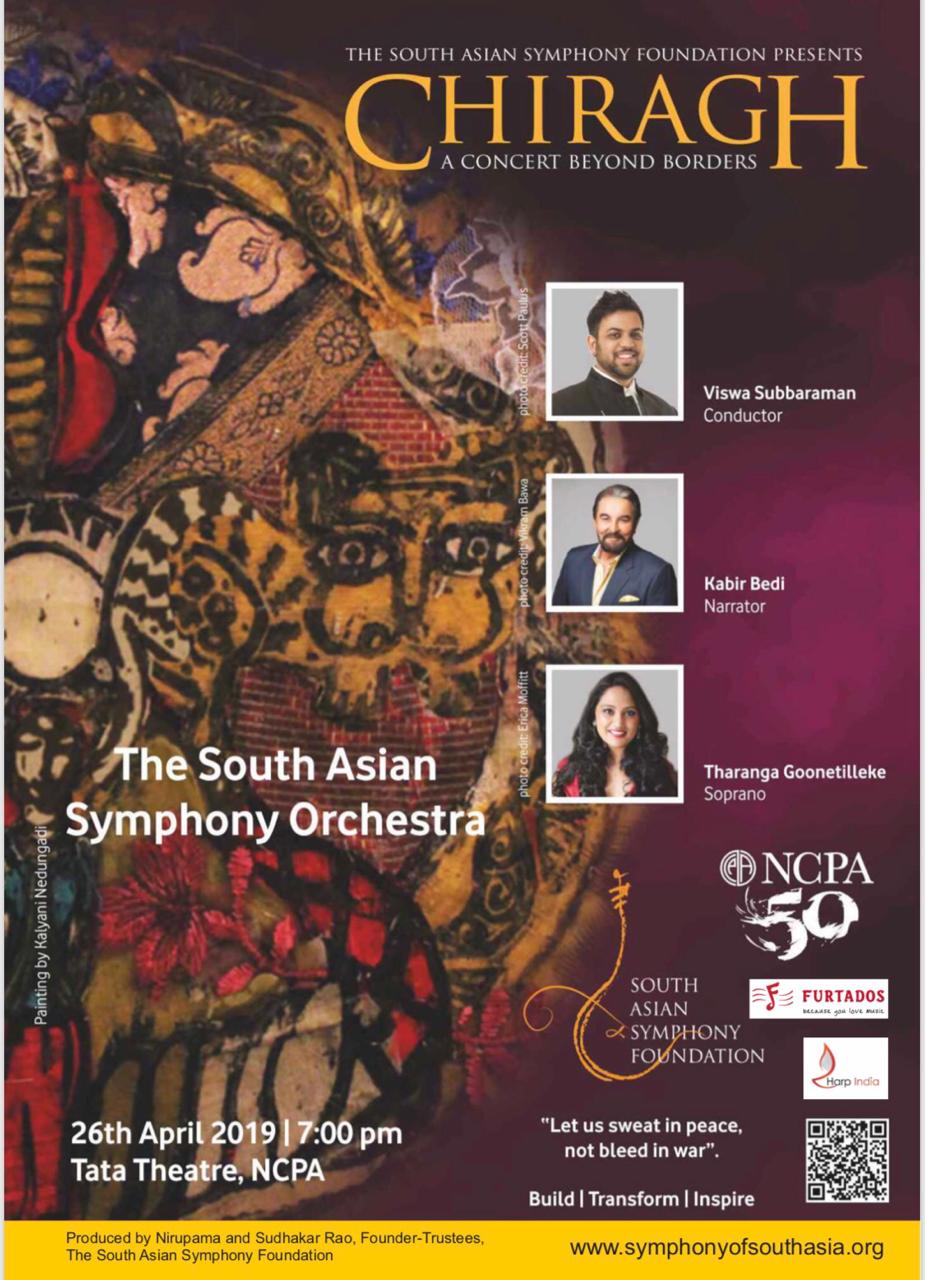

PLAYING FOR PEACE

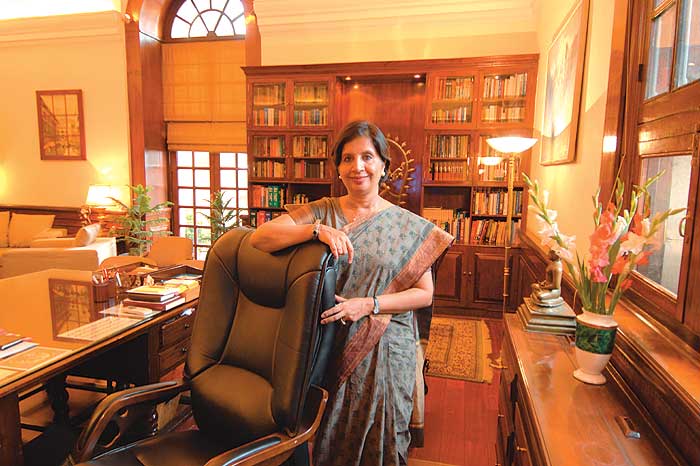

The South Asian Symphony Orchestra’s debut performance in India, slated for April 26th, is a significant event, and not just for musical reasons. It has brought the power of music to bind, to heal, and to create a climate of peace and goodwill among nations of the region. Appropriately enough, SASO’s founder-trustee is a diplomat of ambassadorial status, and India’s former Foreign Secretary. Nirupama Menon Rao, and her husband, former civil servant Sudhakar Rao, have envisioned, and now brought to fruition, this remarkable venture, which will see an ensemble of musicians from Afghanistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal, India, Sri Lanka, and the global South Asian diaspora, meet on the concert platform to present works from the Western art music repertoire, as well as a work especially commissioned for the occasion: Hamsafar: A Musical Journey Through South Asia.

The orchestra will perform under the baton of young Indian-American conductor, Viswa Subbaraman. Sri Lankan soprano, Tharanga Goonetilleke, will present arias from operatic works, and the programme will have a significant infusion of the rhythm and melody from the region’s rich folk music. A nice touch is the extra-musical element which features narration by Kabir Bedi, whose richly sonorous voice is well-known to audiences the world over.

The key players of SASO, both on and off stage, shared their personal musical journeys, and their vision of the role of the region on the international platform, in a series of interviews.

Priya Chaturvedi: SASO’s debut concert in Mumbai this April will feature a newly-commissioned piece, Hamsafar: A Musical Journey Through South Asia. What is the musical content and orchestration of this work?

