Music, Pedagogy, and Personhood

In its original Greek form, “pedagogy” means “to lead a child,” from the roots pais: child and ago: to lead. This suggests that education is inherently directive and necessarily transformative, but the question is what “leadership” and “transformation” mean and ought to entail. Philosophically speaking, pedagogy is a “thick” concept, i.e., one that derives its content entirely from the practice that it seeks to grasp. Concepts such as “rectangle” and “to the north of” can be explained in so many words without room for ambiguity, but one can only grasp what it means to be a teacher or a student by actually being a teacher or a student. Somewhat akin to being in “love,” we might say. If the state of being in love could be defined and explained once and for all, the variety of human attempts to capture that feeling would suddenly lose all relevance.

What, then, might it mean to lead a child into the world of music? This is a question of far greater social significance than the problem of how the technical aspects of music can best be taught. Issues of technique have been addressed by a wide range of scholars and practitioners for at least a century, among whom Zoltán Kodály is only the most famous. If we want to stay true to the original meaning and intent of pedagogy, however, then the question of how music might affect the personhood of children, and what it means to be a musician at heart even if not by profession, must be broached.

There are good reasons why these issues are rarely addressed head-on. Music is both an extremely abstract and a viscerally immediate art form. Without some knowledge of the technical apparatus of music and its unique language (where it exists), it is difficult to write about music confidently, even if one is interested primarily in questions of musicianship that exceed the technical confines of musical literacy. On the other hand, professional musicians rarely have the luxury of time to raise such questions, since music remains a less-than-fulfilling vocation for most practitioners in monetary terms.

