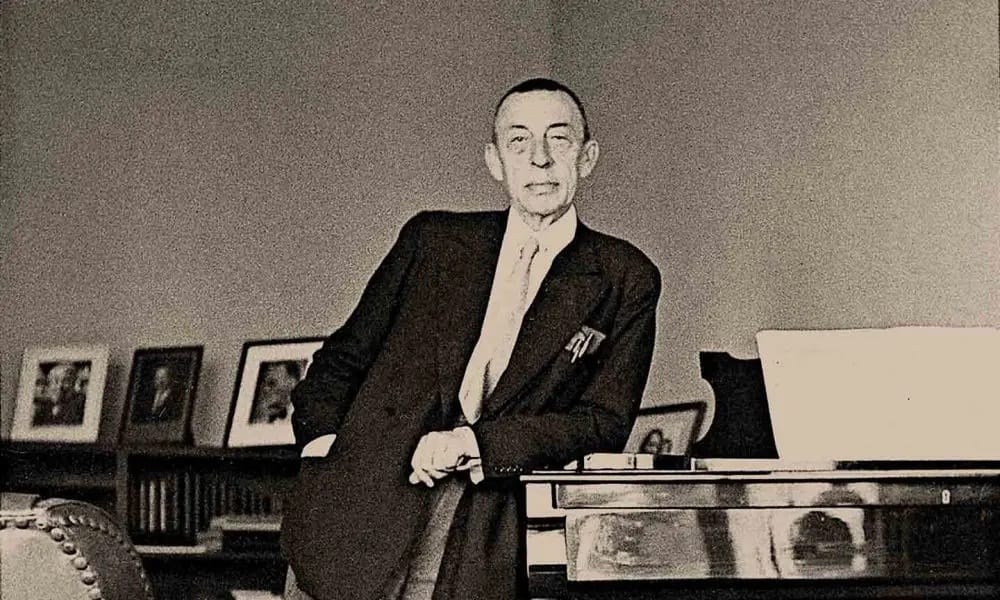

Sergei Vasilyevich Rachmaninov (1873 – 1943): All by Himself

Canadian singer Celine Dion was in the news on account of her recent diagnosis with the crippling rare neurologic condition stiff-person disorder, causing her to cancel future concert tours.

I was listening to one of her signature songs, ‘All by Myself’, which was actually written nearly fifty years ago, in 1975, by American singer-songwriter Eric Carmen, former lead vocalist of the Raspberries.

But if you look at the official song credit, Eric Carmen isn’t “all by himself”; he shares the space with a certain Sergei Rachmaninov! Which is quite a feat, given that Rachmaninov died in 1943.

But his music lived on, and that is what “inspired” Carmen. To be precise, it was the brooding theme from the second movement (Adagio sostenuto) of Rachmaninov’s circa 1900–1901 Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, Opus 18.

Rachmaninov’s music was in the public domain in the United States at that time, so Carmen thought no copyright existed on it, but it was still protected outside the U.S. after the release of the album. Carmen realised this when contacted by the Rachmaninov estate. An agreement was reached in which the estate would receive 12 percent of the royalties from “All by Myself” as well as from “Never Gonna Fall in Love Again”, which was based on the third movement from Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 2.

This year happens to be Rachmaninov’s 150th birth centenary, a milestone being celebrated worldwide.

He was born into an aristocratic family with a strong musical background. His paternal grandfather Arkady Alexandrovich, was a musician who had taken lessons from Irish composer John Field. Young Sergei’s musical gift was detected early by his mother; he was able to reproduce passages flawlessly from memory. Piano and music lessons began at age four with a resident tutor, Anna Ornatskaya, a teacher and recent graduate of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. Rachmaninov’s famous romance for voice and piano “Spring Waters” from 12 Romances, Op. 14 is dedicated to her.

