The Maharaja of Music

Nikhil Sardana explores the strangely uncelebrated story of an Indian maharaja’s invaluable contribution to Western classical music.

The year was 1948. Europe was limping back to normalcy after seven terrible years of a world war. Richard Strauss had managed to escape his shattered homeland in the last year of the war and had settled in neutral Switzerland. It was here that the ailing 84-year-old composer wrote his farewell to the world through Four Last Songs, which included ‘Frühling’ (Spring), ‘September’, ‘Beim Schlafengehen’ (When Falling Asleep) and the haunting ‘Im Abendrot’ (At Sunset). He was never to hear them performed, but he expressed the desire to have them sung by the then-reigning Wagnerian soprano, Kirsten Flagstad, writing to her in 1949, “…I have the pleasure to provide to you my Four Last Songs with orchestra, which are currently in print in London; to give their premier performance in an orchestral concert with a first class conductor and orchestra…” He died soon after; his wish unfulfilled.

Invoking Strauss

Half a world away, similar turmoil, bloodshed and destruction had touched the lives of those living in the subcontinent of India. In 1947, a newly-formed nation had emerged into independence from British rule, and one of the first princely states to accede to the Dominion of India was Mysore. Its last ruler was the youthful Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar. That a 31-year-old Indian maharaja should be instrumental in carrying out the last wish of a legendary German composer is not as surprising as it may seem; Wadiyar was not only a musician of exceptional brilliance, but a patron of European classical music along the traditional lines of European royal patronage through the centuries.

Kirsten Flagstad, soprano, Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler | World Première, Royal Albert Hall, London, Recorded 22 May, 1950

The premiere of Four Last Songs was sponsored by Wadiyar, who offered some $5,000 at the time, which not only guaranteed the performance but paid for the cost of making a live recording of the work. This historic recording was added to his personal collection, which exceeded 20,000 records. The conductor at Royal Albert Hall, on May 22, 1950, was none other than Wilhelm Furtwängler who conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra, and the soprano was indeed, as Strauss had desired, Flagstad. And thereby hangs not just a tale, but a veritable saga.

