THE LAST MAN WHO KNEW EVERYTHING?

Video Credit: Petrovsky & Ramone – Dutch National Opera

A review of Dutch National Opera’s innovative new offering

I am running late. My plan to arrive at Weesperplien Station before 7pm to get to the theatre in time has gone awry. I prepare myself for the possibility of not being able to purchase a programme, leave alone read it. Adding to the rush, the unhelpfully long exit delays me further and upon surfacing to street level I stop a local to ask for directions. I am pointed toward the Amstel river and make haste in the approximate direction, somewhat dubious about the stranger’s instruction. A lesson learnt is never, never doubt a local.

The Carré Theatre greets me from the riverside, glistening in the water as I approach. It is a bustling summer evening and Amsterdam’s Holland Festival is in full swing. I arrive, breathless, with just enough time to purchase a programme for the premiere night of Louis Andriessen’s Theatre of the World. A steward shows me to my seat and I wait eagerly.

Born in 1939, the composer is regarded as a leading figure in contemporary music and arguably the father of modern music in the Netherlands. His formal compositional education commenced at the Royal Conservatory of the Hague under Kees Van Baaren and was soon followed by two further years of study with the veritable Luciano Berio in Milan and Berlin. Andriessen’s reputation has, unsurprisingly, grown exponentially over his career and his eighth operatic endeavour is widely anticipated.

Opera is a medium that Andriessen, along with many other contemporary composers, has favoured throughout his career due to its seemingly inexhaustible opportunities through which to express his artistic ideas and humanist concerns. Tonight I hope to witness an exhilarating collaboration of music, animation, stage design and narrative, creating a true theatrical experience in many senses. The performance lies in the hands of the usual performers of Andriessen’s operatic premieres, the Dutch National Opera.

With Pierre Audi at its helm as resident artistic director, the opera company, celebrating its 50th year “creates and performs dramatic musical art, focussing on quality, diversity and innovation”. Audi will be stepping down after two more seasons to commence his appointment as general director at the prestigious Festival d’Aix-en-Provence in 2018. The artistic vision that Audi has brought to the Dutch National Opera over the last 30 years demonstrates his genius in both reimagining operatic standards and producing impressive displays of postmodern contemporary opera. His legacy has been best described by his colleague Els van der Plas, the general director of Dutch National Opera and Ballet. “As a company, organization and audience we have been fortunate to reap the artistic fruits of his leadership. The robust national and international position of Dutch National Opera is largely thanks to him. When Pierre departs in 2018, he will leave behind a sound, flourishing company.”

Theatre of the World, subtitled A Grotesque Stagework in Nine Scenes, is loosely based on the life story of 17th century Jesuit scholar and polymath, Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680). His investigations, progressive at the time, concerned various subject matter including the civilisations of ancient China, music, mathematics and Egyptian hieroglyphics. During his lifetime he was a renowned for his supposed scientific discoveries, amassing an enviable following. He was regarded as “the last man who knew everything” – both contradictory and ironic, as only later was he to be revealed a charlatan. “He made up a lot of things which makes him totally impossible for scientific research, but very valuable for the artist”, says Louis Andriessen of Kircher.

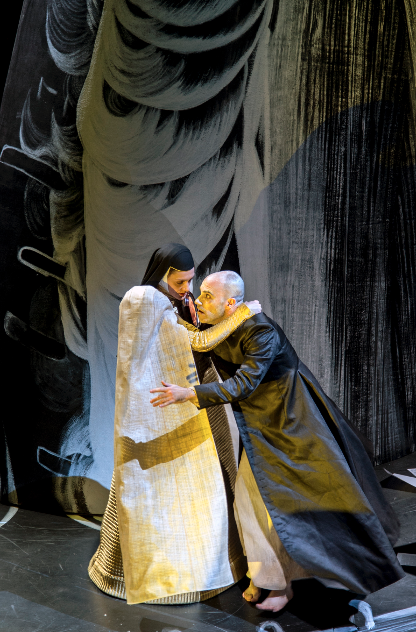

Rare it may be for a Jesuit scholar and a trio of witches (an allusion to Macbeth?) to find themselves at the same party, but Theatre of the World delivers. In the operatic treatment of this narrative, Kircher travels through time and space, during which his own intellectual achievements are reviewed. He is accompanied on his journey by Janssonius, his Amsterdam publisher, Pope Innocenzo XI and what appears to be an inquisitive young boy. The suggestion made is that he is a reflection of a young and effervescent Kircher, however he is later exposed to be the devil. The grotesque sub-theme is increasingly intensified through regular visits from the three witches – in sleazy dominatrix attire – and a Roman executioner. Perhaps less of a grotesquerie, Kircher’s lifelong muse, the Mexican nun and poet Sister Juana Ines de la Cruz also makes an appearance. History tells us that she and the Jesuit maintained long distance correspondence and was the platonic love interest of the scholar. For Andriessen, this served to represent desire and comfort in this operatic context, both out of reach for Kircher.

