Philomena Thumboochetty: Portrait of an Artiste

The few, grainy, black-and-white photographs date from a century ago. Yet, together with the short ‘sketches’, and a couple of newspaper articles, they tell a compelling tale, and conjure up vivid images of a musician who became a legend in her lifetime, of a prodigious talent that flowered into magnificent maturity, and of an artiste who wore her laurels lightly, with grace, modesty and humility.

The first photograph is of a seven year old, violin in hand, already looking at home with her instrument. Philomena was named by her devoutly religious father, the ‘Huzur’ Secretary to the Maharaja of Mysore, after the saint to whom he was deeply devoted. A man of great vision as well as brilliance, he and his wife, early recognised their daughter’s unique gift, and put her under the tutelage of a musician-nun at a convent in Mysore. Talking about those beginnings, Philomena said, “I seemed to have taken to music like a fish to water.” So much so that, as a little girl, she was sent to study at the Calcutta School of Music, and took the fellowship examination offered by Trinity College London. The FTCL is the highest diploma level, and remains a benchmark of having attained a very high level of musical understanding and virtuosity in technique. That a teenager could not only appear for such an assessment, but play for the doughty examiner Dr Mistowsky, was an astonishing achievement. To cap that, she was awarded 98%, with Dr Mistowsky admitting that he had some difficulty in refraining from giving her the full score! A Conservatoire training was inevitable, but in the year 1929, and given her extreme youth, it was a brave decision on the part of her parents to send her to Europe. In her audition to the Paris Conservatoire, Philomena was one of the ten candidates from across the world to be selected for admission – the youngest, aged 16, and the first from India.

Paris, city of art, of artistes; a city that symbolised culture, the celebration of the intellect and the human spirit, deepened her musical understanding, even as it honed her formidable technique. Speaking of her classes with the great violin maestro, George Enescu, she said, “He was really my great master. He, I can almost say, moulded me into what I have been for the rest of my life.” Enescu was also the teacher of another brilliant violinist, who later came to have a very special connection with India – Yehudi Menuhin. Decades later, when Menuhin visited her in Bangalore, he told her, “You still play perfectly in tune”. Philomena had perfect pitch! While she was a student, she says, “Menuhin had already become a great star…”, but Punch magazine was to later, in its Silver Jubilee issue, remark that “Compared with her, Young Menuhin must yield…”! Light-hearted in vein, certainly, but an acknowledgement, nonetheless, of her standing amongst the stars of the day.

Given her long association with Trinity College London, it was in the fitness of things that her first public performance was in its College of Music in London. Her repertoire for that evening was an eclectic one, featuring Franck, Beethoven, Kreisler-Vivaldi and Bloch. She was billed as a “Hindu artiste”, probably because she performed (as she was always to do) in a sari, and named, in a plethora of initials “Miss P.T. F.T.C.L.”, in a combination of her initials and the fellowship acronym! Mention was also made, in glowing terms, of her royal patron, the Maharaja of Mysore, “a lover and patron of music who is one of the Vice-Presidents of this College”.