Nirupama Rao: The piece is built as a number of short movements that encapsulate many of the countries represented in the orchestra. The music revolves around either folk music or popular music from each country, so the work is highly tonal. The incorporation of instruments native to some of the countries also gives the work a world music flair. The melodies incorporated in this work which been arranged by Lauren Braithwaite, who is on the faculty of the Afghan National Institute of Music, Kabul are:

- Aiyandiye (Sri Lanka) – Gunadasa Kapunge

- Allah Megh De (Bangladesh) – Bengali Folk Song

- Euta Manche Ko (Nepal) – Narayan Gopal

- Meera Joota Hai Japani (India) – Shankar Jaikishan

- Arsala Khan (Afghanistan) – Traditional Afghan

- Ta Zee Ling (Bhutan) – Traditional Bhutanese

- Lal Meri Pat Rakhiyo (Pakistan) – Ashiq Hussain

PC: The programme largely features Western art music works from the 19th century oeuvre (Beethoven, Mozart, Dvořák). What went into the repertoire choice?

NR: The orchestra’s mission is to build bridges between the countries represented, as well as to open a window to the West for a globalizing South Asia. Our goal is to continue to offer a mix of Western music, as well as the music of our countries arranged for orchestra. Another work in the repertoire that is being premiered is a Hindi film song from the 50s, ‘Bhadke’, that has been specially orchestrated by Kamala Sankaram, the Indian-American composer.

PC: Following on the previous question, will SASO be looking at including genres of music indigenous to South Asian musical cultures in future performances?

NR: There is no question that the orchestra will continue to look at building the repertoire for orchestra from South Asia. Our hope is to not just recreate the music of South Asia as some fusion experiment, but to allow the composers of South Asia and South Asian heritage to have a true voice in composing for orchestra in the same way that Japan did for Takemitsu or China did for Tan Dun or Huang Ruo. We need to help build our own voices into international presences and to positions of eminence. I also plan to commission 30 well-loved songs from the region for orchestra. This will be the initiation of our South Asian Songbook.