The pianist

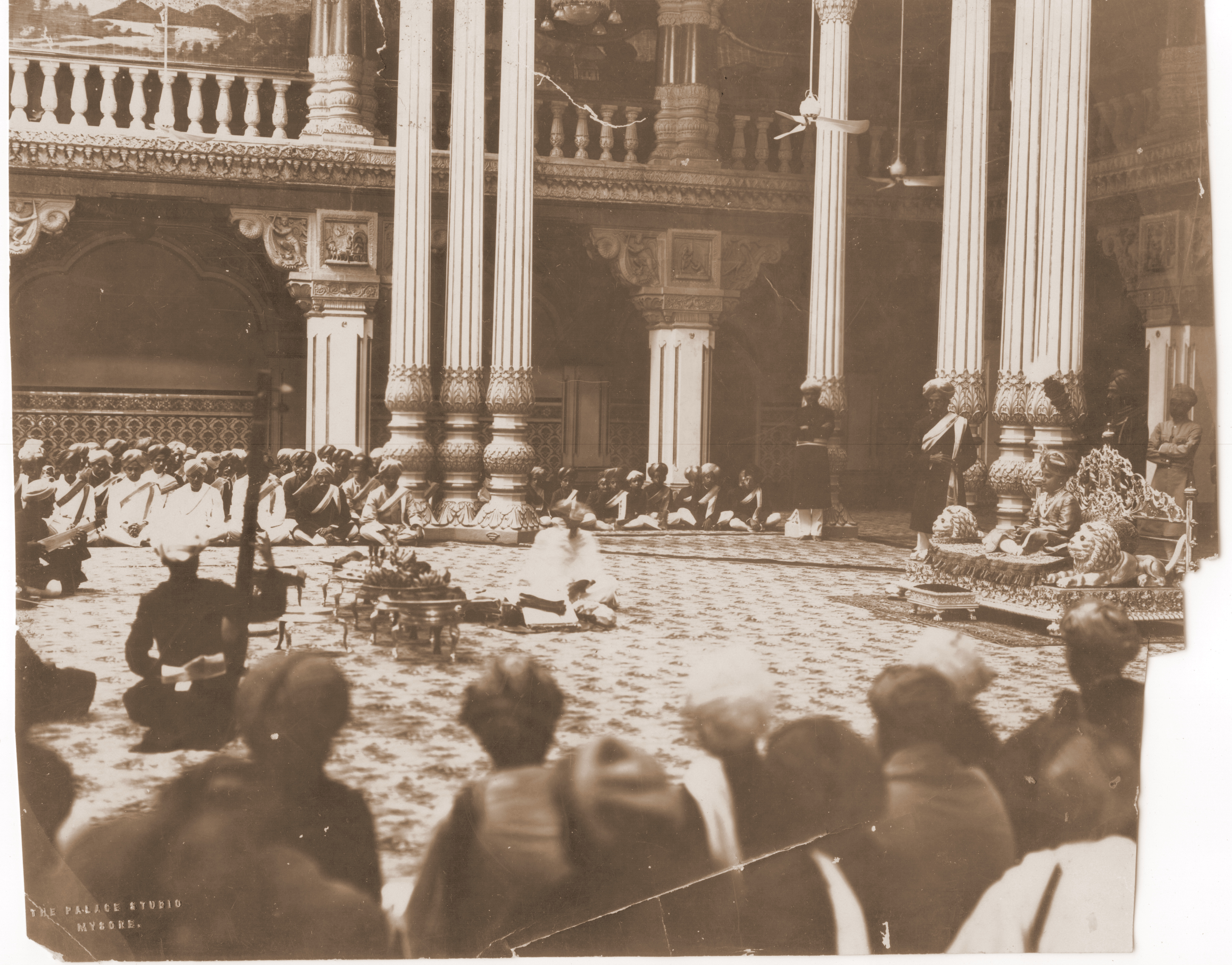

Wadiyar had ascended the throne in 1940, at the age of 21 after the death of his natural father Kantheerava Narasimharaja Wadiyar and his uncle Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV, Maharaja of Mysore. His sister Vijaya Devi has reminisced, “Had my brother not been heir apparent, I expect he would have gone seriously into studying the piano.” The cultural atmosphere of the palace where the young prince and his sisters grew up, had, she has said, a “profound influence on us…I do not remember any function, formal or informal, of which music did not form an integral part.” Though the young royals grew up with Carnatic music and dance, their earliest music studies commenced with piano lessons for the young prince with the “very good” but strict teacher, Sister Ignatius from the Good Shepherd Convent in Mysore. The young Wadiyar’s talent was evident at a very early stage. His sister recalled that at a piano examination, after he had finished playing, the examiner Dr. Adolf Mann went to the piano and played Handel’s rousing song ‘See, the Conqu’ring Hero Comes!’ as an affectionate acknowledgment of the child’s incredible performance. The young boy, according to his sister, “was thrilled to bits.” Western classical music thus became an early passion with him and though unable to attend live concerts, he acquired a huge record collection which helped him to develop his powers of appreciation and discrimination to an advanced degree.

Vijaya Devi herself went on to become a proficient pianist, gaining, like her brother, qualifications from Trinity College London and later continuing her piano studies under the eminent musician and professor Edward Steuermann of the Juilliard School of Music in New York. In 1974, at the suggestion of her brother, she founded the International Music & Arts Society (IMAS) in Bengaluru. This institution continues to function under the active engagement and guidance of her daughter, Urmila Devi.

Early years and influences

Both children grew up under the supportive gaze of a father who was a jazz aficionado. He would introduce the young Wadiyar and his sister to guests as “my two highbrow children”. The young maharaja acquired a Licentiateship in Piano Performance from the Guildhall School of Music & Drama and was granted an honorary Fellowship of Trinity College London in 1945. Shortly before his coronation, he visited Sergei Rachmaninoff in Switzerland looking to being accepted by the legendary pianist and composer as a student. It was perhaps during this European tour that he had occasion to listen to works by the Russian composer Nikolai Medtner (1880-1951).

