ODE TO BEETHOVEN: PART II

A tribute on Beethoven’s 250th birth anniversary

“Whoever gets to know and understand my music, will be freed from all the misery the world has to offer.” – Ludwig van Beethoven

What caused Beethoven’s deafness? Unfortunately, his autopsy report was destroyed. Notes made by Dr. Johann Wagner, the pathologist, survived, but they are hardly conclusive, leading to endless speculation over the years. The most likely answer is lead poisoning. A young musician called Ferdinand Hiller snipped off a lock of Beethoven’s hair as a keepsake (a common practice those days), and in recent times, these hairs have been analyzed with modern technology: imaging, DNA, chemical, forensic and toxicology testing. The only significant finding was an abnormally elevated lead level, potentially indicating chronic lead poisoning, which could have caused Beethoven’s deafness, though it does not explain his other multiple health ailments. Beethoven loved wine, and studies suggest he probably drank it from a goblet containing lead. Moreover, the wine in his day was often laced with lead as a sweetener.

To a musician, no malady was as diabolical as deafness. As noted in Part I, in June 1801, he wrote to Dr. Franz Wegeler, his childhood friend:

“For almost two years I have ceased to attend any social functions, just because I find it impossible to say to people: I am deaf. If I had any other profession, I might be able to cope with my infirmity; but in my profession it is a terrible handicap. And if my enemies, of whom I have a fair number, were to hear about it, what would they say?….

In a letter to another close friend, the violinist Karl Amenda, Beethoven wrote:

“In my present condition I must draw away from everything and my best years will rapidly pass away without my being able to achieve all that my talent and my strength have commanded me to do — sad resignation, in which I am forced to take refuge. Needless to say, I am resolved to overcome all of this, but how can that be done?”

