PARSIFAL – PIERRE AUDI’S FORMIDABLE PRODUCTION AT DUTCH NATIONAL OPERA

Elucidating Wagner’s Rich Myth of Transformation

INTRODUCTION

It is hard to visit a performance of Parsifal without interpretative clutter getting in the way. It is not drawn primarily from a Christian source, despite being linked to Christian references. Nor is it a “sacred drama”, for Wagner had far more serious intentions than the simple-minded idea that he was simply deifying sensual renunciation in quest of spiritual truth. His search for original source materials for his operas led him to seek far and wide, grappling with ideas drawn from histories and mythologies far beyond his own native land. He even engaged with Buddhism, and nearly wrote a Buddhist themed opera Die Sieger (The Victors), but that did not advance beyond a brief prose draft.

Parsifal is Wagner’s last major operatic statement, weaving many themes and narratives into a flow of inventive dramaturgy, strangely austere but nevertheless rich in meaning. Seeing the revival of the 2012 production by Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam at the end of 2016, I was most struck by the sheer beauty of the composer’s final operatic score, with its rich blending of so many themes of human frailty, mortality, redemption and transcendence in a lucid and intelligent production by Pierre Audi.

DESIGN

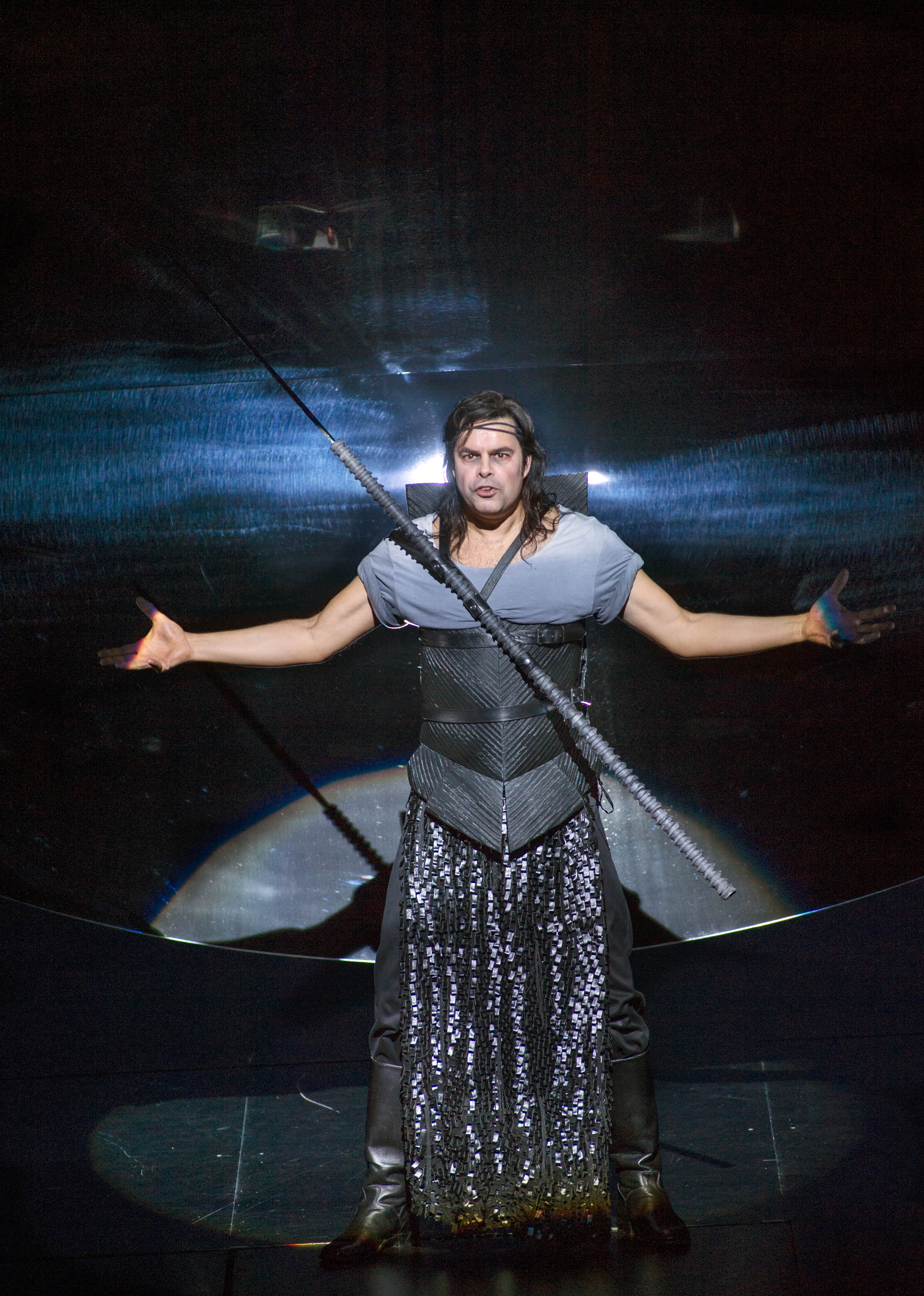

The set design by Anish Kapoor partly incorporated a gigantic concave mirror suspended by near invisible steel wires above the stage. This allowed director Pierre Audi to access the floor of the space clear of set artifacts, so that action could move freely. The presence of the huge mirror in some of the scenes was as much a reflective surface as also one that made available a meditative reflection on the deeper themes in the drama, graphically intensifying the figures of the actors moving before it in striking ways, both distorting and beautifying the amplified visual forms in a chaos of colour and form.

