Resonating Rhythms: Exploring the Enchanting World of the Sitar

The sitar, with its enchanting sound and intricate melodies, holds a revered place in the realm of Indian classical music. This stringed instrument, characterized by its long neck and resonating gourd, has captivated audiences for centuries. In this article, we embark on a journey to explore the essence and significance of the sitar in the rich tapestry of Indian classical music.

The origins of the sitar can be traced back to ancient India. Its predecessor, known as the veena, was a popular instrument in Vedic times, believed to have existed over 2,000 years ago. Over the centuries, the veena underwent transformations, giving rise to different variations across various regions of the Indian subcontinent. Eventually, the sitar emerged as a distinct instrument with its own unique character and tonality.

The word “sitar” is derived from the Persian word “seh-tar,” which means “three strings.” Originally, the sitar had only three playing strings, but it later evolved to include a total of 18 or 19 strings. The sitar we know today is the result of continuous refinement and innovation by skilled artisans and musicians.

The sitar gained prominence during the Mughal era in India, particularly in the 16th and 17th centuries. It found favor among the royal courts and nobility, where it was regarded as a symbol of sophistication and elegance. The patronage and encouragement from the Mughal rulers greatly contributed to the development and popularity of the sitar.

The renowned musician and composer Amir Khusro, who lived during the 13th century, played a significant role in shaping the sitar’s structure and contributing to its repertoire. Khusro’s contributions to Indian classical music were instrumental in establishing the sitar as a prominent instrument in Hindustani (North Indian) classical music.

It was during the 18th and 19th centuries that the sitar underwent further modifications. The addition of sympathetic strings, which run beneath the frets and resonate sympathetically with the played strings, gave the sitar its distinctively rich and vibrant tonal quality. These sympathetic strings enhance the resonance and provide a unique depth to the sitar’s sound.

Today, the sitar is celebrated as one of the most iconic instruments of Indian classical music. It has evolved into various playing styles and techniques, each with its own distinct characteristics and nuances. As we dive deeper into the anatomy and playing techniques of the sitar, we will gain a deeper appreciation for its intricate craftsmanship and the immense skill required to master this extraordinary instrument.

Anatomy of a Sitar

To truly appreciate the sitar and its intricacies, it is essential to understand its physical structure and the significance of its various components. Let us delve into the anatomy of this remarkable instrument.