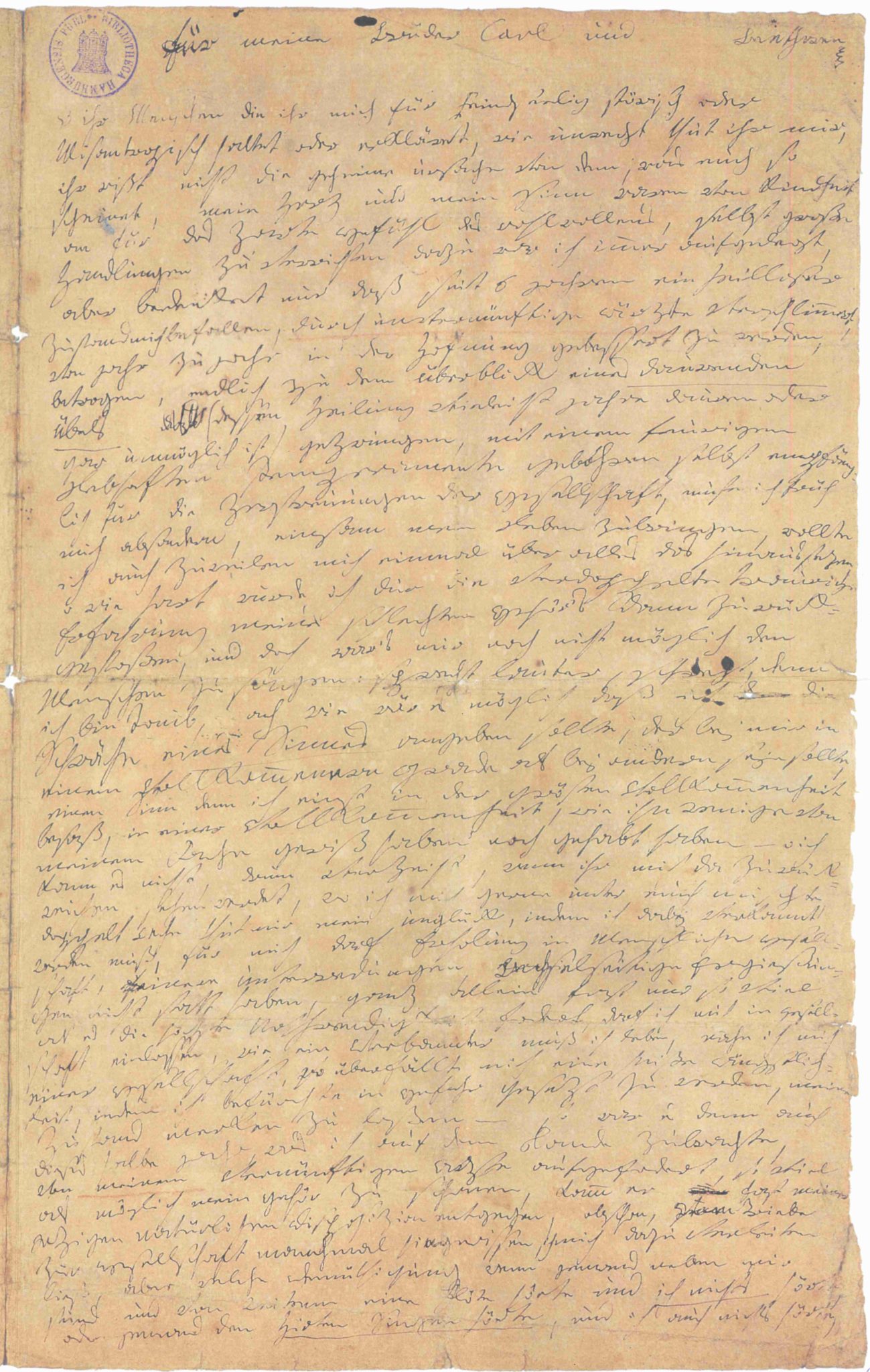

The Heiligenstadt Testament

In April 1802, Beethoven rented a farmhouse in Heiligenstadt, a secluded resort in the hills northwest of Vienna. His doctor had recommended it not only for its mineral springs, believed to have curative properties, but also for its tranquillity which, the doctor felt, would be therapeutic for Beethoven. His piano student Ferdinand Ries often visited him there. They often went for long walks in the lush Austrian countryside.

One day, without thinking, Ries commented on the lively music that a shepherd was playing on his flute at a distance. Beethoven strained to hear it for a full thirty minutes (they were walking towards the music) but heard nothing. “He became extremely quiet and morose,” Ries said.

It was the bleakest day in Beethoven’s life, as he wrestled with the horrible realization that his deafness had reached an advanced stage and was probably incurable. Ludwig, what is the use of living anymore, his mind demanded as it shot out suicidal thoughts. Then his stubborn willpower countered: Ludwig, your art is everything, and you are its master. Surely even in the most challenging situation, can’t you — as you yourself have said before, — seize Fate by the throat, and not allow it to crush you?

All summer long, his inner battle raged. Autumn came, the leaves changed colour and dropped. On October 6, Beethoven wrote an extremely lengthy document addressed to his brothers and to be delivered to them should they outlive him, but it fundamentally was a confessional letter from himself to himself. At the same time it also was a statement to the world at large and to posterity, for its first words are: O ihr Menschen (O you people). His music compositions were laced with tension and resolution, and something similar is reflected in this missive: his willpower winning his mental battle by successfully arguing why suicide was not an option. This document, now called The Heiligenstadt Testament, which surfaced only after Beethoven’s death, is unparalleled in the history of music. In one of the most heartfelt outpourings from an artist, Beethoven describes his suffering, wrestling with his inner demons, and his long struggle, to regain his wrecked confidence and continue as a composer despite the loneliness that would haunt him for the rest of his life. Here is an excerpt:

“What a humiliation for me when someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing. Such incidents drove me close to despair, a little more of that and I would have ended my life — it was only my art that held me back. Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I produced all the works that I felt the urge to compose.”