LONG SEQUENCES: A SUPREMELY DISTILLED READING

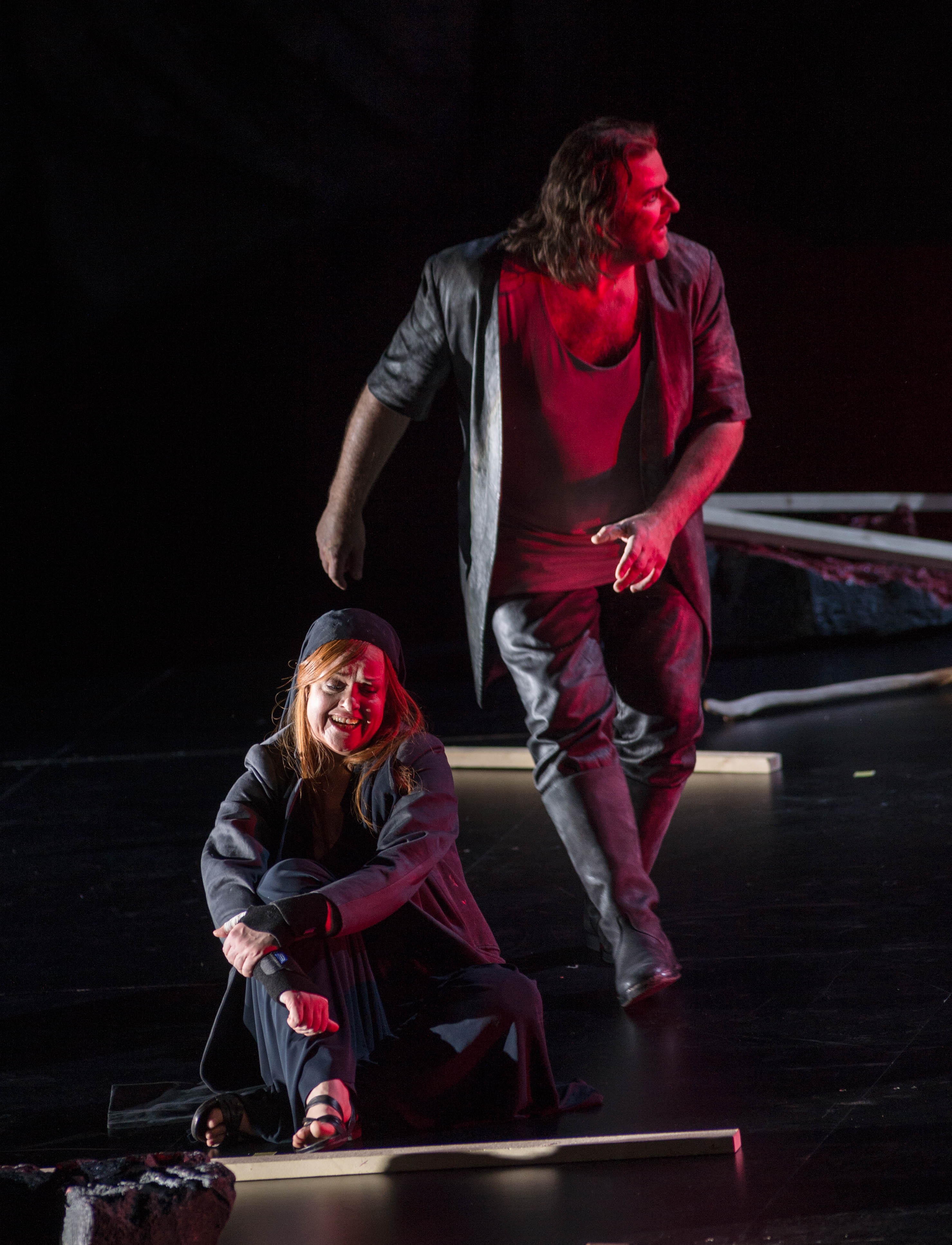

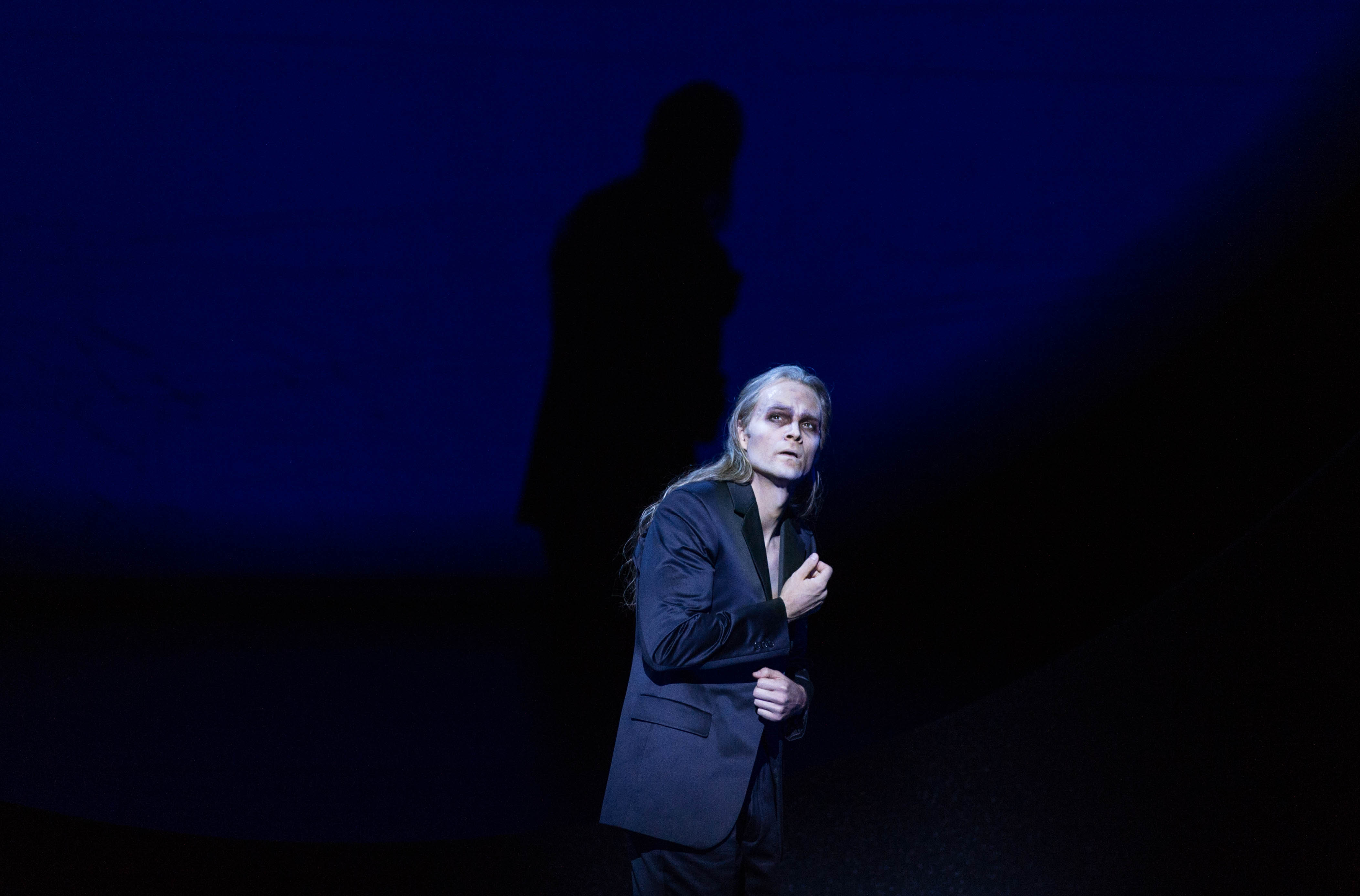

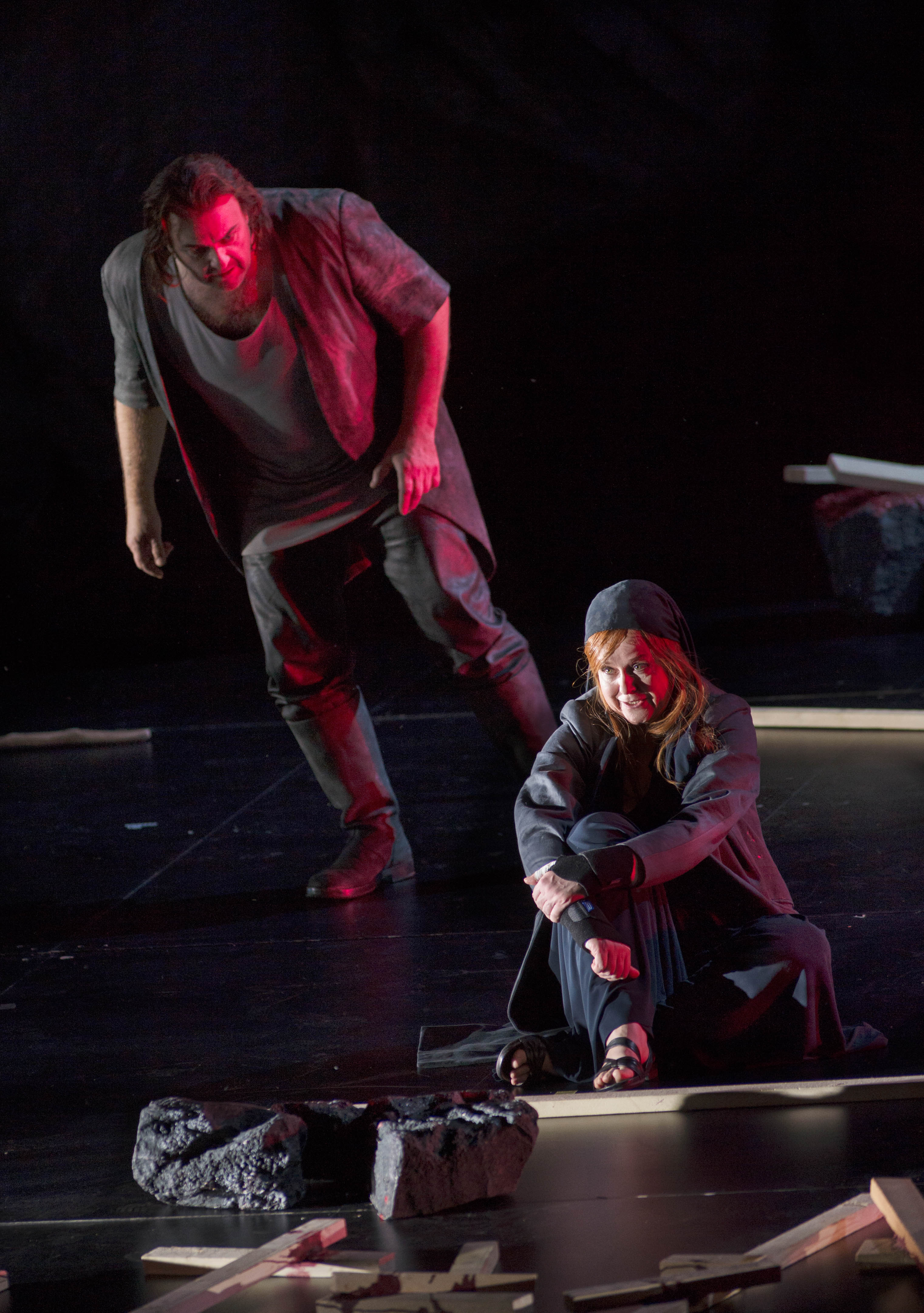

Parsifal is a gigantic work, an opera spinning out its three Acts over four hours. How does one approach a work of such provenance, with its enormous tracts of dialogue? Perhaps mindful of the interpretive hysteria that surrounds Parsifal’s identity, Pierre Audi chose simply to concentrate on elucidating some of the deepest levels of emotional surface, as in the unforgettable scene between Kundry and Parsifal, a tension whose resolution also makes possible the redemption of the entire kingdom of the Grail. Audi energised these long stretches of