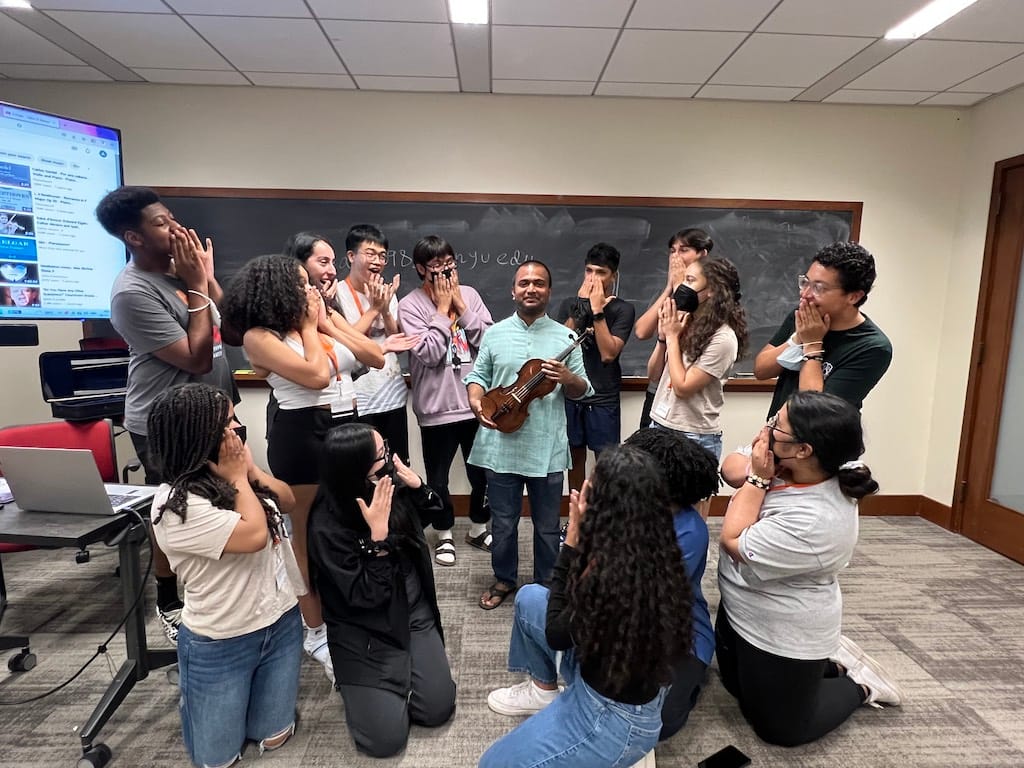

As a child and young adult in India, I had the good fortune of learning the violin from two extraordinary teachers during the most formative period of my life. Although I am neither a professional musician nor a music teacher at present, I find it easy and even necessary to identify as a “musician.” Indeed, when I was grappling with the question of how to write about reflections on the ethical status of caste norms in early modern Bengal, I zeroed in on the poetry and music of Rāmprasād Sen (c.1718-1775), the Sāhebdhanīs, and the Bāuls as one of my archives. And when I was teaching rising high-school seniors aiming to become first-generation college students at Princeton University last summer, I used music to build bridges with my students. It had occurred to me that that would be the best way to connect with people whose life experiences I did not share, and though I cannot explain exactly why I thought so, it worked.

Music, then, informs my personhood deeply, even though it is by no means the only thing that does so. Living in the United States far away from home, I often think about how and why music came to shape so much of my being. Undoubtedly, my parents played a major role. As a child, I was moderately fond of singing and took singing lessons, but football, cricket and the Cartoon Network captured my imagination far more. It was my mother’s wish that I learn the violin, which she had begun to learn as an adult but had to give up owing to professional and familial demands. For his part, my father gave up countless Sunday mornings to take me to lessons, and many of those journeys have tales of their own that deserve separate recounting.

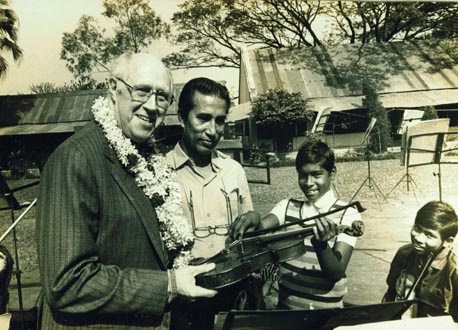

All of that effort bore fruit, however, only because my two teachers led me into the realm of music with immense love and care. The duo has (had) very different styles, but my own approach to teaching has been influenced by both. My first ever lesson was with Ananta Makhal (1937-2012) at the Oxford Mission in Kolkata on April 24, 1998. Five years ago, on the twentieth anniversary of that remarkable day, I reminisced about the beginning of it all and why I still remember it so fondly. This week, my twenty-fifth musical birthday coincides with my transition into a full-time pedagogue, and the time feels right to recollect about the effect on my personhood of Abraham Mazumder (b.1958), my second teacher and an inspirational figure for countless students including myself.

It will take an entire book to give a full account of what I have learned from Mr. Mazumder. Instead of attempting the impossible, therefore, I am going to recount a particular lesson from February 2004, which has a bearing on the larger question with which I began: the relationship between music, pedagogy, and personhood. The story is deeply personal and by no means generalizable, but the capacity to learn from and identify with the experiences of others is one of the things that makes us human. In the spirit of such learning, I hope to use my personal experience as a potential pathway into collective wisdom.

Most Kolkatans would probably agree that February is one of the most pleasant months in the city. March already feels like summer, and February is the only real month of spring. Occasionally, after a couple of slightly humid days, we are blessed with spring rain. The smell of wet earth wafts in the air and envelops the city with a sense of calm. Those are my favorite days, and though I may just be imagining this, I think Saturday, February 14, 2004, was one such rainy spring evening. My lesson was important since we were just a week away from a concert at St. Paul’s Cathedral on February 21. I was particularly anxious because this was the first time I had been tasked with being a soloist. My mandate: the well-known Gavotte by François Joseph Gossec.