Never again was Beethoven going to reveal his inner feelings in so heartrending a manner. This document was never sent to his brothers. It was meant to come to light after his passing, as a posthumous revelation. But Beethoven was going to find light amid the darkness and compose some of his greatest works as his deafness progressed, culminating in another unmatched achievement: composing a symphony, his ninth, when he was totally deaf, rising from the deepest despondency to an unimaginable summit. The climax of that symphony (An Die Freude, or Ode to Joy, in the fourth movement) has cemented Beethoven’s legacy in that it is his best known composition around the world. Even people who have never heard any of his other music know this one. “Beethoven!” they exclaim, when they hear it.

In the postscript to the Heilgenstadt Testament, Beethoven presciently solidifies his resolve. Note his use of the word “joy.” Here is the text of the postscript:

“As the leaves of autumn fall and are withered — that hope has faded for me. I leave here in almost the same condition in which I came; even that buoyant courage that often inspired me in the beautiful days of summer has vanished. O Providence! Grant me but one day of pure joy! It is so long that the inner echo of real joy has gone from me — Oh when — Oh when, Almighty God — shall I hear and feel it again in the temple of Nature and humanity? — Never? —No — Oh, that would be too hard.”

Beethoven’s magnum opus, The Ninth Symphony

Beethoven never wrote a bad symphony; he was incapable of it. All music aficionados have their favourite Beethoven symphony. But many consider the Ninth Symphony (also referred to as “Chorale” or “Choral Symphony”) as the pinnacle of Beethoven’s achievement, and often that is for the music alone. When put it into the context of his life — his total loss of hearing lost when he composed it — it becomes hypnotic, dazzling. George Eliot commented that Beethoven’s greatest works were composed in “the roar which lies on the other side of silence.”

A hallmark of Beethoven’s work is tension and resolution. His biographer Edmund Morris wrote: “Whether it was major against minor over the course of an entire symphony, or the masculine-feminine contrast of craggy and seductive themes in a single movement, or the structural split, like that of xylem and phloem, in the cross section of his tiniest motifs, all was tension, everything had to be resolved.”

As Beethoven evolved as a composer, he became noted for the most unconventional beginnings for his symphonies and sonatas. But, wrote Morris, specifically referring to Piano Sonatas Op 31: Numbers 1, 2, and 3:

“…these beginnings were mere tokens of the shocks Beethoven had in store for any pianist capable of negotiating his formidable technical demands: unpredictable silences, off-beat cadences, ricochet repeated notes, gorgeous melodies mysteriously interrupted by drum taps or reverse vamps, and, weirdest of all, two long stretches of recitative in the D-minor sonata (Op. 31; No: 2) played pianissimo with both pedals down in imitation of a voice echoing from the depths of a vault.”

In The Ninth, Beethoven made the structure of a classical symphony bend to his will to express his profound philosophical theme: the unity of mankind and our place in the universe. The Ninth begins in an unusual way, never before heard in any composer’s symphony. There is no motif, no shattering opening gesture. The opening develops over 16 measures from absolute silence to a peak, during which Beethoven introduces his music gradually. Only after the 16thmeasure does the music erupt with a volcanic force. Many have commented on its Biblical parallels, an alternate opening of the Book of Genesis: In the beginning, there was Silence. And the Lord said, “Let there be sound,” — and music was born.

But, keeping in mind John Suchet’s argument that Beethoven’s life situation is reflected in all of his music, here is another interpretation. The artist, despite his deafness and by the sheer dint of his willpower and perseverance, milks out music from silence. Whatever their interpretation, everybody agreed they were hearing a kind of music not encountered earlier.

The second movement is a Scherzo, the Italian musical term for “joking or playful.” Though it opens in a serious way, Beethoven quickly moves to a playful tone. The remarkable feature is that the timpani, hitherto used only as an accompanying instrument, is given its own solo slot. Today timpani solos are accepted, but it started with Beethoven’s Ninth.

The third movement is a slow adagio. It can be melancholy arising from the vicissitudes of life, or a prayer, or both. All of these movements lead up to the pinnacle, the fourth movement.