Though the two never met, Wadiyar financed a series of recordings for HMV, a debt that was repaid by Medtner dedicating his Third Piano Concerto to him. Writing in Gramophone (1948), critic Fred Smith described the recording as “one of the greatest romances in the history of the gramophone”. For the reclusive composer living a quiet life in London, it was, commented Smith, “wonderful that destiny should have brought Medtner’s genius within the spheres of vision and great musical appreciation of the HH The Maharaja of Mysore…I shall not forget the look of wonder in Medtner’s countenance as Captain Binstead, the Maharaja of Mysore’s Commissioner, in my presence, put the proposal to him. What a service has been rendered to music…” The recordings were made with an expert team, and the albums went a long way in, as Smith poetically put it, giving Medtner due recognition “in the autumn of his life”.

Wadiyar was so appreciative of his music that, in 1949, he formed ‘The Medtner Society’ and continued being instrumental in spreading awareness about this little-known composer’s work throughout his life.

Patron of the arts

It is an instance of Wadiyar’s very marked preferences in music, displaying a highly individual aesthetic. Medtner was never as well-known as his contemporaries such as Rachmaninoff and Scriabin. One reason could be Medtner’s austere artistic integrity, the fact that his piano writing was simply not accessible to amateurs, and the lack of melodic appeal in his music. His music was complicated, texturally dense and often slow to the point of being meditative. It is interesting to speculate that one reason why such music found an instant response in Wadiyar was his exposure to an understanding of the complexities of music traditions other than European, namely Carnatic music. Through Medtner, the Maharaja’s wider contribution to Western classical music came to pass because it led to his meeting and subsequent involvement with Walter Legge – classical music producer for EMI at the time.

Legge was a veteran in the recording industry, a man of many gifts; music critic and assistant to English conductor Thomas Beecham. After the war, he revitalised EMI with subscription recordings featuring many of the great conductors and performers of the time. The Philharmonia Orchestra, which he established primarily as a recording orchestra, featured Beecham as the first conductor (he wielded the baton for a fee of one cigar). Legge was in search of sufficient royalties to buttress the orchestra’s finances. His invitation to Mysore to discuss possible recordings of Medtner’s works was, in his own words (in a letter to pianist Egon Petri),

“the sort of miracle that happens only once in a lifetime…an Indian Prince has interested himself in neglected European music and commissioned us to record certain works.”

Again, from his accounts, his first visit to the palace was a “fantastic experience”. Legge was deeply impressed by this young man who had a mammoth record collection, sound systems, many concert grand pianos, and above all, a deep knowledge of music and tremendous generosity in promoting its growth. It was a highly successful visit because not only did the Maharaja agree to pay for some of Medtner’s music but also offered a yearly grant of £10,000 for three years which would enable Legge to put the Philharmonia Orchestra and the Concert Society (Wadiyar was the first President of the latter) on a sound financial footing.

The scholar’s edict

With this sum Legge was able to take on the dynamic German conductor Herbert von Karajan. The conductor, who had never met Wadiyar, said of him,

“I was fascinated by this man because he wanted, above all things, for us to record the Bartók Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta. There was no recording at that time, and it was a very difficult piece for the orchestra to bring off but I was determined to do it. In a way, the very roots of music are touched on in this work.”

It was this discernment of “the very roots of music” that set Wadiyar apart from other wealthy and knowledgeable patrons of music. This is evident from the kind of repertoire he wished to sponsor – Balakirev’s First Symphony, Scriabin’s Piano Concerto, among others. These are works that have gone on to become some of the greatest recordings of the time and in themselves, are recognised masterpieces of Western art music.

He was equally specific about performers he was interested in. For example, he proposed a fee of £600 for the great pianist Egon Petri to travel to London and record Busoni’s Indian Fantasy. In writing to Petri, Legge observed wryly,

“His Highness, being both a prince and young man, is impatient for the realisation of his dreams for a first-class recording on this work.”

Petri regretfully declined, while thanking the Maharaja “most warmly for his generous offer” citing health reasons for not travelling. Legge replied,

“I wish I could say ‘yes’ to recording in Hollywood, but my Maharaja insists on London recording – and mine not to reason why!”