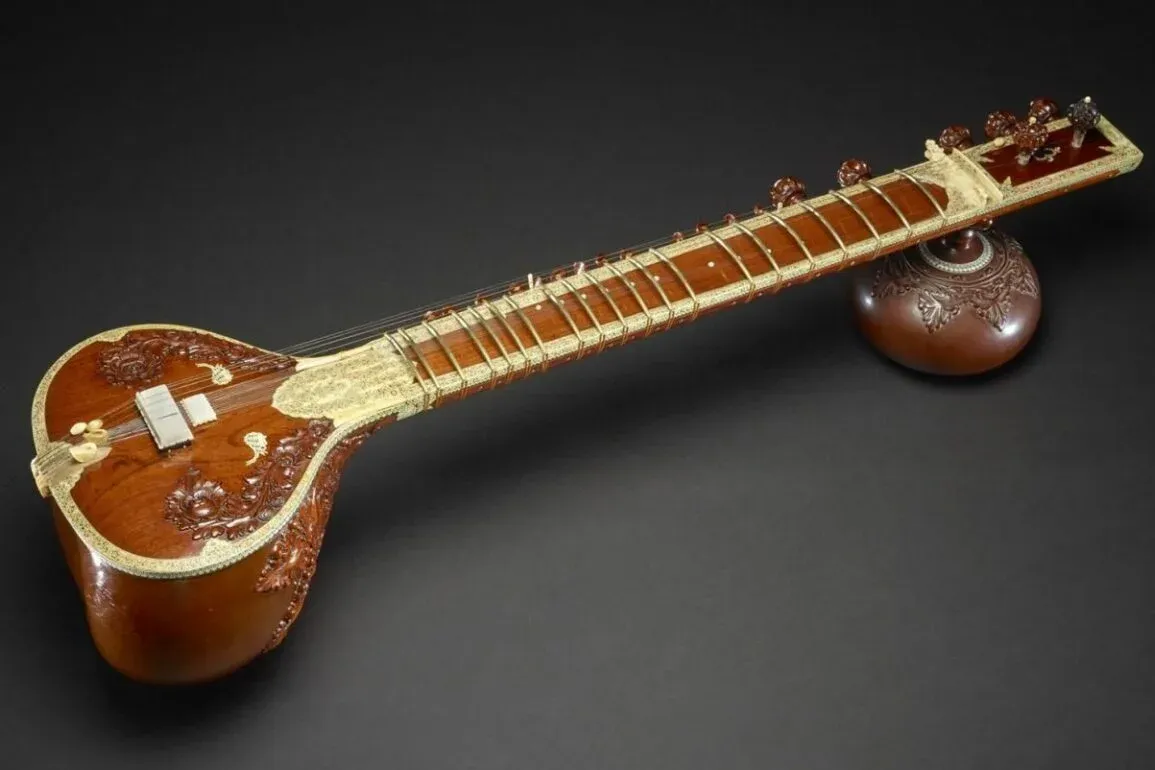

The sitar consists of several key components that work together to create its distinctive sound. The main body of the sitar is typically made of seasoned teak wood, known for its durability and tonal qualities. It is shaped like a pear and is hollow, allowing sound to resonate within its chamber.

Atop the main body of the sitar is a large, round resonating gourd, known as the “tumba” or “toomba.” This gourd acts as a natural amplifier, enhancing the resonance and depth of the sitar’s sound. The tumba is carefully crafted from dried pumpkin or a wooden replica, meticulously carved and decorated to reflect the aesthetic appeal of the instrument.

The sitar’s neck, known as the “dandi,” extends from the main body and is usually made of seasoned tun wood. It is long and slender, allowing for the placement of numerous frets and sympathetic strings. The dandi is adorned with intricate carvings and inlays, showcasing the craftsmanship and artistry of the instrument.

One of the defining features of the sitar is its movable frets, known as “pardas” or “meend.” These metal frets are tied onto the neck with a combination of wax and thread, allowing the musician to adjust the intonation and create microtonal variations. The positioning of the pardas determines the scale or raga that can be played on the sitar.

Beneath the frets are the main playing strings, typically seven in number, which are made of steel. The sitar has two main melody strings, known as the “baaj” or “dha” strings. These melody strings are plucked by the right hand, while the left hand presses the frets to produce different notes. The remaining strings are drone strings, which resonate sympathetically with the played strings, adding a unique harmonic dimension to the sitar’s sound.

In addition to the main playing strings, the sitar also features sympathetic strings, referred to as “taraf” or “tarab” strings. These strings run beneath the main playing strings and pass over small bridges, which are affixed to the sitar’s body. When the main strings are played, the sympathetic strings vibrate in harmony, producing an ethereal and resonant effect.

The sitar is played using a combination of techniques. The right hand plucks the strings with a metallic plectrum, known as the “mizrab.” The mizrab is worn on the index or middle finger, allowing for swift and precise plucking of the strings. The left hand applies pressure on the frets, bending the strings to produce subtle microtonal variations and expressive slides known as “meend” and “gamak.”

The intricate design and craftsmanship of the sitar, combined with its movable frets, sympathetic strings, and unique playing techniques, contribute to its distinctive sound and versatility. It is an instrument that demands patience, skill, and years of dedicated practice to master.

Playing Techniques and Styles

The sitar, with its intricate design and unique structure, offers a vast range of playing techniques and expressive possibilities. In this section, we will delve into the melodic capabilities of the sitar, exploring the techniques and styles associated with this magnificent instrument.

One of the fundamental techniques of sitar playing is known as “meend.” Meend involves sliding the left hand’s fingertip along the string, smoothly transitioning from one note to another. This technique enables the sitarist to produce fluid melodic phrases and graceful glissandos, adding a mesmerizing quality to the music.

Another essential technique is “gamak,” which involves ornamenting a note with rapid, delicate oscillations. Gamak adds intricate embellishments to the melody, infusing it with subtle nuances and emotional depth. It requires precise control and dexterity, allowing the sitarist to convey the intricate nuances of each raga.

