“Music is the totality of what I do” – Pinchas Zukerman: In Conversation

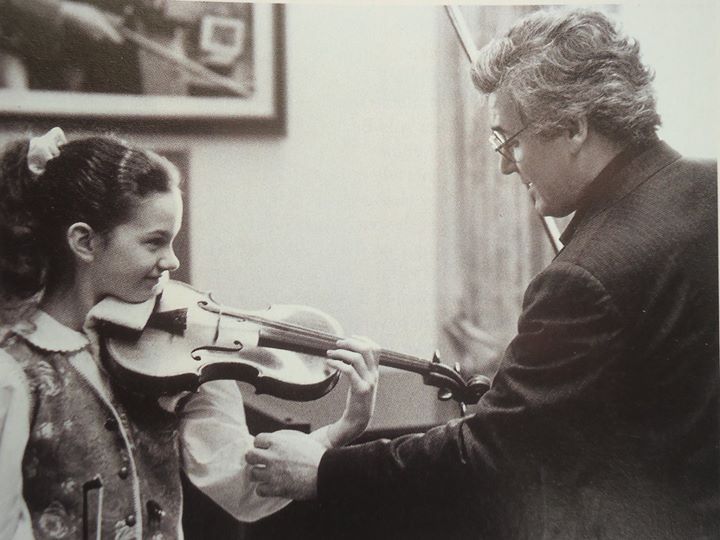

Pinchas Zukerman needs no introduction, but the sheer breadth and depth of his versatility and contribution to music, does bear recounting. His prodigious talent was recognised by legendary musicians Pablo Casals and Isaac Stern when he was a child in Tel Aviv. Sent to study at New York’s Juilliard School as a teenager, he went on to not only fulfil but surpass all expectations.

Violinist, violist, pedagogue, conductor, administrator: he has been all these, switching hats, or wearing them together, to dazzle audiences for over 50 years now. At 70, Zukerman still plays, by his own admission, “like a 30 year old”. The years have only brought a depth and thoughtfulness to his musicianship, while retaining the famous Zukerman clarity and sparkle.

Audiences at Edinburgh’s famous Usher Hall this weekend, will have the rare treat to see the maestro as conductor and performer, with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The repertoire will feature well-known masterpieces: Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, Elgar’s ‘Enigma‘ Variations and Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Tallis. The works, dramatic, brooding, dreamily poetic, with elements of comedy and wit to leaven the very substantial fare, are ideal showcases for Zukerman’s vast canvas of sound and mood.

A couple of days ahead of the concert, I had the privilege of an interview with Zukerman. It was a free-wheeling, wide ranging one, where he spoke of matters musical and extra-musical, revealing of a personality that cares deeply, indeed passionately, about the young talent he mentors, the legacy he has inherited and the values that drive him.

On his early influences and beginnings in music

The ability of one’s playing has to do with teaching, society, the cultural life a child will have from the teens onwards, and that’s where we fail every time, except with a few. I may be the exception to the rule because I had phenomenal teaching. I had extraordinary luck, and don’t forget the huge part luck plays! I had the greatest mentors that showed me the path to a very, very, very – and I keep saying “very, very” because it was – long journey, and I’m still doing it. At 70, I am still able to play like I am 30. But I was just practicing for one hour. That’s because my discipline and self-esteem comes from playing in tune, with a nice sound. How do you teach that to a 12-year old? You bang it in their heads and you say: “NO, DON’T DO THAT!”

Now, the biggest problem is separation. We all have separation problems. Everyone is different, everyone is handling it in a different way, yet nevertheless, the bottom line is separation. We are separating from being a baby, to being a teenager, to being an adult. Those are big emotional aspects. In my case, the violin was a friend. I didn’t know any of that when I was 15-16, but I had people who said, “You had better do it”. I also didn’t live with my parents (he was born in Tel Aviv, and after playing for Pablo Casals and Isaac Stern as a child, was sent to the Juilliard School in New York at the age of 14).

On the cult of the child prodigy, and the premium placed on virtuosity

I think there have always been child prodigies (he himself was one, born with perfect pitch, beginning his violin studies at the age of 5 with his father, a professional violinist, and entering the Tel Aviv Academy by the age of 8). People like Horowitz, Rubinstein, Rachmaninoff, Heifetz, these were all great prodigies. Probably in some ways they were even more amazing than those today, because they came from a culture that already understood the inner workings of music and art. Because of where it comes from: Europe, Russia—that’s where the music came from. Not India, or Japan, or Korea. It came from those countries and therefore those prodigies were amazing. They still are! Beethoven, Mozart—these are huge prodigies. They are the ones who have really cultivated the Western hemisphere in the last 500 years to make us who we are today as a society.

Where the difference lies mainly today, is with the YouTube and smart phone generation. The television was a wonderful vehicle many decades ago to make music more accessible to people, to those who could not afford to travel from, for example, Novosibirsk to Moscow, or London to Berlin, to attend a concert. Today we have a very different set of aspects of communication between people. Yes, the child is definitely brought to the forefront as something unique and special. Such children are indeed unique and special, always have been, always will be. The problems begin when you get to teenage life, one being the hormonal changes that take place. We know the brain is the most wonderful thing in our body, yet we know very little about it. So what happens to these children? During their hormonal change, they go through a stiffness, an idiosyncratic self-examination. At that point teaching is so important. The home today wants to bring their child more and more to the forefront. I see parents being the biggest pushers today, and that is the biggest problem I have! In our classes, I can tell you there are no parents allowed and no visitations for the person studying with us. Because it is my private time with that person, and it instills discipline.