At age ten, he went to study music at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. Later that same year (1883) his sister Sofia died of diphtheria. In 1885, the death of another sister Yelena to pernicious anaemia was another blow. Yelena had been an important musical influence and had introduced him to the works of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

Rachmaninov transferred that year to the Moscow Conservatory. For his final theory and composition exam he in just seventeen days composed ‘Aleko’ (1892), a one-act opera based on the narrative poem The Gypsies by Alexander Pushkin. It earned him the highest mark at the Conservatory and a Great Gold Medal, a distinction only previously awarded to great Russian composers Sergei Taneyev (now his teacher at the Conservatory) and Arseny Koreshchenko. The Conservatory issued Rachmaninov a diploma which allowed him to officially style himself as a “Free Artist”. Tchaikovsky attended the premiere of ‘Aleko’ at the Bolshoi theatre and praised Rachmaninov for the work, something that must have done wonders to the self-confidence of a nineteen-year-old fledgling composer.

The next year Rachmaninov composed a tone poem ‘The Rock’ (which he dedicated to another great Russian composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov) which Tchaikovsky agreed to conduct for an upcoming European tour.

One can only imagine what a blow the sudden death of Tchaikovsky from cholera (conspiracy theories of ‘enforced suicide’ are now discredited) later in 1893 would therefore have been to Rachmaninov. His Trio élégiaque No. 2 in D minor, Op. 9, inscribed with the dedication ‘In Memory of a Great Artist,’ was composed as a grieving tribute within a few weeks. Significantly, its second movement consists of variations of the main theme of ‘The Rock’.

The shocking news however sapped him of further inspiration to compose. He also lost interest in showcasing ‘Aleko’.

He prematurely quit a concert tour and forfeited the performance fees from cancelled concerts. Rachmaninov hated giving piano lessons but was compelled to in order to earn money, on one occasion even having to pawn a treasured gold watch.

Nevertheless, he laboured over his First Symphony (based on chants he had heard in Russian Orthodox church services) for most of 1895. Unfortunately, the premiere of its performance at St. Petersburg in 1897 was a disaster. It was conducted by Russian composer Alexander Glazunov who didn’t understand the work, squandered precious rehearsal time on other works in the program, and is even alleged to have been inebriated at the concert. At any rate, the work was brutally panned by critic and nationalist composer César Cui, who wrote:

“If there were a conservatory in Hell, and if one of its talented students were to compose a programme symphony based on the story of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, and if he were to compose a symphony like Mr. Rachmaninov’s, then he would have fulfilled his task brilliantly and would delight the inhabitants of Hell. To us this music leaves an evil impression with its broken rhythms, obscurity and vagueness of form, meaningless repetition of the same short tricks, the nasal sound of the orchestra, the strained crash of the brass, and above all its sickly perverse harmonization and quasi-melodic outlines, the complete absence of simplicity and naturalness, the complete absence of themes.”

The symphony would not be performed again for the rest of Rachmaninov’s life.

He told his biographer much later: “I returned to Moscow a changed man. My confidence in myself had received a sudden blow. Agonizing hours spent in doubt and hard thinking had brought me to the conclusion that I ought to give up composing.”

Rachmaninov fell into a deep depression that would last several years, during which he suffered what we would today call “writer’s block”, and composed almost nothing. In his words, during those years he was “like a man who had suffered a stroke and for a long time had lost the use of his head and hands” Piano lessons and conducting assignments kept him going.

A meeting arranged with his hero Leo Tolstoy was anticlimactic: “Does anyone want this type of music?” Tolstoy said witheringly of his work.

Thankfully, daily hypnotherapy sessions with family friend, amateur musician, and neurologist Nikolai Dahl in 1900 reversed the depressive tide. In gratitude, Rachmaninov dedicated his first fully completed work, the Second Piano concerto to Dahl.

Music from the Second Piano concerto was used to great effect in Sir David Lean’s classic film ‘Brief Encounter’ (1945), just two years after Rachmaninov’s death.

I think of this moment in music history where a medical intervention made such a pivotal difference. Even Rachmaninov’s lifespan might have been shorter had it not been for Dahl’s timely treatment. Imagine how much the poorer the world would be had the fog of depression and writer’s block never been dispelled. Rachmaninov continued to compose until almost the last years of his life.

Dr. Dahl emigrated to Beirut in 1925 and played viola in the orchestra of the American University there. On one occasion, when Rachmaninov’s Second Piano concerto was performed, the audience was informed that its dedicatee Dr. Dahl was in the orchestra’s viola section. He was asked to rise and take a much-deserved bow.

This article first appeared in The Navhind Times, Goa, India.