Schubert’s Piano Sonata No.21 in B-flat Major, Mitsuko Uchida

“The opening movement of the Sonata [No. 21] in B-flat Major goes beyond analysis,” writes the pianist Stephen Hough. “It is one of those occasions when the pen has to be set down on the desk, the body rested against the back of a chair, and a listener’s whole being surrendered to another sphere.”

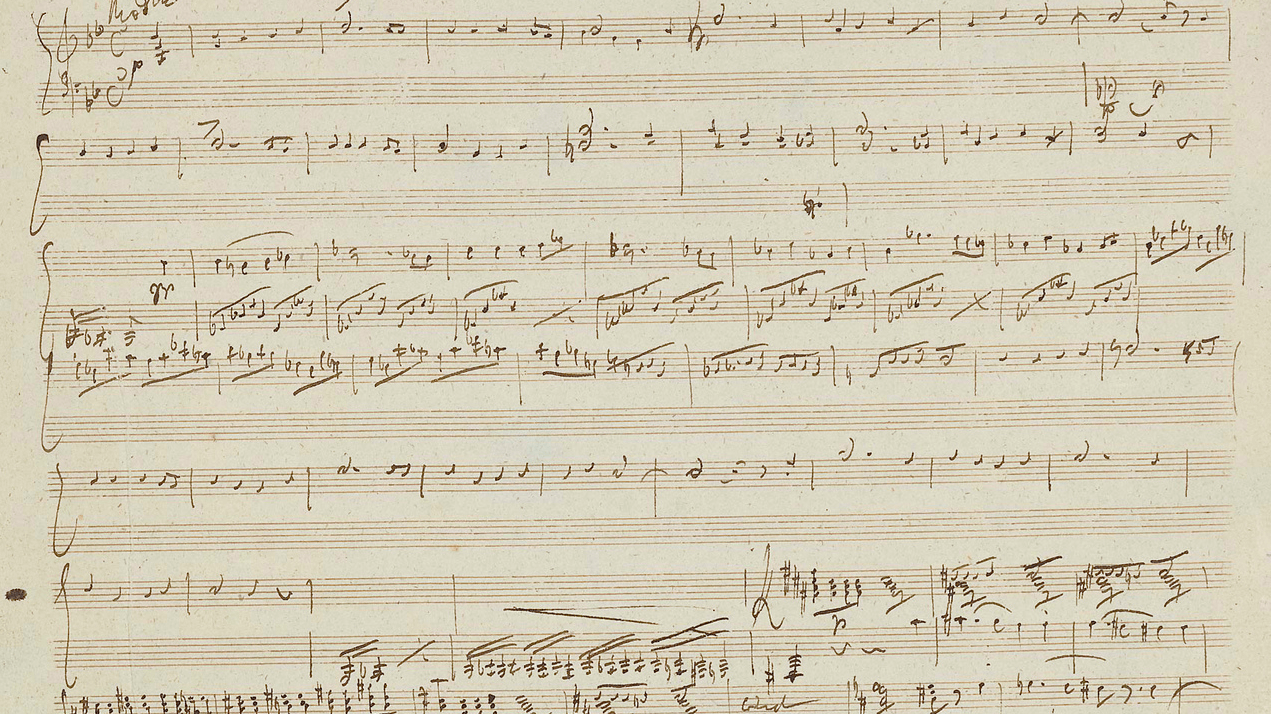

This was Franz Schubert’s last instrumental work. Completed in the autumn of 1828 during the final months of the composer’s life, it concludes a set of three piano sonatas which the biographer George R. Marek described as “works in which meditation, charm, wistfulness, sadness and joy are housed in noble structures.” Alfred Brendel said that these pieces “lead us into romantic regions of wonderment, terror and awe.” They inhabit the same place of mystery and divine revelation we encounter in Beethoven’s late string quartets. Yet, the journey we take is distinctly introspective and solitary. This music unfolds with an effortless stream of melody which is shaped by sudden, transcendent modulations. Robert Schumann described the “heavenly length” of Schubert’s “Great” Ninth Symphony. In Piano Sonata No. 21, there is a similar sense of timelessness, quiet majesty, and cosmic expanse.

In the opening bars of the first movement, we enter a world of celestial calm, reverence, and lament. Suddenly, the serene melody is interrupted by the ghostly rumble of a low G-flat trill which breaks off into silence. This mysterious intrusion gives us a glimpse of the terrifying, yet fleeting, nocturnal shadows of Schubert’s Erlkönig. The pianist András Schiff has gone so far as to call it “the most extraordinary trill in the history of music.” It returns as a haunting presence throughout the first movement and at times shifts the harmonic path towards G-flat major and its enharmonic equivalent of F-sharp minor. With a three-key exposition and an expansive development section, the first movement opens the door to a vast, yet intimate, drama.

The Andante sostenuto moves to the distant key of C-sharp minor. The musicologist Alfred Einstein called this movement, “the climax and apotheosis of Schubert’s instrumental lyricism and his simplicity of form.” The music is dreamy and hypnotic, with a somber underlying rocking rhythm which turns into a tender lullaby. Sudden shifts between major and minor and transcendent modulations open up otherworldly vistas. It is simultaneously a serene prayer of gratitude and a wistful “farewell.”

The profound dramatic weight of the first two movements is swept away by the brief, sunny Scherzo. Marked delicatezza, it is a light, playful dance which takes delight in veering in unpredictable harmonic directions. Perhaps there is still a tinge of sadness in this bright, frolicking music.

A single, attention-grabbing note launches the finale into motion. A combination of sonata and rondo form, this movement takes us on a thrilling harmonic and thematic journey. Again, the music alternates unpredictably between minor and major, sadness and jubilation. In the final moments, our memory of the haunting trill of the first movement recedes. The music takes on a sparkling innocence, and the coda surges forward with a joyful lightness of spirit.

I. Molto moderato:

II. Andante sostenuto:

III. Scherzo (Allegro vivace con delicatezza):

IV. Allegro ma non troppo:

This article first appeared on The Listeners’ Club.