The fourth movement creates a feeling of brotherhood and humanity, the ultimate message of the symphony. From his youth Beethoven, so taken by Friedrich Schiller’s poem An die Freude (Ode to Joy) had always wanted to set it to music. He finally did so as the culmination of The Ninth. This was as radical as one could get in the classical music of his day whose unshakeable rule was: Chorus was Chorus and Orchestra was Orchestra, and never the twain could meet. Beethoven disregarded it with impunity by including Schiller’s poem as a chorus in the fourth movement of an orchestral work. But although he threw out structure and form, he retained the theme, keeping only those verses of An die Freudethat fitted into the vision that the symphony conveyed. For instance, he discarded many of Schiller’s verses that sounded like they were from a drinking song.

Beethoven introduces Ode to Joy with a bass soloist’s intonation: O Freunde, nicht diese Töne! Sondern laßt uns angenehmere anstimmen, und freudenvollere. (O friends, not these sounds! Rather, let us intone more cheerful and joyful ones.) This is not part of Schiller’s poem. This is Beethoven’s direct communication with his audience. He is also instructing the soloists and the chorus to produce not just a symphony finale but also a rousing vocal celebration of joy and universal brotherhood. With this single sentence, he sets aside all the previous three movements with their resonances of tragedy, bereavement, and discord, albeit mixed with moments that are playful and which uplift. This is followed by selections from Schiller’s poem, the opening lyrics to which are:

Freude, schöner Götterfunken

Tochter aus Elysium,

Wir betreten feuertrunken,

Himmlische, dein Heiligtum!

Deine Zauber binden wieder

Was die Mode streng geteilt;

Alle Menschen werden Brüder,

Wo dein sanfter Flügel weilt.

Joy! Bright spark of divinity,

Daughter of Elysium,

We invade all fire-drunken

Heavenly One, thy sacred shrine.

Thy enchantment binds again

All that custom rudely divided,

Mankind unites, as brothers,

Where thy gentle wings abides.

In the video below, conductor Marin Alsop shows how Beethoven, at the start of the fourth movement, introduces key snippets from the three previous movements of the symphony as reminders, only to have the basses and cellos interrupt and end them. This prepares us for the bass soloist who later intones “Not these sounds.” But the past is connected to the future. Without remembering your past the future cannot be placed in context; you cannot understand what “Not these sounds” means.

Conductor Marin Alsop’s commentary on the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony

To replace what came before, Beethoven presents his ultimate solution. Maynard Solomon, in his biography Beethoven, writes: “…the ‘Ode to Joy’ preaches ‘the kingdom of God on earth, established by the brotherhood of man, in reason and in joy.’ In the last analysis, Beethoven’s private quest and his ideological thrust are identical: a search for an ideal, extended communal family to assuage the inevitability of personal loss, to maintain and to magnify the sanctified memory of his — and everyone’s — personal Eden.”

Renowned conductor Leonard Bernstein said Beethoven’s music, and Ode to Joy and The Ninth Symphony in particular, “…is not only infinitely durable but perhaps the closest music has ever come to universality….No composer has ever lived who speaks so directly to so many people….to all classes, nationalities, racial backgrounds. This music speaks a universality of thought, of human brotherhood, of freedom, and love.” He briefly expounds on these thoughts in the video below:

Leonard Bernstein’s commentary on Beethoven, Ode to Joy, and The Ninth Symphony

Many hum the base melody of Ode to Joy, and think it is something a simpleton could have composed, and wonder what the fuss is all about. Such people are unaware that Ode to Joy is far more complex than the tune most of us hum.

Ode to Joy performed by The London Symphony Orchestra (Conductor: Sir Georg Solti) and The London Voices (Chorus Master: Terry Edwards)

The composition begins on a solemn note with cello and contrabass, and then turns lighter and sweeter when the viola and bassoon join. It blooms when the first and second violins enter. Then it turns majestic when the full orchestra plays, which includes flute, oboe, clarinet, cornet, contrabassoon, trombone and timpani, all leading to a resounding cadence, after which the bass soloist intones “Not these sounds,” preparing the audience for the chorus that will follow.