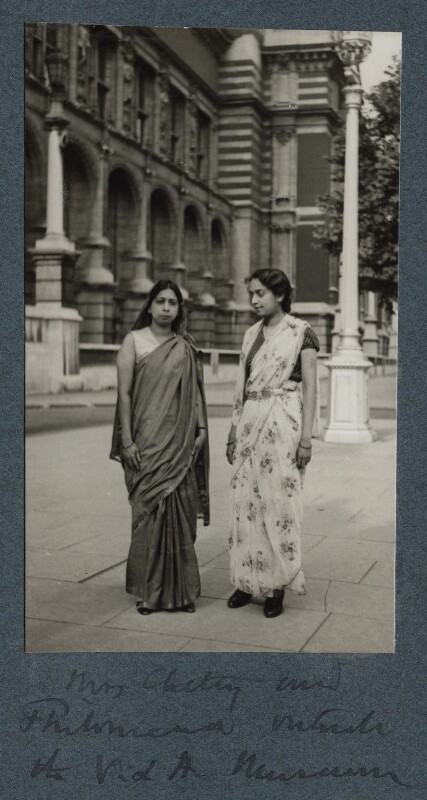

Another vivid image appears now: in 1934, Philomena and her mother were presented at the court of King George V and Queen Mary. The young musician wore, for the occasion, a gold embroidered red sari with a set of emeralds, while her mother was in purple and gold, set off by diamonds. What a glittering, exotic duo they must have been, bowing, not curtseying, to the monarch. It makes a pretty picture, but a superficial and cosmetic one compared to her 1935 recital at London’s Aeolian Hall. Her repertoire was a challenging one, including Philippe Gaubert’s Fantasie (making its London debut), and Bach’s Sonata for Violin in F major. Philomena’s second son, Ravi, told me that one of his most cherished memories is of his mother playing the Bach Sonatas “like a dream”. Critics reviewed the concert favourably: “There were moments of eloquence, and many of pure grace” (Sunday Times), “…Debussy was given with great poetical expression and charm” (Westminster Chronicle).

When she returned to India, some months later, it was to a tumultuous reception, with Bombay’s most eminent citizens and many from her own part of the country there to honour her. Besieged by the Press, Philomena had this to say: “I am anxious to give my first recital in Mysore before His Highness the Maharaja, as a loyal subject of his…” The concert took place in the following year at Mysore’s Jagan Mohan Palace, with the Maharaja and the Yuvraj, Jayachamaraja, in the audience. Playing with the Palace Orchestra under the baton of Otto Schmidt, Philomena presented her trademark eclectic repertoire, from the virtuosic Kreisler-Vivaldi Concerto, the spirited Saint-Saëns Havanaise, and the romantic Bruch Violin Concerto to shorter, appealing pieces like Brahms’ Hungarian Dance and Schubert’s Moment Musicale arranged by Kreisler. “One could not fail to note” says the anonymous author of the The Indian Fiddler Queen: A short Sketch of Philomena Thumboochetty, “and appreciate, the absence of mannerisms and the complete simplicity and naturalness of the method”.