When you have a child that is very talented, it is a hard aspect to develop that talent, because they are very precocious and curious. You have to slow them down and make them practice scales. Stop the Paganini Concerto! Casals told me about the G major scale—he spent two hours on seven notes. Imagine that! It opened up a whole new life for me. So I love, I adore, talent; it’s magic, but it has to be handled right.

Virtuosity is not a circus. Paganini didn’t belong in a circus—he developed an ability to play an instrument because his ability was unique, and he wrote amazing and wonderful music. When you are developing muscles, you need to play those virtuosic pieces in order to confront the muscle dexterity in your body. By the time you are 16, that dexterity is practically over, but you have developed something unique. Everyone is a little different: one will go further with it, one a little less. Virtuosity per se, is a good thing. It is society that takes advantage of that. I’m there to help kids. I know a bunch of them, 8, 9 years old and they play beautifully, with the sound of an old person, an old soul. Where does that come from? I don’t know!

On the use of technology to reach out to developing musicians

Bernstein was a genius and created some amazing things on television for children. That’s what we need to look at. Young musicians reach out to me all the time, and they say to me: could you show what you do? I say: no, because if I show you one little thing, who is going to show you how to do that tomorrow? The follow-up is so important, and we can only take so many.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CucWz4IYBJo

Technology can help that if it’s done right and used properly. The whole idea of the video conference, Skype, is unique. It can and does save lives. (Pinchas Zukerman is known as a pioneer in the use of video-conferencing and webcasting technology. He launched the career of Russian violinist Ilya Gringolts after seeing a video sent by the boy’s parents to him from Russia, arranging for him to study with Itzhak Perlman at Juilliard).The future for communication is bright, They say, would you play on Mars? I say, if I could I would.

On guiding and preparing young people for a life as professional musicians

I think one of the most important aspects of helping a young person is to make him play chamber music. We have summer courses and also in the schools, they play chamber music. (In 1998, Zukerman was appointed Director of the National Arts Centre Orchestra of Canada, where he founded the Young Artists’ Programme, which saw participation worldwide; he is the guiding spirit behind the Manhattan School of Music’s Pinchas Zukerman Performers Programme). Such a group is a lifeline to communication. Even at 10 or 12 years, we make them immediately play in quartets and quintets, and within a few days they become different people in their attitude towards music.

Consecutive weeks of lessons is another key element. So is warming up before the lesson. About practicing, Freud said that the brain can only take 45 minutes of every hour. So these 8 hour practices just leave a child frustrated, angry, and with bleeding fingers!

The greatest disappointment for young people is, you know, for every 3 or 4 geniuses we have hundreds who are not. It is a long journey and it takes great dedication. But they get frustrated at having to work in an orchestra. My response is: What’s wrong with that? Orchestras play the greatest music in the world. Furthermore, you are earning a living, which makes your confidence level go up. But they want to play in quartets! With whom/ How are you going to eat/ Where will you live? The really young ones say they’ll find some way. But they don’t. So we prepare them as much as we can to a better life in music. So far, cross my fingers, we are doing OK. We just celebrated 25 years of our programme at the Manhattan School of Music, and I must tell you, it was the greatest validation of what great music-making can be. And that’s all: you have to teach and have a lot of patience. You have to show the path and not fake it. It is teaching the students how to teach themselves. And it takes time, because the brain is the slowest computer there is!

On the many platforms from which he engages in music and what the future holds

That’s what I do and who I am. Music is my life, the totality of what I do. I eat and breathe music. It helps me in every other capacity in life, to understand people better, politics better—not that I like what is happening today, but I can’t do anything about it except keep playing the violin.

I am also a husband, with a wonderful wife, a father and grandfather with wonderful children, so I am a very lucky person. I have had an extraordinary trip, and hope to continue sharing that trip with people that like to listen. I don’t divide it up.

Again, one has to go back to where the foundation was laid and it was laid at home with a conscious and conscientious effort to be real. You know my greatest and oldest friend is Zubin Mehta. His father was a violinist who threw him and his brother into the orchestra, planned to give Zubin the best possible musical education. So the whole family moved to Vienna and then to America, and the rest is history. So, a lot starts in the home.

All the greats of the last 100 years, Barenboim, for example, who is a phenomenon, Horowitz, Toscanini…they are all unique, but they all stem from the value system, and that value system is the score. If you start fooling around with that value system, you are finished. The capacity and ability of a person is how hard and honest they are with their own being.

For the future, I hope to build more institutes, to give institutes the ability to build on what they have already. And that requires money. And if I can help with that to raise the ante, it would be to contribute. There are still extraordinary amounts of money that are not being dedicated to the non-profit areas, not just music, but ballet, museums, languages, art schools. I hope that I can continue working in my own way to establish a better place for the generations to come.

On performing in India, Indian audiences and India in general

Audiences are all the same. If you play well, and with a beautiful sound, they love it. Because audiences are very smart, keen: they may not know how or why it’s happening, but they know if it is good. (He performed in Mumbai in 2016 with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Zubin Mehta). I haven’t been to other parts of India, but I hope to do that without going to play. I just want to go and see places. If you saw what I wear, you’ll say I am an Indian, because that’s all I have now! All those wonderful shirts from Mumbai. I love the food, I always have. Zubin and Zarin are my family and in Los Angeles I would go over to eat the curry made in their home.

The heart and soul of a country comes from their art forms and how to behave with each other. And Gandhi—he was a miracle. He showed us the way.