Instead of Petri, Legge had a young Romanian perform. He would later come to be known as one of the most gifted pianists of all time: Dinu Lipatti (who died tragically young). Wadiyar was highly appreciative of Lipatti’s performances saying, when he heard of his death, “Lipatti was a real genius. But it is a cruel world we live in.” Lipatti died nine days before he was to have performed a concert at the Royal Albert Hall under the baton of Furtwängler for around 4,000 people. After this concert, the conductor told the Press Trust of India that by sponsoring these concerts in London, the Maharaja of Mysore was being a great patron of the best in Western music. The post-concert reception was hosted by the Marchioness of Willingdon and the Indian High Commissioner, V.K. Krishna Menon.

Generous and astute

Wadiyar was unequivocal in his opinions of performers and performances. While having a high regard for the pianist Artur Schnabel, he dismissed him as a composer, saying his music was lacking in originality and inspiration. Modestly calling himself a layman, he said that only repeated hearings could convince “us personally. Twenty-five hearings have not convinced me.” In his suggestions for recording Schumann’s works for piano, he recommended specific pianists; Soloman, Lipatti, Gieseking, Moiseiwitsch. In the same letter to Legge, he revealed his eclectic and highly developed musical palate in suggesting the Mass by Leoš Janáček and the piano concerto by Albert Rousell, revealing that he was “very anxious” to have these far from popular works available in recording.

Though often making light of his unshakeable musical judgement (“My choices keep varying daily according to my moods”), he nevertheless was firm in his support of Karajan’s and Furtwängler’s Beethoven interpretations, and equally forthright about Toscanini’s, calling them “highly strung, vicious… abominable”. Toscanini, at the time, was already a legend, but Wadiyar clearly had very definite standards by which he critiqued music. He was equally dismissive of some other legends, damning Rubinstein’s performance of his Beethoven sonata Op. 31 No. 3, and using the word “abominable” for Wilhelm Backhaus’s interpretations of some other Beethoven sonatas. His strong opinions clearly revealed an encyclopedic knowledge of the compositions.

Paying it forward

The Maharaja of Mysore’s Musical Foundation was the umbrella under which the recordings of Medtner’s works were made possible. His intention was to use the foundation to examine similarly neglected composers and/or works which had not reached the public because of lack of recordings. Clearly he realised how much his own musical education and knowledge was due to his necessary reliance on recordings. A true visionary by nature, he wanted to share this path of accessibility to make music available to the public. He finalised and gave his consent to a five-year recording plan, for which, a list was made in consultation with eminent musicians worldwide. Gramophone magazine reported in 1950, that “it is his Highness’s wish to be guided in the final choice of works by the desires of the music-loving and record-buying public.” The highly imaginative way this was achieved was by floating two competitions to select works from a given list, according to personal preference and what was perceived as being of general interest.

After this voting exercise Gramophone wrote:

“Many more correspondents have written expressing their admiration for the vision, constructive enterprise and generosity of the young Indian Prince who conceived this plan, and who is making it possible for music lovers throughout the world to learn, enjoy and study works which, but for his knowledge and love of music, would never have been recorded.”

Wadiyar’s grant was sufficient to tide the Philharmonia Orchestra over a difficult financial period until its own record sales were sufficient to keep it going. The sales were, in fact, crucial because the promised yearly grant of £10,000 was reduced to £5,000 after the first year and stopped completely after two years. This was, of course, inevitable, given that Mysore was no longer an independent state, either politically or financially, in the new Republic of India.

Aftermath

The new Republic had need of men like him. Polymath, visionary, philanthropist, an experienced and dedicated administrator, Wadiyar was appointed Governor of Mysore and later, of Madras. Before assuming his new office he said, “…the rule of the Maharajas has indeed fulfilled its purpose, the purpose of making the people fit to rule themselves.”

The philosopher-prince had moved with grace and wisdom into his new role, saying, “let us aspire to achieve the Ram Rajya of Gandhiji’s dream.” He died in 1974 at the age of 55 having given, in the short span of years allotted to him, much of great value in the fields of not only Western and Carnatic music, but also of education, governance, healthcare and the well- being of his people, whom he had guided so wisely and so well.