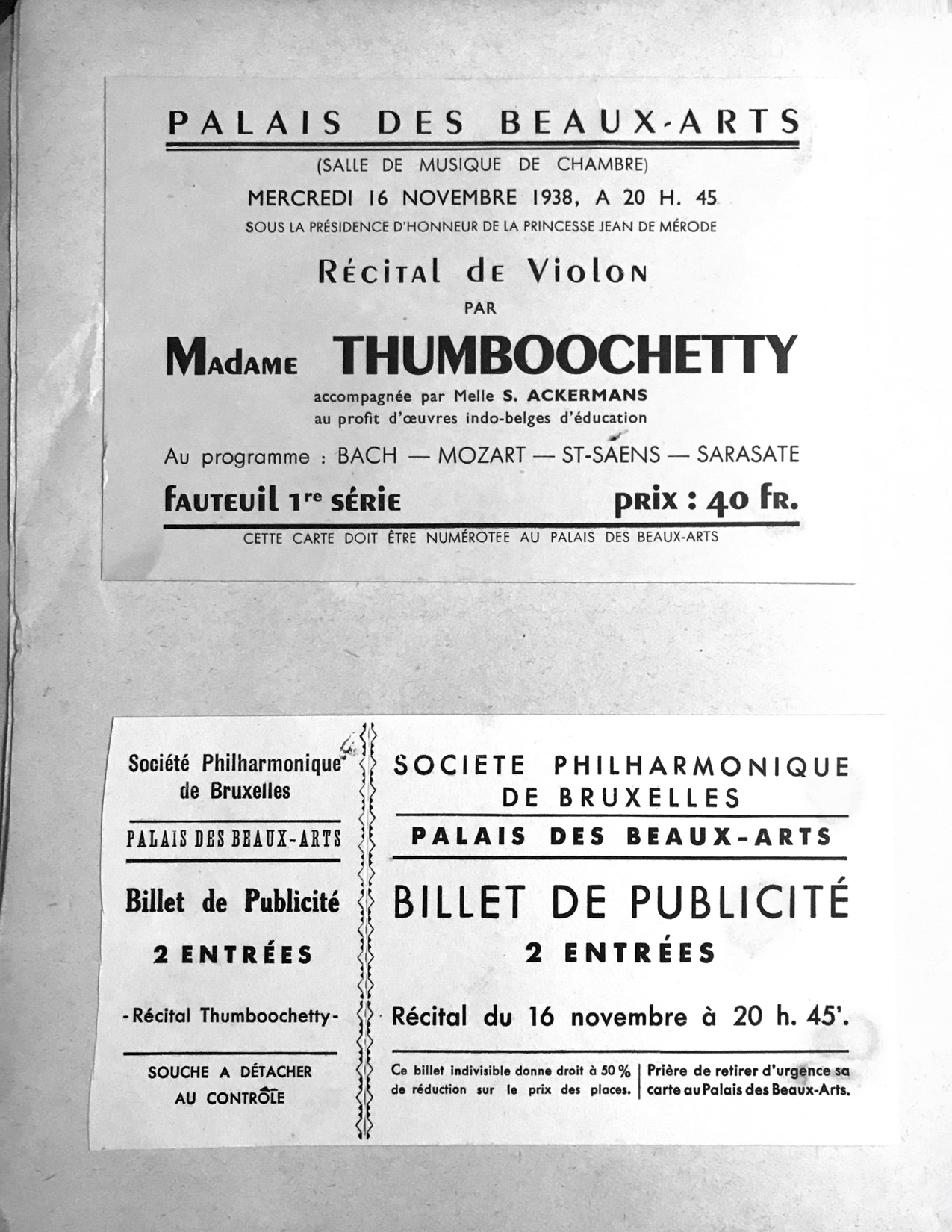

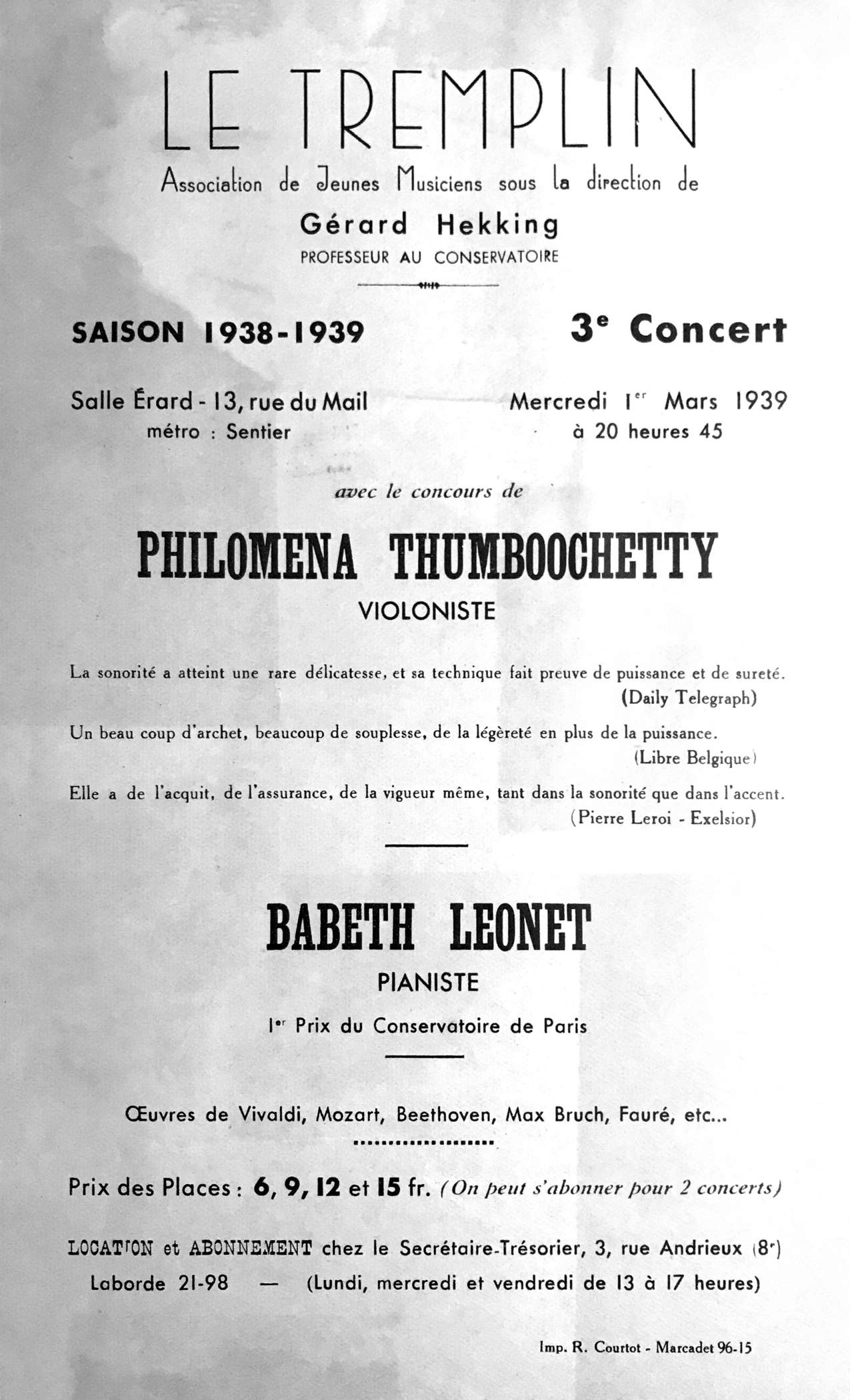

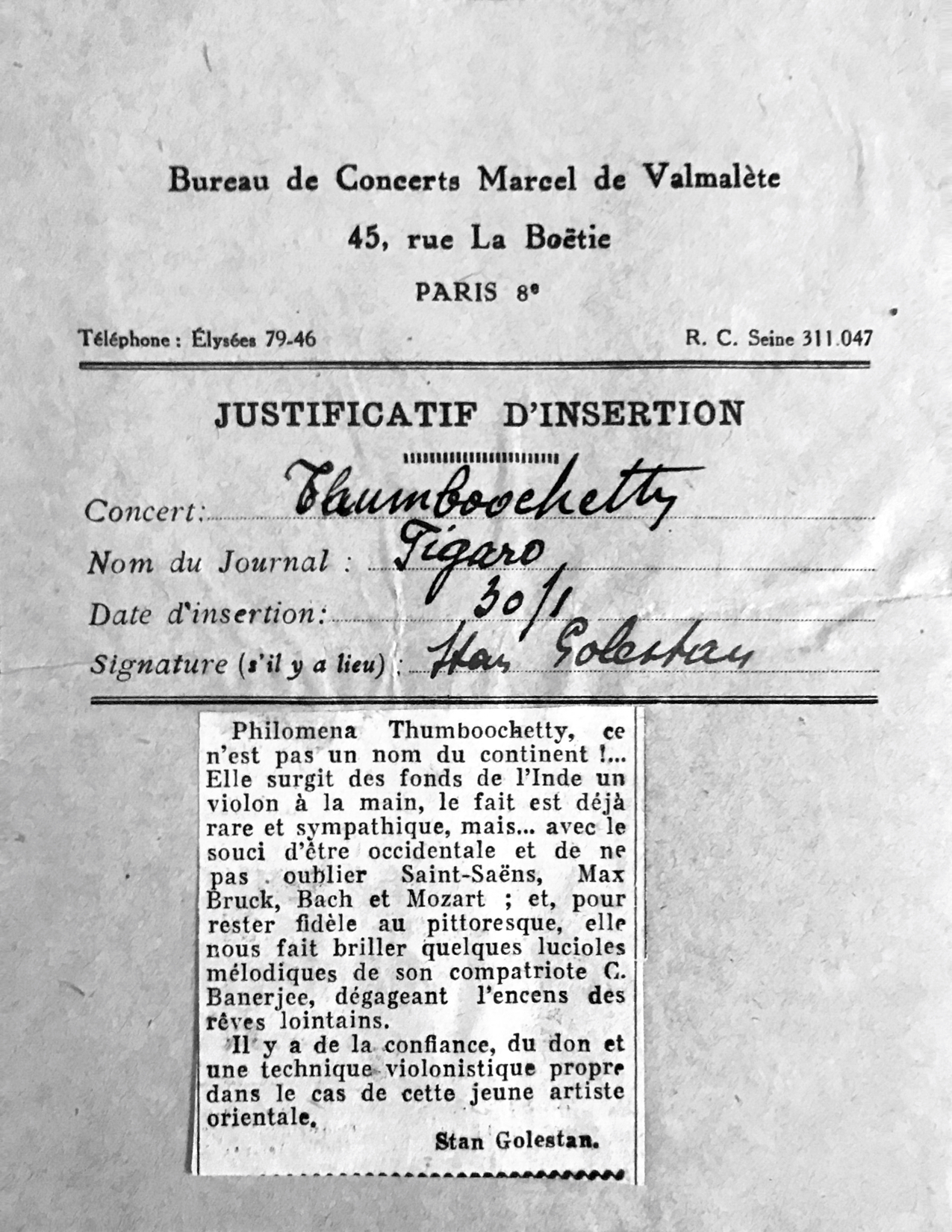

Was this the high point of her career? What came next? Marriage, to a family connection, Francis Thumboochetty in 1937, and a return to Europe to give more recitals. In 1940, the first of her five children was born. Ravi Thumboochetty, fills in the blanks: “My sister Chitra was born aurally challenged, taught to lip-read, sent to a special school, and then had a nervous breakdown”. In that economical retelling lies the world of sorrow and strain that the young parents had to cope with. “She was planning to go back to Europe to continue her career,” says Ravi, “but her family commitments did not allow that.” A special-needs child and a growing family anchored her to Bangalore. “There must,” says Ravi, “have been oceans of regret, but she never voiced it. She had no chip on her shoulder about her earlier fame, she did what she could to keep her music going. There were concerts in Bangalore, she continued to practice three hours a day almost to the end of her life, she performed when she could…”

