Music and Memories

Friday, April 24, 1998, began as a usual day in the life for me. It was an overcast morning in Calcutta, as it tends to be on days when the city is blessed with April showers after days of sweltering heat. I do not remember much from my time at school, except the widespread sense of anticipation that everyone felt about the Sharjah Cup final scheduled for the evening. It was Sachin Tendulkar’s twenty-fifth birthday, and just a couple of days ago his blistering knock of 143 had propelled India into the final against Australia. Surely he would not let down an entire nation’s hopes on his birthday? Or would the burden prove too much for his young shoulders? The tension in the air was palpable.

Two decades later, I can recall April 24, 1998, as if it were yesterday. That remembrance however, is provoked not just by the cricket, but also by a chain of events that evening; ones that have proved more significant than I would have dared to imagine at the time.

I remember returning home in the afternoon eagerly, and feeling let down that Australia had chosen to bat first. The game was being played at Dubai, and the second innings would begin only around 9:30 pm in the evening. How could I watch Tendulkar bat late into the night given I had school the next day?

As it turns out, I had other problems to deal with. My mother returned from work soon, and reminded me that the first violin lesson of my life was scheduled for later that evening. I was too engrossed in the game to notice, and soon it started raining heavily. When the torrent didn’t stop about half an hour later, my parents suggested that we reschedule. I was relieved; at least I’d be able to watch the first innings undisturbed.

Soon the rain stopped however, and there was still time for us to make it to the lesson. My parents urged me to go, and I was beside myself. How could they revoke a promise made just a few minutes earlier? From my perspective, it was nothing short of betrayal. I was eight, and too immature to inhabit my parents’ anxieties. They were both first generation migrants into the city, and had found it difficult to tap into the networks of information that in the 1990s still remained inaccessible to many. It had taken a lot of effort on my mother’s part to find a dependable reference, and she was worried that missing the first lesson would mean a lost opportunity for her son. She had craved for such an opportunity all her life, but the burdens of family and her own career as a doctor had proved too much.

It is a testimony to both my parents’ apprehensions and their love for me, that the resolution to the problem came in the form of a bargain. I agreed to go, but only once I was assured that I could watch the Indian team bat late into the night as long as Sachin Tendulkar remained on the crease. It was one more burden to bear for the little master, even though he could scarcely have known it.

My lesson was at the Oxford Mission at Behala Chowrasta, a twenty-minute auto ride from New Alipore, where we lived at government employee quarters at the time. The Mission was a venerable institution, built by the Bishop of Calcutta with support from the Oxford University way back in 1879. As I walked into the premises, I remember feeling overwhelmed by a sense of serenity. Here was a space in the heart of the city with greenery, open fields, chapels and music rooms all in one. It was a long walk from the main entrance to the teachers’ quarters, and the sight of children playing, combined with the general sense of community that the place seemed to exude, already made me forget the events of the last couple of hours somewhat.

I also remember very distinctly the living room of my teacher’s apartment that was being used as a lesson space. There was a couch on one side for parents, a chair in the middle for the student with a music stand in front, and a bed on the other side. What struck me most about the room however, is the vast amount of sheet music that filled it. Every shelf, spare piece of furniture and even the bed had been used up almost completely. Strangely, that messiness only brought a sense of fulfillment that I wasn’t able to understand even as I felt it. I can scarcely express the feelings evoked by that distant memory even today, except to say I wouldn’t change a thing.

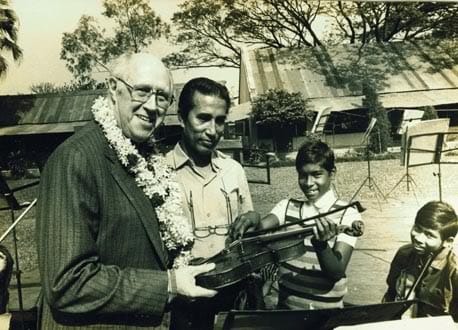

My teacher, Ananta Makhal, was in his late-50s at the time. As he sat on the edge of the bed, his eyes twinkling from behind his large spectacles, he smiled at me. It was at once reassuring and welcoming, and I felt at home. There was a sense of knowing anticipation in his demeanour It was almost as if he knew what to expect from me and exactly how to guide me, although I had absolutely no clue what was about to happen. Half an hour later, I was a different person. It will not be an exaggeration to say that my life has never been the same since, although that insight could only ever be a retrospective one.

Everything my teacher introduced me to seemed to make sense. I felt no particular discomfort holding the violin and adjusting my body for the purpose, the bow-holding seemed easy enough too, and the notes on the page, although mere symbols at first, made sense once I understood that they indicated where on the strings I had to put my finger and how long I had to hold them in place. Not only did we cover an extensive set of notations that day, I also managed to play an octave of the D major scale at varying rhythms and tempos! I remember feeling a sense of joyous excitement so profound, that before going off to school the next morning, I was playing and showing my sister what I had learnt.

Back to Friday evening though, for the story has not yet ended. I went back home feeling happy, had dinner hurriedly and started watching the game. I remember that my grandmother on my mother’s side was visiting, and she along with my sister were to sleep in the same room. So I was instructed to turn off the sound, but as per the bargain, I could keep watching as long as Tendulkar continued to bat.

For anyone who is a cricket buff or for anyone who grew up in the 1990s, the rest might be familiar. Australia had scored 272, a difficult target to chase down in those days. Tendulkar responded by playing one of the best innings of his life that night. He scored 134 without being dismissed, and almost single-handedly led India to victory. I was too tired to stay awake till he reached his century, and did not even know the result of the game till next morning. My father had at some point come into the room and switched off the television set.

For the past two decades, music has shaped my being, bringing a different meaning to every event than what a non-musical life might have brought. Besides my immediate family, my music teachers and my musician friends remain the best links to my past. My first teacher, Ananta Makhal, passed away in 2012, and I have always regretted not being able to share with him my memory of our first encounter. Surely though, what matters is what he taught me, and the warmth and care with which he wrapped his teaching. I will be forever grateful to him, but even more to my parents, whose love for me and hopes for my future came together to gift me that wonderful combination of cricket and music that evening. As for Tendulkar’s sublime innings, in his Man-of-the-Match interview, he dedicated it to his wife as a gift on his birthday. From my perspective though, the angels had heard my prayers and decided to put me to sleep happy.