The Legacy of The Ninth Symphony

The Ninth Symphony marked a transition between two eras of music. It was a somersault from the Classical Period into the Romantic Period, where composers began breaking the rules of composition and exploring the use of large ensembles and orchestras, extreme emotion, and unconventional arrangements. And they drew their authority from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Musicians and music lovers alike would say “The Ninth” in hushed tones, and there was no need to explain further — they knew what was being referred to.

Brahms was so intimidated by The Ninth that it took him a full twenty-five years to compose his first symphony. And its ending has resonances with Beethoven’s Ninth. When this was pointed out to Brahms, he shot back, “Any jackass can see that!” adding that it was more in homage rather than plagiarism. Wagner’s career in music was shaped by The Ninth. In his autobiography Mein Leben, Wagner wrote that he was compelled by the “mystical influence of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony to plumb the deepest recesses of music.” Schumann was quoted as saying that listening to The Ninth was a transforming experience: “I am the blind man who is standing before the Strasbourg Cathedral, who hears its bells but cannot see the entrance.” Gustav Mahler credits The Ninth as enabling him to build his own complex symphonic structures, saying that the symphony as an art form “must have something cosmic in itself, must be inexhaustible, like the world and life.” Several other composers were influenced by The Ninth, including Anton Bruckner, Franz Liszt, Antonín Dvořák, Felix Mendelssohn, Hector Berlioz, César Franck, and Béla Bartók. The Ninth took on such a mythic status, says Beethoven biographer Lewis Lockwood (in Beethoven: The Music and the Life) that “it is not surprising that no major composer of symphonies after Beethoven down to the early twentieth century wrote no more than nine, as if this work had set up a virtually permanent standard.”

Bernstein spoke of how Ode to Joy, whose words (and vitally, its music) crosses boundaries of nationality, culture, race and personal beliefs. Events bear him out. Even in its composer’s day, the demand for equality in society was reflected in the writings of Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac, Nikolai Gogol, and Charles Dickens. Beethoven conveyed the same desire through music which has struck a chord in people’s hearts down the years.

Ode to Joy is regularly played during the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games. It (the music without the words) is the official anthem of the European Union. Japanese orchestras performed it during the country’s reconstruction after World War II and its recovery from the nuclear devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Chinese students hummed it as the battle tanks rolled towards them at Tiananmen Square. Chilean protestors used it in response to the oppression of Pinochet. The Germans sang it with gusto as they tore down the Berlin Wall, and Leonard Bernstein flew over to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic performing The Ninth, with musicians from East and West Germany playing together for the first time in decades symbolizing, through music, the long-sought unification of a divided Germany. For this occasion, Bernstein took a little artistic liberty: freude was replaced by freiheit. That is, Ode to Joy became Ode to Freedom.