Priya Chaturvedi: Your operatic repertoire is a wide one, covering, stylistically, works from the early Classical (Gluck, Mozart), Romantic (Ravel, Puccini) and Modern (Britten, Joplin) periods of composition. Is there any one style and/or composer you have a particular affinity for?

Tharanga Goonetilleke: Any role that is well written for a full lyric soprano is one that I would embrace. As for style, having studied in depth the different styles, I am comfortable moving from one to another seamlessly. But what really makes me more partial to some roles than others, are the operatic characters themselves; some resonate with me more than others. I would say Mimi in La Bohème is one such character. Both Susanna and the countess from the Marriage of Figaro are characters that resonate with me as well, but are by Mozart and not by Puccini- very different in period and style. The list can go on. However, I would have to say, Mozart does have a slight edge over most composers for me, as his works thrill me as well as challenge me simultaneously at every given moment within a role.

PC: What led to your choice of the three arias you will be performing at the SASO concert, which feature the classicism of Mozart, Félicien’s unique idiom, called ‘Oriental exoticism’ and Dvořák’s Romantic nationalism?

TG: This concert is unlike any concert I have performed in that the orchestra itself is one that has never played together under one baton before. When selecting the repertoire I had to not only give consideration to what I would like to perform as a soloist but also what is practical to be put together by every individual on the stage within a very short period of rehearsal time. Collaborations require a special chemistry and synchronization that sometimes take years to develop. The selected Mozart and the Dvořák pieces are a happy medium between what could work out practically for the orchestra and two pieces I happen to love. The Félicien’s piece was hand-picked by Ambassador Rao who is the force behind this entire endeavour, as this happens to be one of her favourite works. I also believe that these three pieces will not only be welcomed by members of the audience that are very familiar with the operatic repertoire but also the first-time listener.

PC: As the first singer from your country to be accepted at the prestigious Juilliard School, do you foresee a greater presence of Western art music performers from the South Asia region on the international music scene?

TG: As it turns out, the recent statistics show that I am the only South Asian singer (not just Sri Lankan) to be accepted to Juilliard. In total there have been six South Asian Juilliard graduates who range from conductors, pianists, actors and more. I am humbled and honoured to represent not just my homeland but my fellow brothers and sisters of South Asia.

Yes, I do foresee a tremendous growth in Western music performers from our part of the world in the international music scene. I believe that exposure from one’s childhood itself to music both Western and/or Eastern has the power to swing a musician to develop into what they naturally are attracted to. That kind of exposure is very high all over the world today including in South Asia. Something as simple as having access to YouTube was not an option 20 years ago when I was a teenager growing up in Sri Lanka. Now, that’s definitely not the case. If there is exposure, curiosity inevitably follows and then a thirst for knowledge, and the resources to learn are not too far from one’s grasp if looked for in the right places. The future for South Asians in the Western music scene is certainly the brightest it has ever been.

PC: What have been the high points of your performance career till date? Is further exploring the works of modern Asian composers (like Kim’s ‘Garden by the Sea’) part of your future plans?

TG: If this question had been asked of me a couple of years ago, I would have probably answered; the first time I performed at Lincoln Center, New York City Opera or Carnegie Hall. But, I have to say, last year I had the very unique and most exhilarating performance of my life where the event itself brought me to realize why it is that we make music, after all. The performance was made possible by the African Prisons’ project where I had the tremendous honour to share my music with over 3000 inmates at the Luzira Maximum security prison in Uganda.

I believe as artists we have the tremendous scope and power to shape and mould the paths our careers can take. In the recent past, I have had the thirst to bring about different forms of art/music as well as the sciences together. As a result of this quest, in 2017 I was able to perform a recital in honour of women in science, while having my artwork (portraits) of women scientists that I myself was commissioned to make be displayed at the 5th anniversary of the Center for Women in Science at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada.

As for performing pieces by Asian composers, I am completely open to that. In fact, in June 2018 I performed a work by Sri Lanka composer, the late Premasiri Khemadasa, with the Sun Symphony Orchestra in Vietnam. I am also in conversation with two other South Asian composers; Lalanath de Silva (Sri Lanka) on a new piece that he will be composing for a performance in Chicago next year and Usman Riaz (Pakistan) on recording the theme song for the first hand-drawn animation movie of Pakistan ‘The Glassworker’ which is underway.

