently characterized by its raw emotional honesty. Pieces like the Symphony No. 6 (Pathétique) or Romeo and Juliet overflow with feeling, often reflecting the turmoil and conflict he experienced in his personal life.

Brahms, on the other hand, conveyed emotional depth through a more controlled musical language. His Symphony No. 4, for example, is rich in melancholy, yet the sorrow is articulated through carefully woven themes rather than overt outbursts. Brahms’s music does not lack passion; rather, it reveals itself subtly, demanding the listener’s careful attention and introspection.

While Tchaikovsky viewed Brahms’s emotional restraint as a deficiency, Brahms might have seen Tchaikovsky’s musical emotiveness as excessive. Yet, their diverging paths underscore the complexity of emotional communication in music—where Brahms’s restraint and Tchaikovsky’s unfiltered emotion represent two equally valid approaches to exploring human experience.

Legacy: Respect Beyond Differences

In retrospect, the relationship between Brahms and Tchaikovsky exemplifies how opposing musical philosophies can coexist within the same cultural landscape, each enriching the other. Although the two composers did not become friends, their professional respect laid a foundation for mutual acknowledgment. Tchaikovsky’s melodic and emotive works opened new avenues for expressing the Romantic spirit, while Brahms’s intellectual rigor and structural innovations reaffirmed the endurance of classical forms within Romanticism.

The legacy of Brahms and Tchaikovsky endures today, as both are celebrated for their unique contributions to the world of classical music. Their interactions reveal a nuanced picture of 19th-century Romanticism, a period where composers were not only challenging traditional forms but also grappling with the question of how best to capture the human experience through music.

Conclusion

While Tchaikovsky and Brahms may not have been the best of friends, they nonetheless shared a professional respect that transcended their stylistic differences. Their relationship reminds us that music, as an art form, thrives on diversity. The contrast between Tchaikovsky’s emotive openness and Brahms’s intellectual depth speaks to the multiplicity of human experience and the myriad ways composers have sought to express it. In this way, Tchaikovsky and Brahms’s “respect amidst differences” stands as a testament to the richness of the Romantic era, a time when music became a profound vehicle for both personal expression and universal connection.