Three Spectacular Evenings at the Philharmonie de Paris

The weekend before Passion Sunday the merrymaking in Paris’ huge Philharmonie Grande Salle began. On Sunday, 3rd April, the main attraction was a liederabend by two vocal stars: Diana Damrau and Jonas Kaufmann. The expectation in the hall was heavily pregnant with anticipation. It is rare that two huge vocal talents unite for a long evening programming, the best choices from the romantic lieder repertoire of Schumann and Brahms.

Kaufmann is well known on the operatic stage but does he really make a good lieder recitalist? He has proved time and again that he is successful in French, Italian and German opera alike. Some years ago, he made a not entirely successful recording of Schubert’s Die Winterreise. In 2018 following successful concerts where again he paired up with Diana Damrau to perform, they recorded Wolf’s Italienisches Liederbuch. Following on from the immense success that that met with is the current performance under review.

Damrau is fully his equal on the recital platform as well as the opera house. She is equally at home in French and Italian opera but as yet eschews the heavier Germanic fare. They made a special partnership passionate and coquettish in turns.

The choice of programming included the familiar with the almost unknown. The duets were genuinely rare and very beautiful indeed. The two singers were partnered by the indefatigable Helmut Deutsch who probably knows his lieder better than anyone else. He must have had a major role in selecting the repertoire and the order of the programme. The opening group of seven Schumann songs began with the famous Widmung from the Myrten cycle. Usually sung by a woman, this however was sung by Kaufmann to open the recital. The two singers remained on stage right through in spite of being silent often for several songs at a stretch. The next seven songs were by Brahms and the first half ended with five more Schumann lieder.

The second half began with Brahms’ gorgeous setting of Vergebliches Ständchen sung as a duet. After five more settings by Brahms, there were six Schumann songs before the final offering of eight songs again by Brahms.

After the first few minutes when his voice took some time warming up, Kaufmann came into his stride. His tone was golden and deep and often beautiful, even at extremes of pitch and dynamics. He had a warm and caressing mezza di voce and his breathing and control were exemplary. Singing in his own language his diction was perfect. Similarly Damrau was poised and effortless matching her partner with every subtlety and nuance. The pianist Helmut Deutsch is a singer’s dream. By turns, leading and following, he was indispensable to the success of the evening.

The next day at the Philharmonie was Monday, 4th April, with a performance of Bach’s St Matthew Passion. Although the date of its premiere is not altogether determined, it was probably created and first performed in the year 1727. The occasion was Good Friday and the devoutly religious composer had arrived in Leipzig a few years earlier to take up the post of Cantor of Thomaskirche. Bach’s earlier and less colossal Passion, the one according to St John, was written in 1724. The larger of the two surviving passions, the Matthew Passion was written in 1727 for soloists, double choir and double orchestra. This, along with the Mass in B minor, is arguably Bach’s greatest religious choral masterpiece. It is as well the closest that Bach got to composing an opera. Bach had composed 3 more such Passions or dramatic oratorios which have not survived.

The Matthew Passion is a dramatic retelling of Gospels according to St Matthew chapters 26th and 27th of the Lutheran Bible using paraphrasing as well as the original texts fashioned into a libretto by Picander. In Leipzig at that time it was disallowed to publicly perform a paraphrase of the original Gospel texts on Good Friday. So for his earlier passion, the one according to St John, Bach chose to set the original Gospel texts in 1724. In 1725 a local poet paraphrased the two chapters of the Gospel in free verse with interspersed chorales and arias. His name was CF Henrici (pen name Picander) and Bach was persuaded to break from tradition in this glorious representation of the poet’s thoughts on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday.