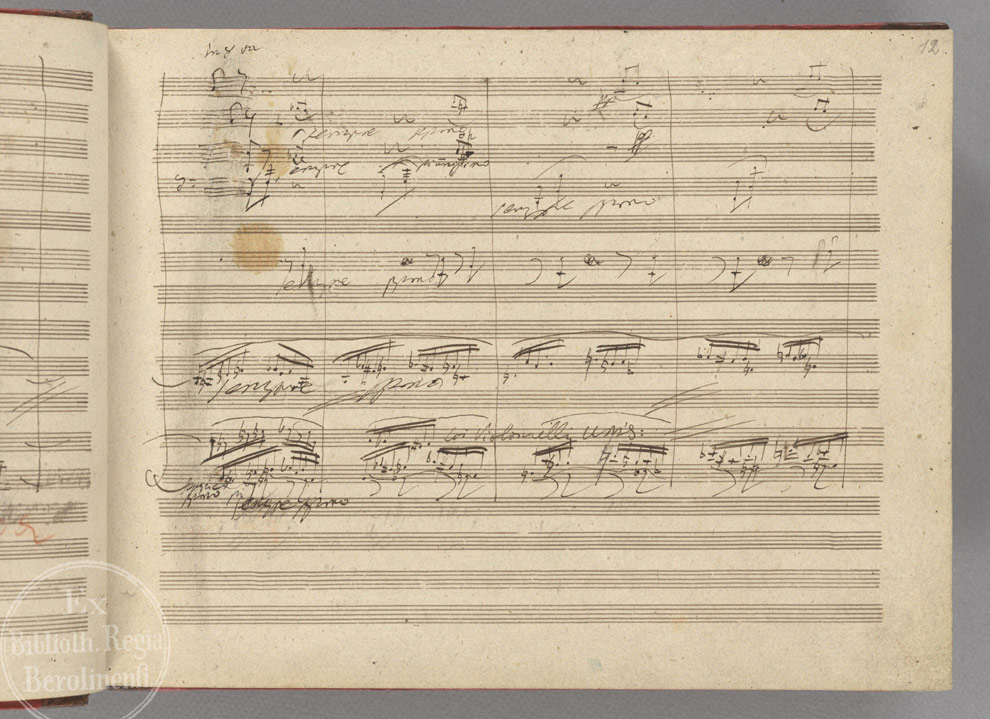

In 2001, Beethoven’s original, hand-written manuscript of the score, held by the Berlin State Library, was added to the Memory of the World Programme Heritage list established by the United Nations, becoming the first music score so designated.

These are just a few examples of the composition’s enduring, worldwide appeal. Music historian Harvey Sachs declared: “there is one inescapable fact”: the Ninth Symphony “belongs to each person who… attempts to listen to it attentively.” We may never agree about what it means, but, as with a total solar eclipse or other equivalent natural phenomena, we can encounter it with humility and wonder.

In keeping with this, it is not surprising that Ode to Joy is one of the favourite choices of orchestras that are doing virtual (online) concerts when the Covid-19 pandemic has rung down the curtain on worldwide events to celebrate Beethoven’s 250th birth anniversary.

Music in the Time of the Coronavirus | Ode to Joy – Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra

The legacy of The Ninth surfaces in unanticipated ways. When Philips and Sony decided that the sun had set on spool cassette tapes and started to collaborate on a new audio format to be called Compact Disc (CD), they argued over what size the discs should be. Philips pushed for a 11.5 cm diameter disc while Sony wanted 10 cm. Kees Immink, Philips’ chief engineer in charge of the project, consulted various experts, one of who insisted that a single disc ought to have the capacity to contain a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in its entirety. The duration of The Ninth ranges from about 65 to 74 minutes which requires a 12 cm diameter disc. And that is why CDs (and later, Digital Video Discs or DVDs) have been standardized to this size.

Coda

Earlier it was mentioned that Beethoven had a soft corner for his piano student Countess Giulietta Guicciardi, to whom he dedicated Moonlight. The budding romance was broken up by her father. Beethoven continued to be unlucky in love, and lived and died a bachelor. Immortal Beloved was a 1994 film about Beethoven, specifically exploring the roles that women played in his life. Historians of music have taken umbrage at the storyline, saying that the filmmakers played fast and loose with the factual details of Beethoven’s life. Amadeus, a biopic on Mozart, similarly took great liberties in dramatizing a feud between Mozart and a contemporary composer, Antonio Salieri. While the two were rivals, Salieri was not so eaten up with jealousy to murderously propel Mozart to an early death as the film implies. On the upside, Amadeus has dazzling period costumes and introduced Mozart’s music to a new generation hitherto not interested in classical music. Similarly, despite historical inaccuracies galore, Immortal Beloved also helped make audiences curious about the life and music of Beethoven.