dialogues on an almost bare stage, marshalling the tested resources of a minimalist presentation, shorn of illustration. The exchanges with Kundry during which Parsifal peers through the mists of time to learn about his mother and his origins are some of the most deeply felt strophes in the opera, and an essential part of his personal journey. Even though Parsifal shot down a bird in flight in Act One with his cross-bow, his intentionality never harbours violence, and retains throughout a touching harmlessness of character and bearing. This innocent quality, untainted by the ravages of an upbringing that is normally the preserve of warriors and noblemen, makes it possible for him to eventually claim the power of a healer, and release Amfortas from his suffering. The tenor Christopher Ventris carried these scenes with enormous integrity, negotiating a rich and demanding score with authority and a sense of the title character’s inner resources. Parsifal’s journey from the innocent Fool to an enlightened Savant, in the body and song of Ventris, becomes a journey borne with forbearance, revelation and courage.

The “wound”, a ubiquitous reference point in Parsifal, is the dark centre of so much of the action, and a source of the suffering borne not just by Amfortas but also by his subjects. To that extent, this narrative oddly connects us with the Oedipus myth. In the Greek story the wound is borne by all of Thebes’ citizens, a land and its citizens accursed by an unknown plague, whose origins, we learn later, stem from Oedipus’s incestuous relationship with his mother, something Oedipus himself is unaware of. Self-knowledge, when it comes, is cathartic but devastating, destroying Oedipus, as he blinds himself brutally and stumbles away from his kingdom into exile. Parsifal however is no such tragedy; essentially transformative in its action, its revelation leads the character of Parsifal to a transcendent wakening. The Parsifal myth lies beyond Greek tragedy, and its many other strands of narrative come into play to bring about the transfiguration of a hugely interesting character, who is entirely believable and credible in his core of integrity.