Eventually natural illness and old age ensure the scholar’s demise in real life. But is Kircher of the opera blessed with a peaceful death? No chance. In true homage to the genre, Andriessen again lurches towards the grotesque and has Kircher’s heart ripped out by the hangman and eaten by the devil, formerly the young boy who is played by a soprano. It is at this point that the haunting figures of four intellectual titans Leibniz, Voltaire, Descartes and Goethe enter and question the validity of Kircher’s scientific discoveries. They eventually arrive at the conclusion that only his name will be remembered.

An aspect of Andriessen’s work, which has remained a constant throughout his operatic career, is his propensity to use unconventional orchestral ensembles. Theatre of the World is a prime example of this. Andriessen lures his audience away from the traditional formalities and musical conventions of opera that inhabit the minds of many opera enthusiasts and introduces them to a new sound world by way of unfamiliar ensembles. Unlike most opera orchestras, the string section here assumes a secondary role. Generous sonorities are still provided, however Andriessen uses them sparingly and upon the arrival of select characters. Through his marshalling of the electric bass guitar and synthesisers, and the decision to idiosyncratically weight the ensemble with brass and percussion, his opera is wax-sealed by his musically ‘in-your-face’ trademark.

The eclectic instrumentation allows for Andriessen to successfully migrate from one musical idiom to another with fluidity and ease. Continuous fluctuation between musical styles and mood within this work is a key to the compositional technique. The opening trombone motive is reminiscent of Renaissance music, whilst vocal duets scream 18th century opera. Perhaps jarringly, Andriessen opts for the jazz idiom upon the arrival of the witches who are sexually suggestive and far removed from the Shakespearean model. Starkly and juxtaposed with this, rich melodies of Mahlerian vintage and warm Wagnerian textures complement the presence of Sister Juana, spinning an ethereal soundscape. This concoction of styles reflects the narrative and the contrast between the real and unreal. “He is a very fascinating figure because we don’t really know a great deal about him. His work and his life are a mixture of fact and fiction, and you are not really sure what is fact and what is fiction. I think that is the whole point about Kircher”, says Audi.

Stage design and animation for Theatre of the World were envisioned by the Quay Brothers. The duo from America, influential for their stop-motion animation, constructed the staging upon the ground where the stall seating formerly sat. Although being an unusual set placement, the crescent-shaped seating plan surrounding the stage produced an intimate atmosphere and a sense of true immersion. Enhancing this, the orchestra’s adjacent placement to both the stage and audience completely engulfed of all corners of the theatre in music and drama.

Behind the set hung a screen which curtained off the stage, onto which animation from the Quay Brothers was projected. Disappointingly, the intricacy of the somewhat ghoulish video seemed completely veiled behind the action taking place on the stage. Upon consciously focusing on the projection, one could argue that incoherence dominated and that it failed to contribute to the clarity of the work’s main theme. That being said, its successes lay in its emotional darkness.

To further demonstrate Kircher’s intellect and to reflect his linguistic capabilities, Helmut Krausser’s libretto continuously shifted between Middle Dutch, English, Italian, German, Spanish, French and Latin. A unique idea in post-modern opera and a vehicle through which Krausser could demonstrate his own talents, however audiences might have found the conspicuous and regular change of language disconcerting. That aside, projected surtitles in both Dutch and English brought some measure of clarity to what was possibly an opaque narrative.

Theatre of the World was well received by critics in the UK and USA, however two resounding criticisms concerned the lack of clarity in the storyline. Admittedly, the opera does prove difficult to follow at times, and may require a larger degree of familiarity with the synopsis than would be needed for the average Mozart favourite. “Krausser’s libretto, which veers between German, English… combines intellectual pretension with incoherence to irritating effect”, writes Shirley Apthorp for The Financial Times. There were also other issues. Regarding the ubiquitous animation, Andrew Clements for The Guardian writes that the “strangely incoherent video by the Quay Brothers is cluttered and busy, and doesn’t make an already tangled narrative any easier to follow.”

Despite these concerns, Andriessen’s craft, the immersive set design and quality of the musicians’ performance left most critics impressed. Clements comments “His pungent reedy soundworld is darker than usual, but its striding, jazzy ostinatos, sweet-sour chorales and early music vocal writing, as well as the lightning-quick references to a range of other musical styles, are as instantly identifiable and exhilarating as ever.”

Via this combination of varying textures, beautiful melody, styles and an immaculate performance, a former Andriessen virgin has been left aroused to inspiration by the range of possibilities. His stature as a leading compositional figure is deserving and one can admire the rich collaboration of art-forms in this production. Theatre of the World is a true asset to the body of contemporary opera and an important addition to Andriessen’s oeuvre.

I leave the theatre musing about Kircher, a man I hadn’t heard of only two hours before. The last man who knew everything? I’m not so sure. A lesson learned is always, always doubt a scholar.

Now, which way to the station?