Priya Chaturvedi: Your open letter to the then-US President (Obama), featured in your blog, lays out very clearly your priorities and concerns about the role classical music should play in mainstream American life: its relevance in the area of diplomacy and building relations between countries; the misconception of its being an elitist art form; its value in music education. Could you expand on your views in these areas, especially in the South Asian context?

Viswa Subbaraman: I think fundamentally, great art – whether it’s South Asian, African, Western, etc. – holds a mirror to humanity. The act of making music or experiencing music with others allows us a connection that is almost impossible to replicate otherwise. In the South Asian context, I think we have spent so much time working towards developing the economy, the tech sector, etc. But, in doing so, much like in the US, we are losing sight of those activities that make us human. Aside from the fact that music has been shown to develop math skills, higher levels of pattern recognition while fostering that very creativity that companies are looking for, music in itself is part of what makes us “elevated” as people. One of the fascinating things I’ve found as a conductor that music crosses tribalism. When I moved to Paris, the French musicians I met did not care I was American, they cared that I was a musician. We had a common language, even though my French was terrible!

PC: Given India’s huge film industries, where song, dance and theatre come together on one platform, why, do you think, opera (which is quite similar), has remained out of the area of interest of Indian listeners?

VS: I have spent a lot of time thinking about this question. It is actually because of the similarities that I even had the idea to create my ‘Bollywood Fidelio’, though, as Ambassador Rao correctly pointed out, my Fidelio had more linkages with 1950s Tamil films. I think the reason opera has not become an area of interest in India is for a few reasons. First and foremost, the cost of producing and performing opera at the level we see in Europe and the West is incredibly high. (Though do let me know, I would love to bring a production to India). After that, I think there are the same problems we have in the US – ticket prices are high for the average goer, opera is usually in a foreign language, so one has to resort to subtitles to get the story across, and a lack of exposure to the art form. One of the challenges of any art music (and I include Hindustani and Carnatic music in this) is that it takes time to experience it. It is only with some exposure that the onion begins to be peeled and the incredible layers underneath the surface story telling of opera can even happen. I will say that there are many Indians who are incredible fans of opera. I had a wonderful conversation with Shyam Benegal about opera that made me have to go do some research.

PC: You have done significant work in conducting modern operatic works, such as those by Ades, Glass, Adams, to name some. How has the audience response been, considering that, in popular perception and taste, opera has remained largely a 19th century art form?

VS: What is truly interesting and lesser known is that the United States is leading the world in opera premieres. The sheer number of new operas being produced is magnificent, and I really believe that it is because of this that we are seeing a growth in opera attendance. One of the problems I alluded to above was that so many operas are in foreign languages. Most new operas in the US are in English, and they are beginning to tell stories that are directly related to audiences in the modern era. I was a part of a premiere at Opera Philadelphia that had to do with race relations in the United States. It sold out in Philadelphia, the Apollo theater in New York, and at the Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam. While the common perception is that opera is stuck in the 18th and 19th centuries, the art form is still truly alive. In fact, one of the premieres on our upcoming concert is by the amazing composer Kamala Sankaram who is also a very gifted opera composer who had a recent premiere at the Kennedy Center in Washington.

PC: As an orchestral conductor who has studied with Slatkin and Alsop, and been associated with ‘greats’ in the field, like Kurt Masur, Sir Colin Davis and Bernard Haitink, please share some of the highlights of your experiences.

VS: I think I could write books about this. I can say that what I learned from Maestros Masur, Haitink, Davis, Mehta, and Muti is that while we have the greatest jobs in the world, we also have the highest responsibility to the composer. That generation of conductor may be one of the last to truly take pride in the lineage of the music they perform. Maestro Masur could discuss any Brahms symphony without a score because the level of study he put in was incredible. (Frankly, all of whom I mentioned can do that). But more than knowing every note, they understood the tradition of what they did. Sir Colin Davis spent over one hour with me after every rehearsal simply to talk about whatever score I wanted to bring in. Maestro Haitink spent an hour talking to me about the real way to approach Mahler art songs. I was honoured to watch Maestro Mehta rehearse an entire Beethoven cycle in Florence. To me, nobody was more generous than Maestro Masur. He would talk about any detail of the music, but he also treated me like family. For him, music could change the world. He had been a part of that when he helped reunify Germany.