Photos by Ruth Walz. Courtesy Nationale Opera & Ballet

CHRISTIAN AND CELTIC REFERENCES

Though commentators have suggested that Amfortas’s bleeding wound is analogous to the wound of Christ on the Cross, a close reading of the text shows that this link is only ancillary. The Parsifal story really originates in a Celtic myth of an infertile ruler, thereby inflicting his inadequacy on his subjects who are also thus afflicted and share Amfortas’s suffering. While Wagner does refer to the wound in Christian terms and to the ‘Redeemer’, his real interest is in Parsifal’s spiritual journey and the redemption of Amfortas and his subjects. The Christian references therefore are allusive and arguably rather glossed over. It is a sort of ambiguity that makes the narrative line less obvious and direct, leaving spaces for learning and reflection, yielding many facets of meaning.

However, allusions can be enriching, and whilst Wagner’s libretto sometimes moves through suggestion and ambiguity, the Christian elements that it is imbued with do offer a curious counterpoint to the main themes. So what of these elements? Mike Ashman, in his perceptive study of the opera writes: “Other elements in Wagner’s text show how Christian imagery is used but not merely imitated. The composer did indeed visit a Catholic priest in Munich to check on details of the liturgy and the Mass but no words of ritual in his Act One Grail scene are taken directly from that (or indeed any other) liturgy. The ‘great Communion scene’ which British writers at the turn of the century were so fond of praising – even fasting and praying before attending performances! – is a figment of their imaginations. The ‘baptism’ of Parsifal and Kundry, and the anointing of Parsifal in Act Three, use the elements of oil and water present in initiation ceremonies since recorded time. The story which Kundry confesses in Act Two – “I saw Him . . . Him . . . and laughed” – is an ingenious mixture of the legend of the Wandering Jew (who mocked Christ on the way to Calvary) and the many moments in Eastern folklore when characters only come to discover true compassion after showing contempt for the suffering. The deliberately vague geographical setting ‘landscape in the character of the northern mountains of Gothic Spain’ recalls medieval holy wars, specifically the 13th-century crusade against the Albigensian ‘heretics’ in the Pyrenees, but the challenge Klingsor presents to the Grail knights is more psychological than religious . . . ”

The major subplot in Parsifal is the fascinating portrayal of the unusual female archetype of Kundry, part messenger, part seductress, and part storyteller. Sung by Petra Lang, her vast role encompasses the remarkable journey from lust to loss and acceptance. Her importance in the emerging drama had been entirely missed by the Knights of the Grail, who treated her coarsely. She is disruptive, hard to pin down or control, the psychological forces driving her somewhat a mystery. Yet her path strangely complements Parsifal’s own journey from a rejection of sensuality to wisdom. Most importantly she brings to Parsifal the knowledge of his mother and father, of his childhood, a knowledge that he needs to embrace in order to understand himself, and seize his destiny. A commentator Carolyn Abbate writes: “The Kundry-Parsifal scene is remarkable not for any real interaction between the characters but for Parsifal’s metamorphosis. Although Kundry is hardly negligible in this process, she is strangely neutral. Her role is to impart knowledge, thereby enabling Parsifal to achieve a transformation she could not foresee, into a mythic hero she cannot control.”

BUDDHIST LEANINGS

It is tempting to see a strong influence of Buddhism in Parsifal. But there are some striking differences too. What originally impelled the young Sakyan prince Gautam to asceticism was not a rejection of the sensual world in itself, but his relentless search for an immutable state of grace, free from suffering. This was the primary motive of the movement towards Enlightenment. That it involved, ultimately, a rejection of sensual experience as a temporary and dubious gain, is a natural consequence of his primary search for a transcendent state free of the causal processes that bring about suffering. In Wagner’s dramaturgy however, the rejection of sensual experience is very much in the foreground, as in the rejection of the advances of the Flower Maidens and in the rejection of Kundry’s amorous demands, which are all too human. But it is a psychological rejection, not a religious one. Once Wagner had charted Parsifal’s transformation from innocent Fool to Wise Sage, he felt he had achieved his objective and could walk away from the pseudo-Buddhist opera Die Sieger that he had once thought of writing.