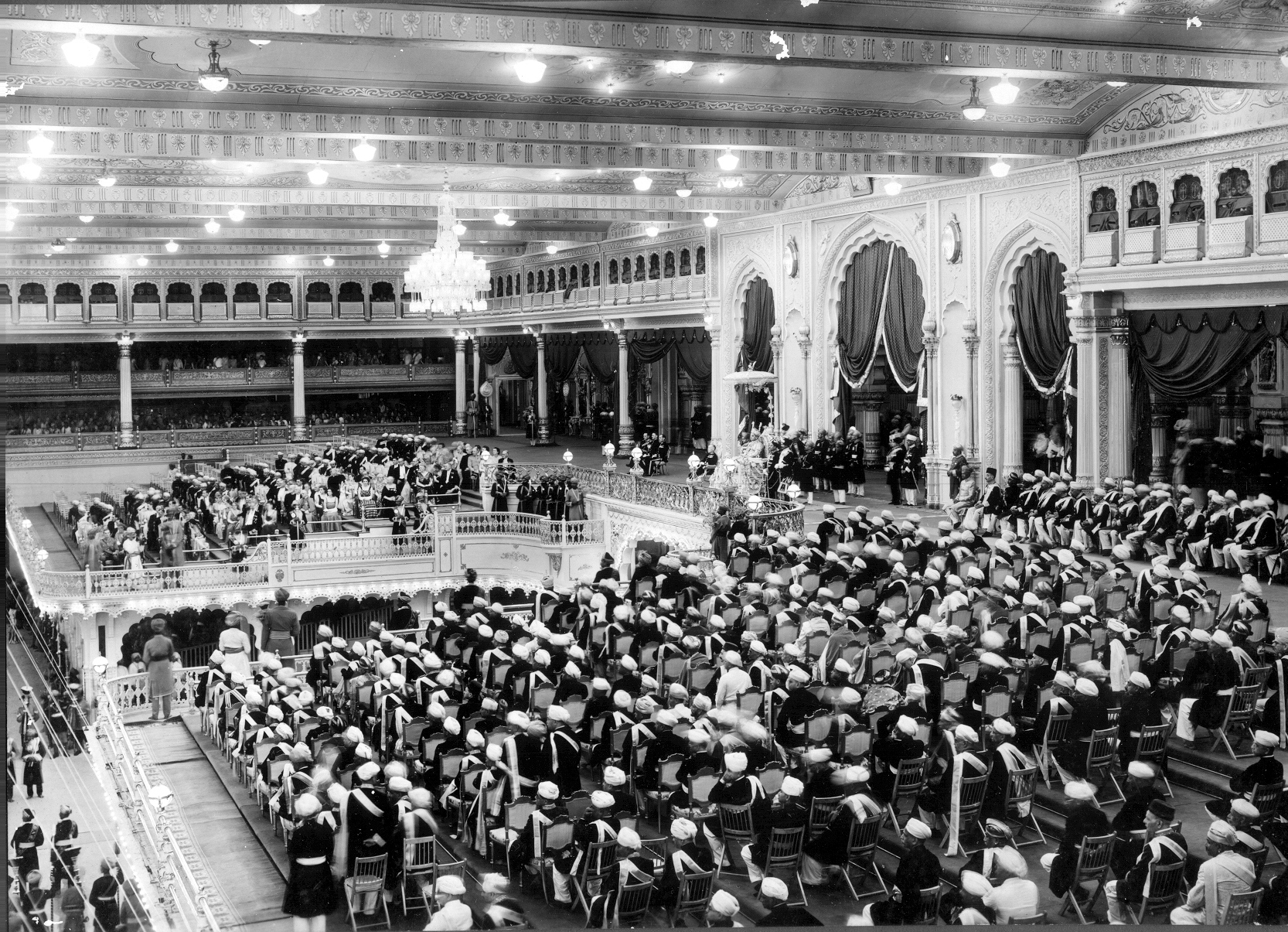

The grandeur of the princely state of Mysore is well-known. The majestic Dasara procession and the magnificent palace have been captured in a thousand images. But what this one man achieved, he did out of the spiritual richness of his heart and mind, and that is a legacy that will endure.

All Images have been sourced from the private collection of the Wadiyar family.

The SOI Chamber Orchestra will perform on 18th July at the Mysore Palace and on 20th July at the Bangalore Palace.

This piece was originally published in two parts by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the June and July 2019 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.