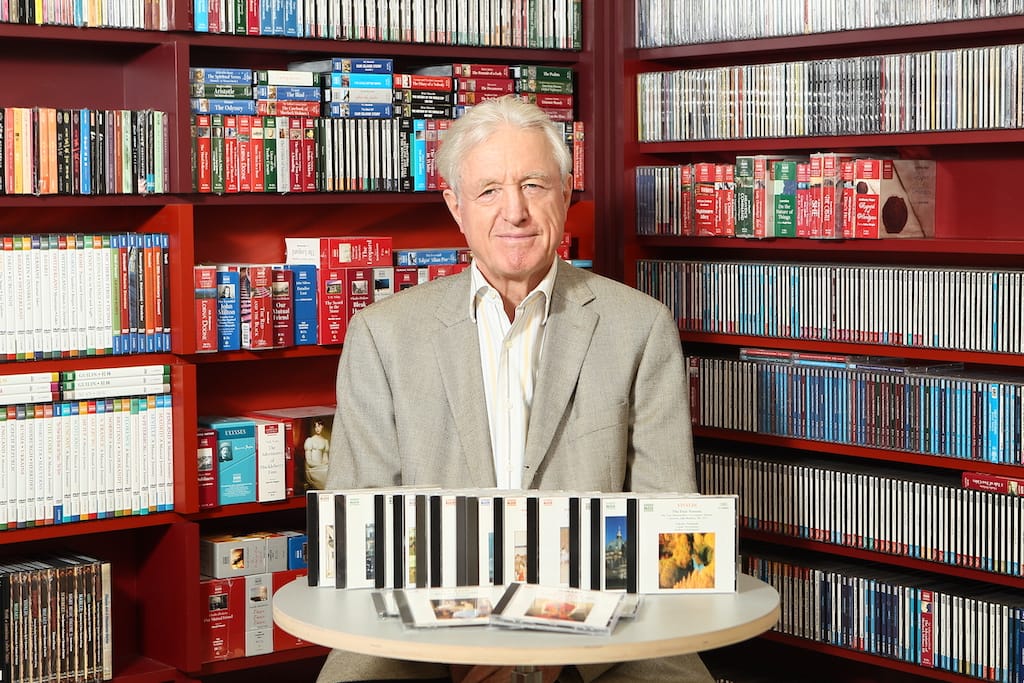

Naxos Records and Beyond: Klaus Heymann’s Musical Odyssey

In the world of classical music, few figures have had as profound an impact as Klaus Heymann. His journey from a young, adventurous entrepreneur to the visionary founder of Naxos Records is a tale of innovation, resilience, and an unwavering commitment to classical music. With a career spanning decades, he has witnessed the transformation from physical sales to the rise of streaming platforms and has adapted his label’s strategies accordingly.

In this exclusive interview, we delve into Heymann’s wealth of experience and knowledge. From the early days of streaming to the future of classical music, Heymann provides a candid and insightful perspective on the challenges and opportunities facing both seasoned musicians and emerging artists.

Nikhil Sardana: Can you share the story behind the founding of Naxos Music Group and what inspired you to create a classical music label focused on affordability and accessibility?

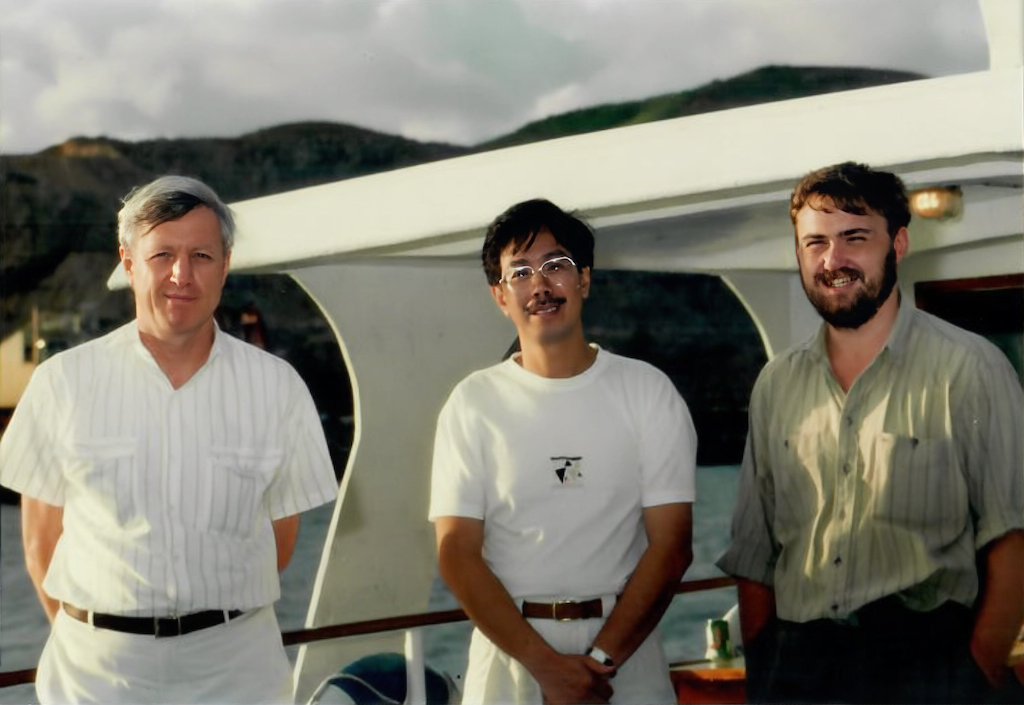

Klaus Heymann: I originally came to Hong Kong to open the office of an American military weekly newspaper due to the Vietnam War. After working for them in Germany, I opened their Hong Kong office. Later, I ventured into businesses like selling cameras and watches to the US military in Southeast Asia. This led to my involvement in the audio business, including working with Bose Corporation. I started organizing concerts in Hong Kong and distributing classical LPs from Eastern Europe.