THE MUSIC

An extraordinary blend of recurring themes, all closely linked motivically, as well as ambiguities in harmony and several references to Wagner’s previous works show what a rich amalgam of musical ideas informed his musical processes. There are telling references to Lohengrin, The Mastersingers, Tristan and the Ring Cycle – as it were, a conscious coalescing of themes by a seasoned composer creating a unified harmonic field filled with mythic resonances that had preoccupied and inspired him his whole life. The dramaturgical achievement of tying the music to the narrative drama is immense, and it isn’t terribly perceptive to disparage the theatrical power of the work and to claim – as some notable commentators do – that all of the drama is in the music. That would discount the incredible skill needed to blend so many strands of textual narrative together and to underpin these in a web of musical grundenmotives that are in a perennial state of iteration and transformation. The text of this work was itself an enormous undertaking, and fashioned by a superlative story-teller.

From the moment the gentle and searching unison monody, bereft of any obvious metrical pattern, launches the luminous Overture, the music was deftly and powerfully directed by Marc Albrecht, chief conductor of the Dutch National Opera, who is equally at home in traditional operatic repertoire as in contemporary music. There was not one faltering beat or bar, and the baton fell with incredible grace and power on every musical surface, with the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra lighting up harmonies of lustrous resonance. Tempi were perfectly judged, elucidating emotional energy in a landmark performance, that one could cherish and for long summon to memory.

THE GENIUS OF PIERRE AUDI

Pierre Audi has had a brilliant tenure at Dutch National Opera (formerly De Nederlandse Opera) as Intendant for well nigh 30 years and left an indelible mark on the company. He has had many groundbreaking productions to his credit, including the entire Ring Cycle, and has been responsible for commissioning and mentoring a plethora of modern composers, and for consistently producing work of vision. He came to Amsterdam after a brief period with London’s hugely successful Almeida Theatre, which he also founded. He leaves his post in Amsterdam in 2018 for other challenges in the operatic stratosphere. It is hard to imagine who could succeed him.

Audi’s deft and experienced hand was evident throughout the performance of Parsifal – in the delineation of the dramatic line, constantly in touch with emotion, in the inspired choice of a brilliant visual artist to design the set, but above all in the meticulous attention he paid to the qualities embedded in the script and the score. His reading allowed the character of Parsifal, in all its complexity and beauty, to come through lucidly, shorn of any hint of pretension, speaking at the most elemental level of feeling. If this, Wagner’s last opera, is overwhelming, the production did it overwhelming justice. Audi’s great hallmark as a director is his unerring ability to energise a long drawn out dramatic process with tension and sensitivity, without any disruptive clutter and without reliance on decorative surface gesture. His dramatic approach in Parsifal was spare, minimal, elucidating the expressive intentions of a composer at the height of his powers. At a time when sensate art seems to be all the rage, this was an eloquent statement of ideational art at its most expressive and intense.

