Proofreading, Publishing and Piracy in the time of Beethoven

Happy 250th birthday this Wednesday, 16 December 2020, Ludwig! The world had such great plans to celebrate this milestone, but a minuscule virus put paid to all that. My reading marathon on Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) in his birth sestercentennial year continues to throw up the most fascinating trivia about him and his times. For example, he was beset by similar woes that bedevil the modern-day ‘author’.

Beethoven was extremely fussy about which works of his got published, in what order, and from which publisher. He would also be the first composer to be published constantly, from the beginning to the end of his mature work. In her article “International Dissemination of Printed Music during the second half of the Eighteenth Century”, Sarah Adams from Cornell University discusses how that period was a turning-point in the history of music publishing, following improvements in music printing techniques due to the extensive use of engraving. The development of engraving on pewter and copper plates made publishing quicker and cheaper. Music was inscribed in mirror-image on the plates by exceptionally skilled but terribly-remunerated artisans, and printed off on a handpress.

Music therefore began to get circulated more frequently in print rather than manuscript form, and as public interest and demand in music grew due to an expanding middle class and an ever-increasing number of amateurs and professionals hankering for new pieces to play, a large number of publishers went into business.

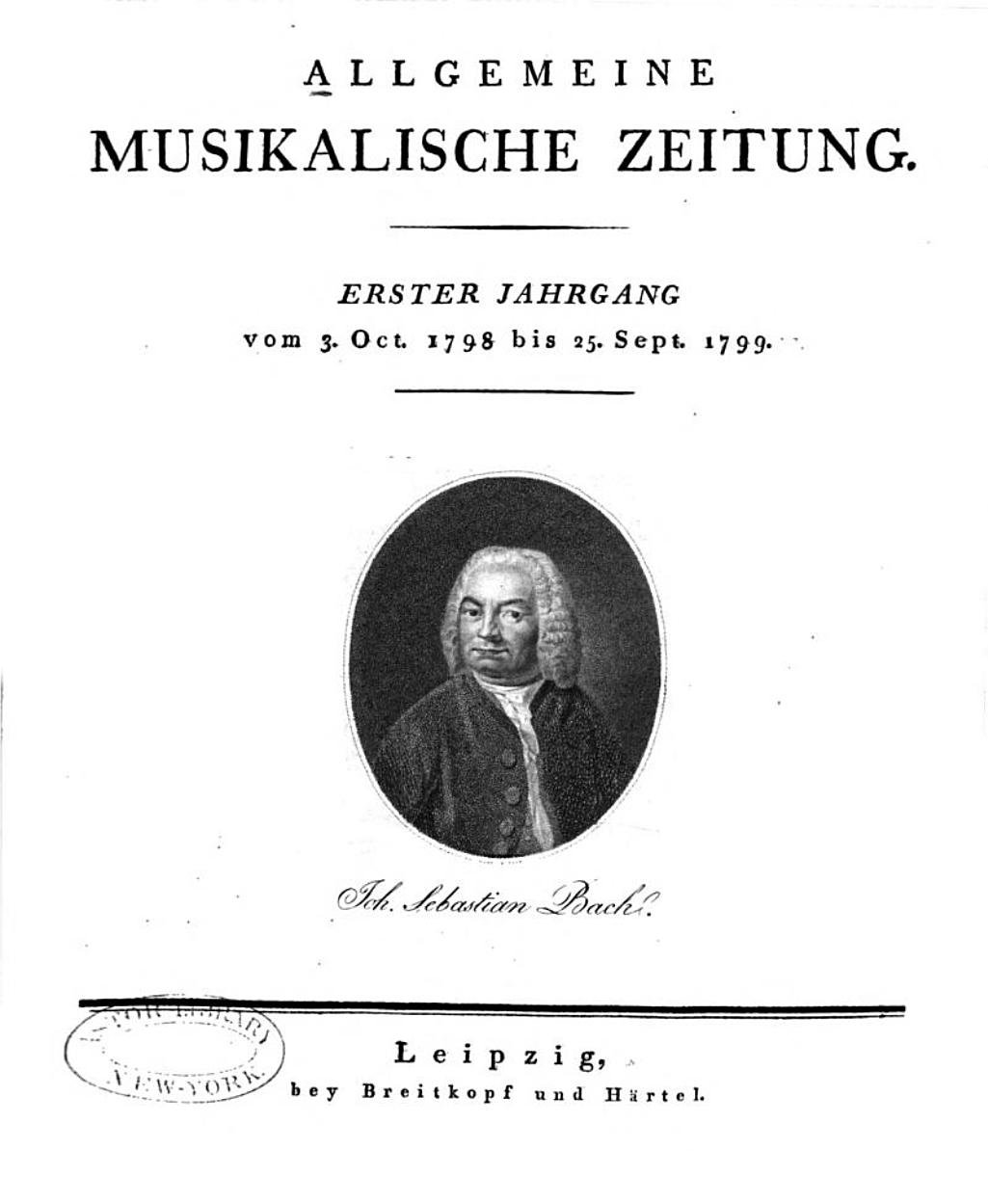

Some of those publishers are still thriving even today. Breitkopf and Härtel is the world’s oldest music publishing house, established in 1719 in Leipzig, with close editorial collaborations with besides Beethoven, also Haydn, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Chopin, Liszt, Wagner and Brahms. They also began an influential music review journal, the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung.

Simrock publishing house was founded in 1793 in Beethoven’s hometown Bonn by his horn-playing friend Nikolaus Simrock, undergoing several changes and mergers before being acquired by Boosey and Hawkes in 2002. Its list of published first editions is a ‘Who’s Who’ of composers: apart from 13 first editions for Beethoven, it includes Mozart, Haydn, Schumann, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Bruch, Dvořák and Suk.

Artaria, one of the most important music publishing firms of its time (founded in Vienna in 1770, Beethoven’s birth year) was dissolved in 1932, but in its heyday published more than 300 of Haydn’s compositions, which greatly enhanced its prestige, with Mozart, Boccherini and Beethoven using their services.