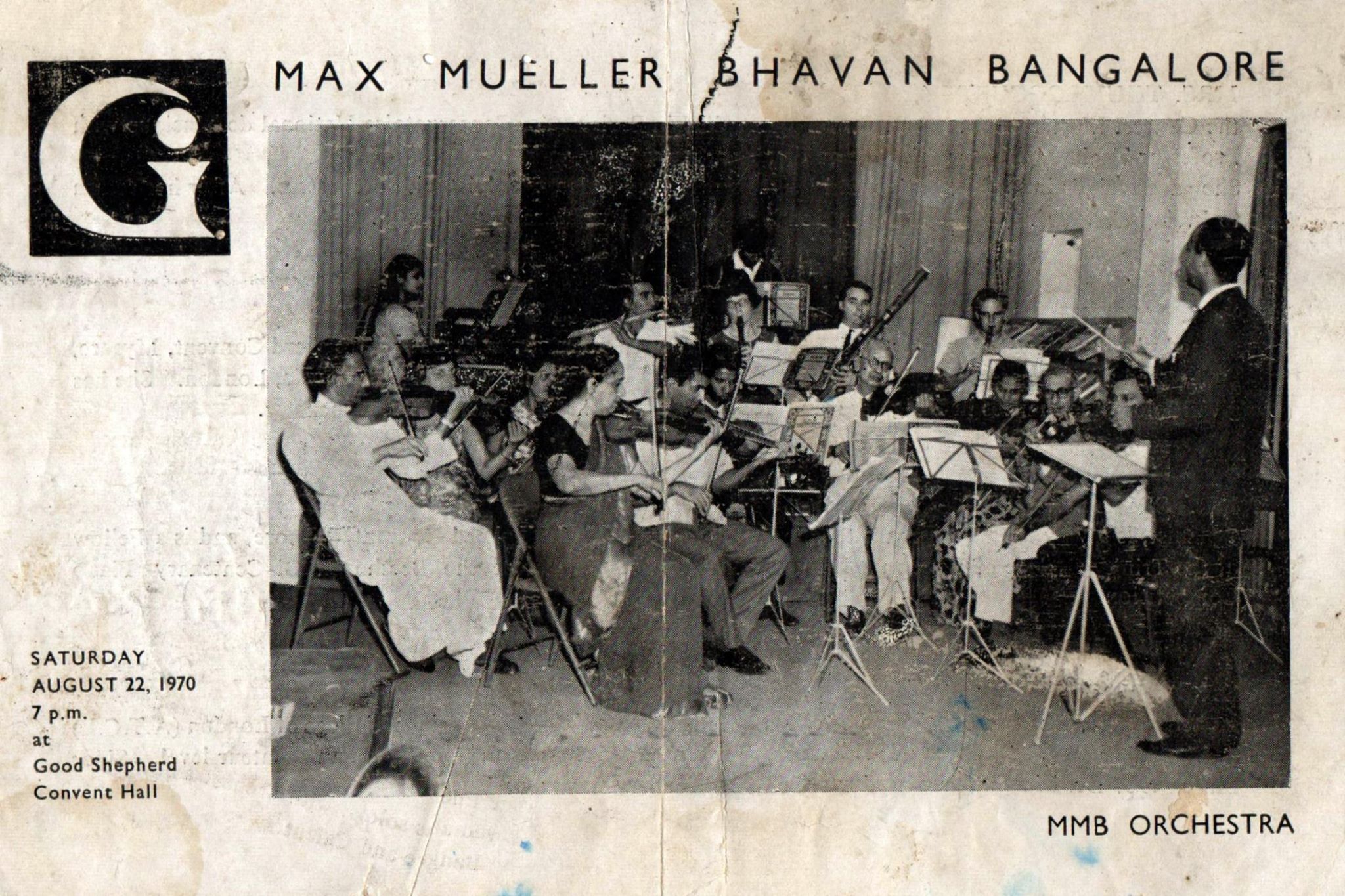

Her son talks of her active life as a performer in Bangalore. She played the ‘Kreuzer’ and ‘Spring’ sonatas with a visiting pianist from Poland and was the leader of the Max Mueller Bhavan Orchestra in the ‘60s and ‘70s. She ‘did what she could’ for her art, from the place where circumstances had put her. She taught Ravi the violin, and was “a very patient and very strong teacher, as much as she was a very caring mother. She emphasised the need to master playing techniques. There had to be at least an hour of scales every day. She would go through pieces phrase by phrase, examining every nuance.” In short, she taught the way she had learnt, and there were always surprises in store too. “I was very taken by Sibelius’ Violin Concerto. She asked me to get the score, and sight-read it to perfection. Until two years before she passed away” (in 2000) “she would play every day, not even neglecting scales, double stops, thirds, sixths…” It was a labour of love that neither time nor pressing domestic responsibilities could dim. She turned her keen intellect in other directions too, becoming an excellent chess player.

It is tempting to indulge in some “what ifs”: had she been born in a later age, would her blazing talent have had more outlets, and longer recognition? Today, when so many young Indian musicians in the field of Western classical music are finding it possible to find opportunities to perform across the country as well as Europe, to an increasingly aware audience, would she have been able to continue gathering the accolades that marked her early career? Ultimately, however, such speculations serve no more purpose than asking “If Mozart had lived longer, what greater riches would he have given the world?” Philomena Thumboochetty lived for her music, not for the fame it brought her. If her music held her audience in thrall, her life is a lesson for every musician.

Ravi Thumboochetty, who points out that his family sponsors two concerts annually in Philomena’s memory, has a vision: to carry forward the legacy she bequeathed him. He plans to open an academy of music in memory of “an extraordinary person and an extraordinary mother”.

(Sources for material and for quoting Philomena Thumboochetty are: The Indian Fiddler Queen. A Short Sketch of Philomena Thumboochetty, published by Dr K N Kesari at The Lodhra Press, Madras and The Singer and the Song: Conversations With Women Musicians by C.S. Lakshmi, published by kali for women. Ravi Thumboochetty was interviewed by the author)