Synopsis of PARSIFAL

By SAMUEL MILEA

ACT I

The experienced knight, Gurnemanz, rests with his two esquires in a forest near the castle of the brotherhood of the Holy Grail. As they recite their daily morning prayers, other knights collect water from a nearby forest lake. It is in this water that Amfortas, their King, will bathe his incurable wound. At this moment Kundry enters, an ageless woman and messenger of the Grail, thrusting a small crystal flask into the hands of Gurnemanz. “Balsam – for the King!” she exclaims curtly, intending to ward off any thanks. Gurnemanz, considering the balsam, reflects on a prophecy that speaks of the King’s salvation only by a “pure fool, enlightened by compassion.” He proceeds to speak of Klingsor, a sorcerer with intent to destroy the brotherhood, and tells the story of Amfortas’s wound: the spear which pierced Christ’s body on the cross and the Holy Grail, the cup drank from at the last supper, were handed into the care of Titurel, the father of Amfortas. It was he who assembled the brotherhood of knights to guard the relics. The young Klingsor, wishing to join the brotherhood, castrated himself in his attempt to clear his mind of sinful thoughts, but was rejected. In vengeance, he built a castle across the mountains, complete with a magic garden laden with seductive women designed to entrap the knights. Amfortas, seeking to defeat Klingsor, was stabbed by the holy spear which was taken from and used upon him amidst the heat of battle, after himself being seduced by a fair maiden. Gurnemanz explains that Amfortas’s wounds can only be healed by the enlightened fool that the prophecy has spoken of. A moment later a wounded swan, one of the sacred birds of the Grail brotherhood, flutters overhead and falls dead. Two knights bring forth a young man who is boasting about his archery skills. He accused of murdering the bird. He feels ashamed, and when questioned about his parentage, he knows little, recalling that his mother’s name is Herzeleide, or Heart’s Sorrow. He attempts to recall the many pet names she gave him, but even this is in vain. Kundry speaks of the youth’s personal history: his father perished in battle and his mother, now dead, raised him in a forest. Gurnemanz, with the prophecy still in the forefront of his mind draws early conclusions and leads the youth to the castle.

Upon returning to the castle the knights assemble and Titurel requests that Amfortas reveal the Grail to give strength to the brotherhood. This is to no avail, as Amfortas claims that the sight of the relic maximises his pain. Despite this, Titurel orders the esquires to proceed and the ethereal light of the Grail sets the castle halls aglow. With both a blissful ignorance and a growing curiosity, the youth watches on.

ACT II

Klingsor summons Kundry to his castle, who, whilst under his spell, is required to seduce the fool. With spear at hand, Klingsor intends to kill the young man, knowing that he is the saviour of the Grail brotherhood.

The youth, still nameless, enters the magic garden and seeks to mingle with the beautiful women. They crowd around, all competing for his attention by making alluring gestures and singing beautiful melodies. The passion culminates with Kundry, now transformed into a beautiful young woman, appearing. She addresses him by his name – Parsifal. Kundry reveals more about his mysterious past and eventually kisses him. It is this which has sealed the fate of many a knight, but in the youth, it inspires a sudden change. The mind of the “fool” has been transformed from one of unconsciousness to consciousness. Aware that her kiss has had no effect on Parsifal, she curses him to wander endlessly in search of the Grail brotherhood. In a final attempt, Kundry calls upon Klingsor for aid. The sorcerer appears and hurls the spear full at Parsifal, but it rises in flight and remains suspended over his head, as if he is protected by some other-worldly force.

ACT III

Now an aged man, Gurnemanz finds an exhausted Kundry in the wood near the Grail’s castle. Parsifal approaches, clad in blackened armour, and sits innocently nearby, laying the reclaimed spear at his side. To Gurnemanz, the initially unidentifiable Parsifal is an intruder on Holy ground, but as Parsifal removes his mask his identity becomes apparent. Gurnemanz exclaims that he has arrived at the right time, as Amfortas, longing for death, has repeatedly refused to uncover the grail. Titurel is dead and the brotherhood is suffering. Parsifal is blessed by the old knight and is sworn King. His first task to baptise Kundry. As he stands in the forest he notices his surroundings, captivated by its beauty. The three make way to the castle as the distant tolling of bells can be heard, signifying the death of Titurel.

In the castle, the Knights behold the Grail. “Slay me!” cries Amfortas. “Take up your weapons! Bury your sword blades deep – deep in me, to the hilts! Kill me, and so kill the pain the tortures me!” At this moment Parsifal enters and touches the wound with the point of the spear. It is immediately healed. The knights pay homage to the new King and he blesses them. The prophecy has been fulfilled and calm and order has been restored to the brotherhood.