The sitar offers a vast array of melodic possibilities through its movable frets. By altering the positioning of the frets, the sitarist can access different scales, or ragas, each with its distinct character and mood. This allows for endless creativity and improvisation during performances, as the musician explores the subtle variations and microtonal shades within each raga.

The sitar is deeply rooted in the two main gharanas, or musical schools, of Hindustani classical music: the Imdadkhani and Vilayatkhani gharanas. The Imdadkhani gharana, founded by Ustad Imdad Khan, is known for its virtuosic playing techniques, intricate melodic patterns, and complex rhythmic structures. The Vilayatkhani gharana, established by Ustad Vilayat Khan, is celebrated for its soulful and emotive playing style, focusing on melodic intricacies and lyrical expressions.

Within these gharanas, sitarists develop their unique styles and interpretations. Some emphasize the technical aspects of sitar playing, showcasing their virtuosity through fast-paced, intricate compositions. Others focus on exploring the emotional depths of each raga, creating soul-stirring melodies that tug at the heartstrings of the listeners. The beauty of the sitar lies in its ability to adapt and convey a vast range of emotions, making it a truly expressive instrument.

Over the years, the sitar has also ventured into fusion genres, collaborating with musicians from different backgrounds and cultures. The incorporation of the sitar into various world music genres and fusion experiments has expanded its sonic palette and global reach. The instrument’s versatility and adaptability continue to fascinate artists and audiences alike, bridging musical traditions and transcending cultural boundaries.

As we reflect upon the playing techniques and styles associated with the sitar, we gain a deeper appreciation for the skill and artistry required to master this extraordinary instrument. The sitar’s rich tonality, melodic flexibility, and expressive possibilities make it an integral part of the Indian classical music landscape.

Influence and Global Reach

The sitar, with its mesmerizing sound and unique melodic capabilities, has not only left an indelible mark on Indian classical music but has also made a significant impact on the global music landscape. In this final part of our exploration, we will delve into the influence of the sitar, its global reach, and its enduring legacy as a symbol of India’s rich cultural heritage.

One of the most iconic figures in sitar history is the legendary musician Pandit Ravi Shankar. With his virtuosity and innovative spirit, Pandit Ravi Shankar played a crucial role in introducing the sitar to Western audiences. His collaborations with renowned musicians such as George Harrison of The Beatles and his performances at major music festivals brought the sitar into the mainstream consciousness of the Western world.

The integration of the sitar into Western music, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s, marked a significant cross-cultural exchange. The sitar’s distinct sound and mystical quality captured the imagination of Western artists, inspiring them to explore new musical avenues and experiment with fusion genres. The sitar’s influence can be heard in iconic songs like “Norwegian Wood” by The Beatles and “Paint It, Black” by The Rolling Stones, among others.

Beyond its impact on Western music, the sitar has also gained popularity in world music genres and fusion experiments. Musicians from various cultures have embraced the sitar’s unique tonality and incorporated it into their compositions. The instrument’s adaptability and versatility have allowed it to blend seamlessly with diverse musical styles, creating transcultural collaborations and captivating audiences worldwide.

In the realm of Indian classical music, the sitar continues to hold a cherished place. Renowned sitarists such as Ustad Vilayat Khan, Pandit Nikhil Banerjee, and Pandit Ravi Shankar have pushed the boundaries of sitar playing, expanding the repertoire and elevating the instrument to new heights of virtuosity and expression. Their contributions have inspired generations of musicians, ensuring the sitar’s enduring legacy within the classical music tradition.

Furthermore, the sitar’s influence extends beyond the realms of performance. It has become an iconic symbol of Indian culture, representing the rich heritage and artistic traditions of the country. Its image adorns album covers, posters, and artwork, serving as a visual representation of the enchanting melodies and timeless beauty of Indian classical music.

As we conclude our exploration of the sitar, we are reminded of its significance as a cultural ambassador, bridging musical traditions and fostering a deeper appreciation for Indian classical music worldwide. The sitar’s unique timbre, intricate melodies, and evocative playing techniques continue to captivate audiences, transcending time and cultural boundaries.