An outstanding sequence from Immortal Beloved is the scene depicting the premiere of The Ninth Symphony on Friday, 7th May 1824 at the Theater am Kärntnertor, Vienna. It captures the atmosphere beautifully — the musicians played, and the audience watched, by candlelight. For its day, the orchestra was huge. Beethoven insisted in conducting but was persuaded to do so with a co-conductor, Michael Umlauf. There were only two rehearsals, and both were disasters. It was clear that Beethoven, totally deaf now, could not hear any of the instruments. Umlauf instructed the orchestra to follow him and not Beethoven on the premiere night, which they did. (Unlike what is shown in the film, Beethoven was onstage for the full symphony, not just the fourth movement, and he did not stand passively but actively conducted, though the orchestra followed Umlauf.)

As the music unfolded, it slowly dawned on audience that this was going to be a defining event in the annals of music. As the notes of the final chord subsided, the audience erupted in thunderous cheering: “Beethoven! Beethoven! Beethoven!” But Beethoven, several measures off, was still conducting — not the orchestra in front of him but the one playing in his head. Karolina Unger, the contralto soloist, stepped down from the choir and gently turned Beethoven around to face the audience. Many in the audience were overcome; they knew Beethoven was deaf but had little idea that his condition was so advanced. That simple gesture of a chorister turning the composer around sent an electric shock through the audience. The applause broke out again with triple the intensity; and now hats, handkerchiefs, scarves and walking sticks were waved in the air, so that Beethoven could “see” the applause even if he could not hear it.

The most poignant moment in Immortal Beloved occurs in this video sequence when we are given a brief glimpse into Beethoven’s deafness. His magnificent music swirls around him but he cannot discern a single note, and he is on stage hearing nothing but dead silence. The moment of his greatest triumph is also filled with indefinable anguish. And in that moment, we realize what the greater part of his life must have been like for him, and our hearts ache for him even as we now understand his greatness all the more, seeing what a steep obstacle he was able to surmount to offer the world his unique creations.

“Ode to Joy” scene from the film “Immortal Beloved.” Gary Oldman plays the adult Beethoven, and Leo Faulkner, the young Beethoven.

Equally powerful imagery follows: a flashback to Beethoven’s youth when he and his brothers were terrorized by their abusive, alcoholic father. The young Beethoven flees from his father’s wrath, running as fast as he can through the woods at night, and lies down in a pond. The moon and the stars are also reflected in the water of the pond. And then, as the choir sings the words of Ode to Joy the boy is transported in the blink of an eye from the water high into the night sky, receding farther and farther until he becomes the brightest star in the sky, and then merges with the Milky Way and our galaxy. This is a striking visual tribute to Beethoven’s music — it has become one with the cosmos, it is now music for eternity.

While we stand in awe of Beethoven’s body of work, as we ought to, it is also important to realize that in his lifetime he was all too human although god-like statues and monuments to him have been erected. He largely shunned royal and aristocratic patronage, preferring to rent his lodgings and compose his music in peace and quiet the way he wanted and not the way others wanted. He was sometimes evicted by his landlords when he couldn’t come up with the rent. He had as many enemies as he had friends. He was often heavily in debt. He was unable to find a woman who would be his wife and life companion; he had no family life. He was at loggerheads with his sister-in-law — including a protracted court battle — over custody of her son and his nephew, Karl.

He was a petulant man with a short temper, no doubt exacerbated by his health issues, which upset his friends and alienated his business associates. But he could also overwhelm people with overdoses of kindness and unbelievable generosity. The political environment he worked in was fraught with uncertainty: Austria was in perpetual turmoil because of political tensions and wars with archrival France. Superimposed on all of this was his lifelong struggle with deafness.

The American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote:

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;

Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

In other words, as John Suchet wrote, Beethoven’s music is his autobiography, for his life and his music are entwined: point and counterpoint. The ways in which he did not allow the impediments in his life to interfere with his art holds as many lessons for us as his music. Beethoven has imprinted his footprints on the sands of time, and his music is music for the ages.