Since 1975, it has usually been assumed that Bach's St Matthew Passion was first performed on Good Friday (11 April, 1727), although its first performance may have been as late as Good Friday in 1729. The performance took place in the St. Thomas Church (Thomaskirche) in Leipzig. Bach had been Thomaskantor (i.e., Cantor, and responsible for the music in the church) since 1723. In this version, the Passion was written for two choruses and orchestras. Choir I consists of a soprano in ripieno voice, a soprano solo, an alto solo, a tenor solo, SATB chorus, two traversos, two oboes, two oboes d'amore, two oboes da caccia, lute, strings (two violin sections, violas and cellos), and continuo (at least organ). Choir II consists of SATB voices, violin I, violin II, viola, viola da gamba, cello, two traversos, two oboes (d'amore) and possibly continuo.

At the time only men sang in church: high pitch vocal parts were usually performed by treble choristers. The total number of voices were a choir of twelve singers, plus eight other singers. At least some of the Passion presentations in St. Thomas were with fewer than twenty singers, even for the large scale works, like the St Matthew Passion, that were written for double choir.

In Bach's time, St. Thomas Church had two organ lofts: the large organ loft that was used throughout the year for musicians performing in Sunday services, vespers, etc., and the small organ loft, situated at the opposite side of the former, that was used additionally in the grand services for Christmas and Easter. The St Matthew Passion was composed as to perform a single work from both organ lofts at the same time: chorus and orchestra would occupy the large organ loft, and chorus and orchestra II performed from the small organ loft. The size of the organ lofts limited the number of performers for each choir. Large choruses, in addition to the instrumentists indicated for Choir I and II, would have been impossible, so also here there is an indication that each part (including those of strings and singers) would have a limited number of performers, where, for the choruses, the numbers would be a maximum of what could be fitted in the organ lofts.