I was by no means a beginner on the violin at the time, and the Gavotte is a short, not-too-technically-challenging piece. Performing as a soloist for the first time, however, is bound to give the jitters to most 14-year-olds. It certainly did to me. On top of all that, final examinations were ongoing in school, and I had to take a test on the morning of the 21st as well. I had spent the past several weeks practicing the basics – intonation and bowing especially – in a vain attempt to convince myself that repetition would ensure zero mistakes during the actual performance. What I remember most about the lesson on February 14, however, is how unconcerned Mr. Mazumder was about whether I made a mistake or two at the concert. What mattered, he insisted, was not whether I got every note exactly right all the time, but how I played what I did. You need to play like a soloist, he said.

But what on earth does it mean to play like a soloist? And how can one even begin to understand its meaning if it cannot be articulated more clearly in language? Looking back, I realize of course that what Mr. Mazumder meant was the personality and presence that a soloist brings to the stage. It is the magnetism, the indescribable energy and passion that the best performers from Elvis Presley to Itzhak Perlman were all able to conjure up whenever called upon. That excess of life draws the audience close to the performer and can even generate feelings of love. Once this bond is created, listeners are always willing to forgive a couple of technical slip-ups.

All of this makes sense to me in retrospect as a 33-year-old, but I would be lying if I said that my 14-year-old self was able to grasp it. I had always been good at concepts that had clear and objective boundaries, and, unsurprisingly, mathematics was my best subject in school. Playing the violin does have a technical dimension, of course, and I never had any trouble understanding it. In 2004, I was already playing violin sonatas by Mozart and Beethoven during my regular lessons with Mr. Mazumder. But while I was certainly moved emotionally by what I played, I approached pieces of music as complex assemblages of notes and sounds rather than as pathways into an exploration of human relationships and the constitution of one’s personhood.

When I was asked to play like a soloist, therefore, I treated that statement itself as something that could be broken down into constituent parts with distinguishable content. I tried to follow the dynamics more closely, I used greater bow pressure, and sometimes I unwittingly increased the tempo in an attempt to make things more exciting. I also paid closer attention to phrasing, which did draw some praise from my teacher. Overall, though, Mr. Mazumder was unsatisfied. Unable to find words for what he was trying to communicate, he played a few phrases himself, hoping that I would catch the trick. But I didn’t. Eventually, he recorded the piano accompaniment on the Roland keyboard he was using and put it on a loop for me to keep playing until I showed signs of improvement.

The lesson was nearing an hour by that point. Both of us were beginning to lose patience, but I was too scared to even think of saying that I was getting late. I am also stubborn, and I wanted to crack the code, so to speak. At that moment, that was probably the only thing I had going for me. Mr. Mazumder sat across the room near a window and waited to hear me play the piece a few more times. He composed his thoughts and then uttered a sentence that I will never forget: “Tui ābār tor shell-er madhẏe ḍhuke jācchis” (you’re retreating into your shell once again).

Magic! With a few words, my teacher helped me to modify my approach to the problem. What his statement made me realize is that being a soloist means bringing something deeply personal to what one is playing. One can analyze the notes as much as one wants, but what distinguishes one rendition of a piece from another is that personal dimension of musicianship. The insider term for this is “interpretation,” and everyone has their favorite interpretations of Bach’s partitas for solo violin or Elgar’s cello concerto. Technique is the foundation of all musicianship but it is by no means the end. Many musicians achieve a good level of technical proficiency through proper training and practice. To be a soloist, however, one must bring one’s personality to bear on the music, which requires both introspection and courage.

In February 2004, therein lay the problem. As a 14-year-old, I had not even begun to engage with the question of who I was/am as a person. I had always been relatively shy as a child, and I was never good at making new friends. Gradually, by the time I was in sixth and seventh grade, I had established a reputation in school as a good student, a decent violinist, and a dependable teammate on the football field. In April 2003, though, I switched from St. Lawrence High School to St. Xavier’s Collegiate School, and the transition was not easy. For one thing, I missed my friends, and I knew that I needed to rebuild my reputation from scratch. Moreover, English was the primary language of communication at St. Xavier’s, and although I was good at it technically, I lacked the confidence to speak it fluently. By the end of my first year in this new environment, I had retreated into my shell quite literally, and I neither took any initiative nor spoke in class unless I had to.

