Putting Bach into Tango

It was the birth centenary of larger-than-life Argentine tango composer, bandoneon player, and arranger Astor Piazzolla (11 March 1921 – 4 July 1992) last month.The Strad magazine carried a tribute article “How should we interpret tango music?” a guide to classically-trained violinists on how to tackle this music genre. Yet again, I was struck by how much classical music had meant to Piazolla while growing up. The Todo Tango website published a first-person account of Piazzolla’s recollections of his childhood in New York.

“I attended four schools until I finished grade school. They expelled me for quarrelling. But at one of them I found music: A teacher used to play records for us as examples. She made us listen to the Brahms’ third symphony, or the second movement of a symphony by Mozart. And at the next class we had to recognize each one of them.”

This would have been before he turned twelve. As he puts it, “I found it but I didn’t discover it. I didn’t pay attention to the explanations. I couldn’t stop laughing and making my schoolmates laugh. I discovered it later when I was 12 years old.” This is what then happened: “We lived in a very long house and there, at the back, beyond a courtyard there was a window and, from there, the sound of a piano was heard. It hypnotized me, I stood still beside it. Later I came to know it was a piece by Bach and that the pianist practiced nine hours a day. He was Bela Wilda and soon he became my teacher.”

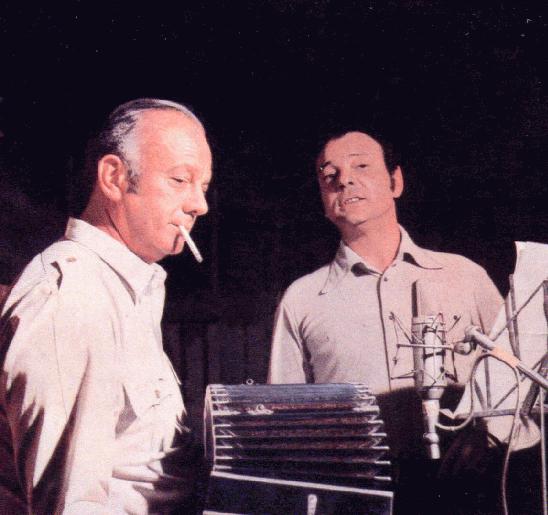

I found this part of Piazzolla’s account really touching. Here was a neighbour who just happened to be going through his daily grueling practice regimen, but across a courtyard and through an open window, a little boy heard it and was “hypnotized.” Isn’t that something? There’s really no telling who or what can inspire whom, or how or when. Bela Wilda was a Hungarian classical pianist who had been a student of Russian virtuoso pianist, composer, conductor and pedagogue Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1973). Piazzolla vividly recalled his first encounter with his teacher: “My father and I knocked at his door and when he opened it I was bewildered by his grand piano and the pack of Camel cigarettes he used to smoke.”

As Piazzolla came from a poor Italian immigrant family, a novel method of payment for piano lessons was arrived at: “As mom had no money and because she worked as a manicurist she agreed to care for his hands for free, of course, and twice a week bring him a dish of gnocchi or ravioli. My teacher loved pasta.”

Back at his home, he would listen to his father’s records of the tango orchestras of the great French-Argentinian singer, songwriter, composer and actor Carols Gardel (1894 – 1935) and Argentinian tango composer Julio de Caro (1899 – 1980). Thinking back on those days, Piazzolla was glad that his father “had those records and not ones cut by other tango men, in general, mediocre musicians.”

One of Piazzolla’s friends, fellow Argentinian Andrés D’Aquila played piano as well as the bandoneon (a type of concertina particularly popular in Argentina and Uruguay, a typical instrument in most tango ensembles) and taught it to Piazzolla.

Wilda later in his music classes, made him play Bach on bandoneon.

“He handed me the sheet music for piano and he showed me what I had to do and what I ought not to do. Very soon my father bought me [a bandoneon].”

Piazzolla told a colourful story of his first meeting with Gardel (going through a fire escape and a window to wake him up as the door was locked) in 1934 and even played a cameo role in the actor’s movie ‘El día que me quieras’ (‘The day that you will love me’) the following year. Gardel was sufficiently impressed with the teenaged Piazzolla’s bandeoneion playing to invite him to join Gardel’s performance tour, but his family wouldn’t let him as he was too young, much to Piazzolla’s dismay. But in retrospect it was a life-saving decision, as Gardel and his band would perish tragically in a plane crash while on that tour. Piazzolla would later remark with dark humour that had his parents allowed him to go on that tour, he would have “played the harp instead of the bandoneon.”

By the age of twenty, now in Argentina, Piazzolla could afford lessons in orchestration with eminent Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983) on the advice of Polish-American pianist Arthur Rubinstein (1887-1982). Piazzolla immersed himself in the scores of Stravinsky, Bartok, Ravel and others, rising early each morning to listen to the Teatro Colón orchestra rehearsals while continuing to play in tango clubs by night.

In 1943, he began piano lessons with Argentine classical pianist Raúl Spivak, and wrote his first classical works ‘Preludio No. 1 for Violin and Piano’ and’ Suite for Strings and Harps’.

As his tango career advanced, Piazzolla continued to study Bartók and Stravinsky and orchestra direction with German conductor Hermann Scherchen (1891-1966), searching for his own creative voice, composing several works along the way.

In 1953, his composition ‘Buenos Aires Symphony in Three Movements’ featuring two bandoneons in the orchestra so offended the audience that a fight broke out, but it nevertheless won Piazzolla a grant to study in Paris with the legendary composition teacher Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979). From her, he would learn counterpoint, which would prove useful to him later.

By then he was tired of tango music and tried to conceal that aspect of his past from Boulanger. But she saw that his genius lay in tango when she heard him play his composition ‘Triunfal’ and urged him back in that direction.

Back again in Argentina, his distinctive style would be nuevo (new) tango, incorporating jazz, extended harmonies and dissonance, counterpoint and fugue, and compositional forms such as the passacaglia, a cyclical bass line, and allowing musicians the freedom of improvisation.

Perhaps the most recognizable among his works is ‘Libertango’, a portmanteau of the words “libertad” (Spanish for liberty) and “tango,” symbolizing Piazzolla “liberating” himself from classical tango to tango nuevo.

Although an instrumental composition, in 1990 Uruguayan poet Horacio Ferrer added Spanish lyrics, his own poem ‘Libertango’. Almost every line cries out at the beginning “Mi Libertad” (My liberty), and one couplet seems to sum it up rather well: “Ser libre no se compra ni es dádiva o favor” (“Being free is neither a purchase, nor a gift, nor a favour”).

Something to think about, both on and off the dance floor.

This article first appeared in The Navhind Times, Goa, India.