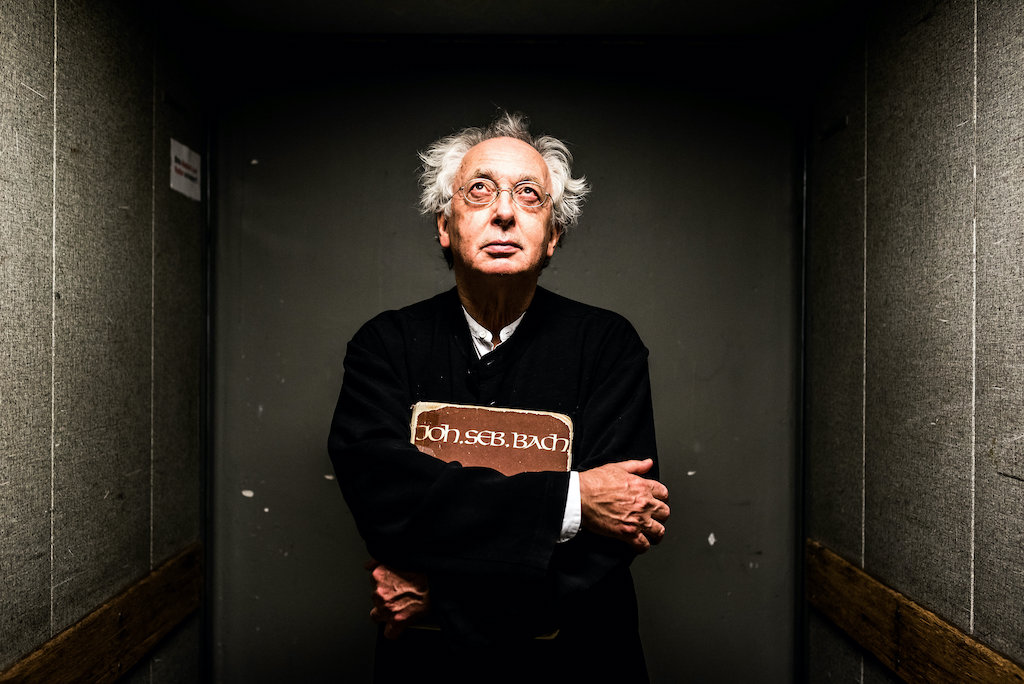

This performance was miraculously brought to life with the effervescent and incandescent conducting of Philippe Herreweghe. The Belgian conductor, born in Ghent, established the Collegium Vocale Gent (CVG) way back in 1970. It is scarcely believable that it has been going for over 50 years and still sounds freshly minted. The sound of original instruments and period-informed vocal and instrumental techniques are now commonplace both in recordings and live performances. The clarity of diction with smaller forces gave an edge to the recitatives and arias yet amassing adequate swathes of sound in the chorales with antiphony between the 2 choirs and resonant orchestral playing. The 2 orchestras faced each other on either side of the conductor as were the 2 choirs. The soloists for the arias emerged from the choir on the right. All the 10 vocal soloists excelled.

The third night (Tuesday, 5th April) of this trilogy of concerts at the Philharmonie was a solo piano recital by the young Russian pianist, Daniil Trifonov. He is only 31 years old and already described as one of the days leading virtuosos and probably one of the most outstanding pianists of our times. Since his win in the 2011 Tchaikovsky Competition at the age of 20, he has gone on to play in the major concert halls of the world and with all top orchestras including the Berlin Philharmonic. In the same year, he won first prize and Grand Prix at the Tchaikovsky in Moscow as well as the Rubinstein International Competition in Israel. A year earlier in 2010, he placed among the winners of the Chopin Competition. At the age of 23, he was signed by DG recording the Art of Fugue by Bach as his third release in October 2021. This is an audacious choice by someone so young. Although pleading an arm injury on that day, he completed a truncated programme with his own completion of the unfinished masterpiece with formidable skill. Born in Nizhny Novgorod, Trifonov began studying piano at the age of five and performed in his first solo recital at the age of seven. In 2000, he began studying at the Gnessin School of Music in Moscow. From 2009 to 2015 he studied with Sergei Babayan at the Cleveland Institute of Music.

The Art of Fugue is an incomplete musical work of unspecified instrumentation by Johann Sebastian Bach. Written in the last decade of his life, it is the culmination of Bach's experimentation with mono-thematic instrumental works and along with its religious valedictory counterpart, the Mass in B minor represents the pinnacle of his music. This work consists of 14 fugues and four canons in D minor, each using some variation of a single principal subject, and generally ordered to increase in complexity. The idea of the work is an exploration of the contrapuntal possibilities inherent in a single musical subject. The word "contrapunctus" is often used for each fugue. Although the score is incomplete, there is no consensus on the nature of the instrumental forces required. It can be performed by solo organ, harpsichord or piano, as well as by a string quartet or orchestra.

It is not an easy work to perform nor is it easy to listen to. Although adept voicing of fugal parts is necessary, there is much rhythmic flexibility in its original note values. There is little room for agogic devices, apart from the occasional rallentando, which is virtually at the same tempo throughout. The interval came between Contrapunctus XI and XII with the pianist continuing the second half with an uncanny exactness of tempo. The music demands the utmost virtuosity and sensitivity from the interpreter. Anyone attempting to perform it requires a special musical insight and unlimited virtuosic ability. This Trifonov has in spades. I can only imagine a handful of contemporary musicians and certainly him alone who can fit the bill. Extremes of dynamic contrast were possibly excessive and drew attention to himself rather self consciously. Sometimes, especially early on, I thought he tended to bang a bit and over emphasise certain voices. At the same time, he could be extremely subtle and soft-grained. Although very much a pianist’s pianist, he could over intellectualise the interpretation. Unfortunately, he did not perform the arrangement of Bach’s Chaconne from the D minor violin partita in Brahms’ arrangement for left-hand alone. In his performance that evening, apart from the truncated programme, there was no evidence that physically he was not up to his best. The only visible sign was probably his right elbow that was painful with a slight stiffness and a lack of swing when he walked off stage. Following a built-in encore (the Myra Hess arrangement of Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring) was a short piece by presumably one of Bach’s four sons. All in all an electrifying conclusion!