Once Beethoven had poured his creative energy to the fullest into a composition, he then regarded it as commercial property, deserving the best possible price on the most favourable terms. Of the literally hundreds of his letters that have survived, a major chunk deals with the mundane business of getting published: pitching a work, complaining about poor terms, bargaining, and correcting proofs. This is hardly surprising; he is perhaps the first composer whose income depended so much from being published, even more so after his crippling deafness gradually put paid to his career as a performer and to a lesser extent as a teacher as well.

But Beethoven rose to the occasion as quite an astute businessman, regarding publishing and all that it entailed as par for the course in which he wished to excel just as much as in his creativity.

Once he completed a work, Beethoven would offer it to one or more publishers. But before that he needed a copyist, someone who could legibly decipher his scrawl across the manuscript pages so that a publisher could make sense of them. One copyist, Wenzel Schlemmer, undertook that unenviable task for some twenty years.

But once a publisher accepted a work, the real pain of proofreading of invariably faulty engravings and endless corrections would ensue. In one instance, Beethoven found eight mistakes in one published work, corrected them and sent them to another publisher under the heading ‘Edition très correcte’. But in a further comedy of errors (typos), that heading was itself misspelt!

Royalties were unheard-of then; the publisher bought a work for a flat fee and would then hope to sell as many copies as possible, and as quickly as possible too, because piracy was a very real threat. As there was no copyright, any successful composer’s ‘hit’ work was highly susceptible to piracy. The ‘pirate’ could even be the copyist himself, who could clandestinely make another copy, secreted out to another publisher, sometimes even before the ‘legitimate’ one. The threat was so serious that Mozart had his copyists work only in his apartments, under his watchful eye.

Beethoven ranted and railed when he encountered pirated versions of his music, but as he didn’t really have the finance for lawsuits that could end up nowhere (piracy, plagiarism and forgery were regarded as reprehensible but not against the law), resorted to spluttering, threatening letters to errant publishers and to public notices in the newspapers. To be pirated was almost a back-handed index of one’s popularity and success.