Staying within one’s shell can be quite comforting. It minimizes the risks of conflict, and it takes away the anxiety of being misunderstood and criticized. Putting oneself and one’s “interpretation” out there can be scary, for one always worries that perhaps the interpretation is too personal and no one will understand one’s motivation for doing things one way as opposed to another. The fear of unfair criticism is not unfounded either, since far too many people treat it as a means to cut others down to size. Teaching children to come out of their shells, therefore, must also entail the teaching of empathy and mutual respect. Being a soloist does not mean dismissing the interpretations of others. Rather, it involves engaging in a dialogue about what meanings we can collectively share without disavowing the singularity of individual experiences.

I would not have been able to articulate any of this in 2004. Nor can I insist that whatever I did understand about my teacher’s statement had any immediate effect on my playing. I did realize, however, that who “I” am and how I came to be that person is deeply relevant to the art of performance. Mr. Mazumder seemed convinced that I had made some improvement by the end of the lesson, and perhaps he saw something that I cannot recognize even retrospectively. But as I prepared for the concert the next week, I remember feeling a great sense of freedom. Not worrying too much about the notes felt liberating, and it helped me to see what mattered. I was never going to be Jascha Heifetz, and no one would remember me for my interpretation of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. But I could do an interpretation of Gavotte by Anirban Karak that some people – albeit a handful – would remember. That means something, and it ought to be cherished.

The concert went well, or at least that is how I want to remember it. My performance was by no means the showpiece event – Beethoven’s Romance for Violin and Orchestra in F was also on the programme – but it was undoubtedly an important step in the development of my personhood. I was surprised by how anxiety gradually transmutes into exhilaration during an actual performance, and every performer knows how intoxicating that feeling is. My teacher had not only helped me to see things differently; he enabled me to enjoy the act of performance itself. I realized that putting my interpretation out there was full of possibilities for generating self-consciousness and for communicating with others what could not be said in words.

By the time I was in college, I had come to enjoy performing and I was able to consciously channel my individuality into my interpretations. I also recognized that ultimately, how well one can communicate with others depends not on technique but on life experiences. In February 2004, for instance, I had never been in love, and one cannot communicate feelings of love or separation if one has never loved and lost. “It takes a worried man, to sing a worried song,” as the American folk song goes. As I have grown older and matured (hopefully) as a person, I have been able to draw on a wider range of experiences to bring to bear on my interpretations. Though I perform very infrequently as a violinist at present, the lure remains, and more importantly, my love for performance has also affected my approach to teaching in general. Even when I am teaching history or social science, I bring my body and not just my mind to bear on the task. I walk around, I ask questions, I gesticulate, and I constantly write on the board. I enjoy the performative dimension of teaching as much as the actual content of what I teach.

Don’t get me wrong. I still feel the same anxieties as anyone else about making choices, taking a position, or criticizing another’s argument to defend my own. I try, however, to understand before I disagree, and I feel better after I say things, whether musically or in words. There is something incredibly liberating about standing up for things that one believes in, and we need to find a way to enjoy the process of dialogue itself. Whether I am playing music, writing academic articles, or leading children the best I can, I try to stay true to the same principles: our social practices are expressions of human relationships, and all art is an exploration of the shared meanings that we can arrive at through a dialogue about the singularity of our individual personhoods.

As a card-carrying historian, I cannot in good conscience overburden a single lesson in 2004 as the source of all insights that I ever gained from my teacher. Learning takes time, and it was undoubtedly a process. I had formal lessons with Mr. Mazumder for 7 years, and even beyond that I learned a lot from him as a member of the chamber orchestra, and as a teacher at the Academy that he founded. Nevertheless, we can only remember some parts of the whole at any given time, and we must try and build a picture of the whole as best we can from those parts. I have made an effort to do that, and I hope that my remembrance does justice to the love and care with which Mr. Mazumder taught me. The way he helped me to approach music has had an enormous impact on my personhood and my teaching style, and I thank him for nurturing me in his inimitable style.