One day, I invited artists to perform in Hong Kong who couldn’t find their own records. That’s when I realized there was a gap in classical music distribution. I started my own label, Marco Polo, and recorded with orchestras like the Singapore Symphony and Hong Kong Philharmonic. Eventually, I expanded into recording orchestras from Slovakia, Czech Republic, and Hungary.

In 1986, my wife and world-class violinist, Takako Nishizaki, suggested recording well-known classical pieces. We wanted to make these recordings affordable and decided to sell CDs for the price of LPs. This idea led to the creation of Naxos.

We initially faced distribution challenges, so we set up our own distribution companies and expanded to various countries. Over time, Naxos became a global distributor of classical recordings, working with numerous labels.

In the mid-1990s, we ventured into online music distribution. Despite initial scepticism, we saw the potential of the internet for music distribution. We continued to adapt to changing technologies, including the development of Naxos Music Library and embracing digital distribution. Throughout this journey, our focus has been on affordability, accessibility, and innovation. We’ve always strived to stay ahead of the curve and adapt to the evolving music industry landscape.

So, that’s a brief overview of how Naxos Music Group came to be, combining a passion for classical music with a vision for making it accessible to all.

NS: Over the years, Naxos has become synonymous with a vast catalogue of classical music recordings. How do you decide which works and artists to include in your repertoire, and what criteria do you use to maintain a balance between popular and lesser-known compositions?

KH: Initially, I based our selection on a printed catalogue, marking works with over 10 recordings. This formed the core of our first 100 Naxos recordings. We started with popular pieces, like my wife’s Four Seasons and Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata.

Gradually, we expanded our repertoire, filling out cycles and exploring lesser-known composers like C.P.E. Bach. As we covered most standard repertoire, we continued to adapt. Our Marco Polo label focused on world premiere recordings, inspiring others to do the same.

Over time, we acquired other labels with diverse repertoires. Today, we have an abundance of repertoire across our labels. While we have a few star artists, coordinating their projects can be intricate. For example, when two artists wish to record the same piece, it presents a challenge. In the end, our goal remains to offer a wide range of classical music to our listeners, including both popular and lesser-known compositions.

NS: Naxos has embraced digital distribution and streaming platforms, adapting to the changing landscape of the music industry. How have these technological advancements influenced Naxos’ business model, and what opportunities and challenges do they present for classical music?

KH: Before 1996, there weren’t any streaming platforms for labels; it was all about downloads. The positive aspect is that the business has become more profitable compared to selling CDs. We’ve eliminated inventory and shipping costs. With our existing infrastructure from running music libraries, we can efficiently distribute digital files worldwide. So, on one hand, it’s been more profitable, and we’ve reached larger audiences.

However, there’s a drawback. Streaming listeners often don’t engage with music as intensely as CD buyers did. I remember when I brought a new CD home, I’d listen with full concentration through my high-quality music system. Nowadays, I stream through wireless speakers in my living room, which lacks that same level of engagement.

The business has been simplified in many ways, but data analysis is now complex. We receive billions of tracks monthly, and we have to analyze and report this data to labels. It’s a challenging task. To deal with this complexity, we’ve partnered with specialized digital distribution companies like Fuga.

NS: In today’s digital age, how do you envision the role of record labels like Naxos in supporting and promoting classical artists as the industry evolves?

KH: Well, in the early days, artists could upload their recordings themselves, and some still can. However, now we’re seeing the rise of AI-generated tracks with three billion uploads a year. How can an artist stand out in such a crowded space? The reality is, only 25% of uploaded tracks get significant attention, and the rest often go unnoticed, even in the pop genre.

This is where record labels become more important than ever. They not only handle audio but also focus on video content. We now aim to record both audio and video with artists, even though video production can be costlier. These videos are often shared on platforms like YouTube and can open doors for artists.

Labels play a crucial role in helping artists gain visibility and navigate the competitive digital landscape. They are instrumental in securing placements on platforms like Apple, which often require video content. So, despite artists having the ability to upload directly to streaming platforms, labels remain essential in promoting and supporting classical artists.

NS: What insights or advice would you have for aspiring musicians and classical music enthusiasts navigating the ever-changing music industry landscape?

KH: In the past, I used to speak frequently to music students and offer advice. I often asked them what percentage of them expected to make a living solely from playing their instrument, and the answers were typically low. My advice to anyone pursuing a career in music is to learn as much as possible about the various facets surrounding music.

This means going beyond just mastering your instrument. Learn how to make a music video, upload files, and even delve into coding if possible. The idea is to equip yourself with a wide range of skills related to music. Even if you can’t find a traditional music job, you can still find opportunities connected to music.

Additionally, consider learning how to arrange music, compose, or create new works. This can open up new avenues, especially when you encounter unconventional instrument combinations that lack established repertoire. So, the key advice remains: Learn as much as you can beyond your primary instrument.

NS: Where do you see the future for the classical music industry?

KH: The classical music industry is vast, with various components like opera houses, orchestras, music schools, and more, contributing to a yearly turnover that likely reaches hundreds of billions of dollars. While the classical record industry has evolved, streaming and digital platforms are becoming more prominent.

In the future, I foresee the emergence of genre-specific streaming channels, akin to the Naxos music library, focused on classical, jazz, world music, and other genres. Established platforms like Spotify, Apple, Amazon, and YouTube may incorporate video content. This will create a vast and diverse streaming universe. With the backing of this substantial classical music enterprise, the future of classical music remains promising and adaptable to changing trends.