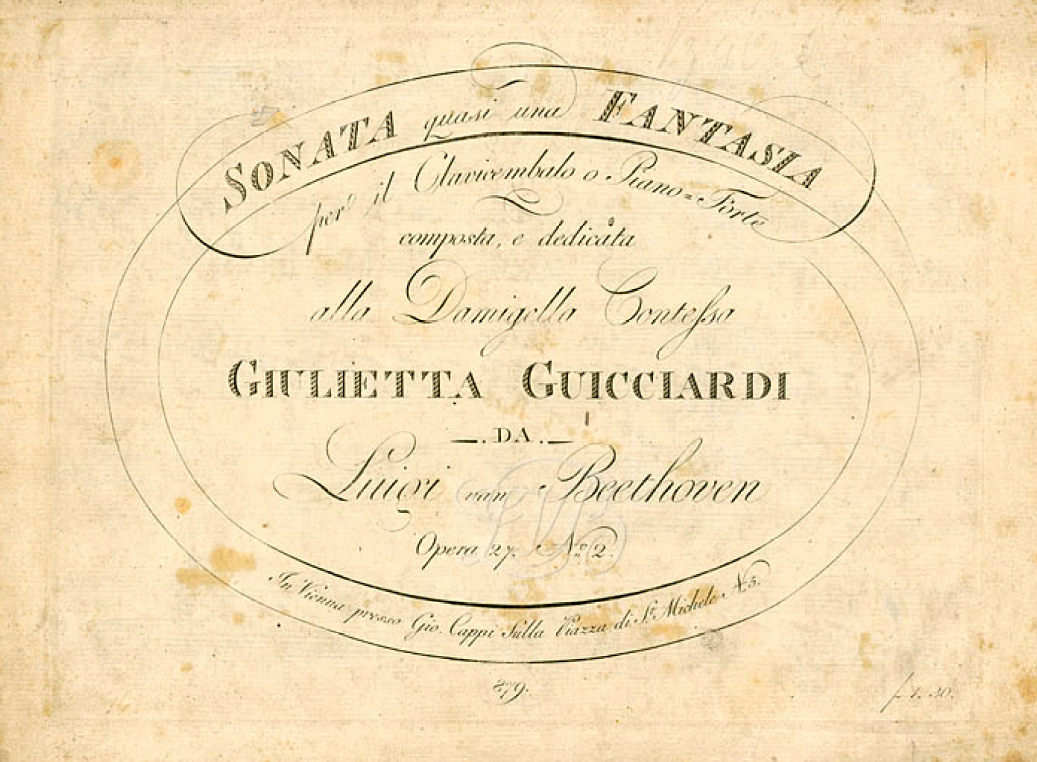

As payments for compositions were small (for instance, Beethoven settled for 100 florins for his First Symphony, a shockingly low price), one had to churn out a lot of music. This gives one a new perspective to the prodigious output of composers from that era; it was driven not just by creative juices but by having to put food on the table and pay bills. Ironically, short piano works might fetch a better price than say a symphony, concerto or bigger works, for purely commercial reasons.

One way (that Haydn used very profitably) of squeezing as much money out of a work was to give it to two or more publishers in different countries, each one having limited but mutually exclusive territory, so that one could be legitimately paid for the same work more than once. Beethoven followed suit, but then found that if he wanted to prevent pirates preying on his music, he’d have to get a given work published simultaneously in each country, no easy task in his time of really snail-mail and travel.

Another ploy Beethoven resorted to would be to offer a piece to the person who commissioned it and having pocketed his fee; he’d then defer publication but give that patron exclusive rights to the work in manuscript for a given time (usually six months, as he did with Prince Lobkowitz for his Third Symphony), and thereafter he could plug and sell it afresh.

Beethoven’s decision to appoint his brother Karl as his go-between to publishers was ill-advised, as Karl was arrogant and tactless. His letters to publishers (about which many complained) have to be read to be believed; it is a testament to their regard for Beethoven that they didn’t sever their contracts. One notable example of Karl’s unprofessionalism was when he sold his brother’s three piano sonatas (Opus 31) to a Leipzig publisher, despite Beethoven having promised them to another publisher, Nägeli. The brothers apparently “came to blows” in the street over the incident. Beethoven eventually forgave him (“After all, he’s my brother”) but gradually relieved Karl of that duty.

On the “tiresome business” of publishing, Beethoven grumbled in a letter to the publisher Hofmeister:

“There ought to be in the world a market for art, where the artist would only have to bring his works and take as much money as he needed. But, as it is, an artist has to be to a certain extent a businessman as well.”

True then, true today.

This article first appeared in The Navhind Times, Goa, India.