Maria Forsström and Bengt Forsberg Discuss Mozart’s Requiem

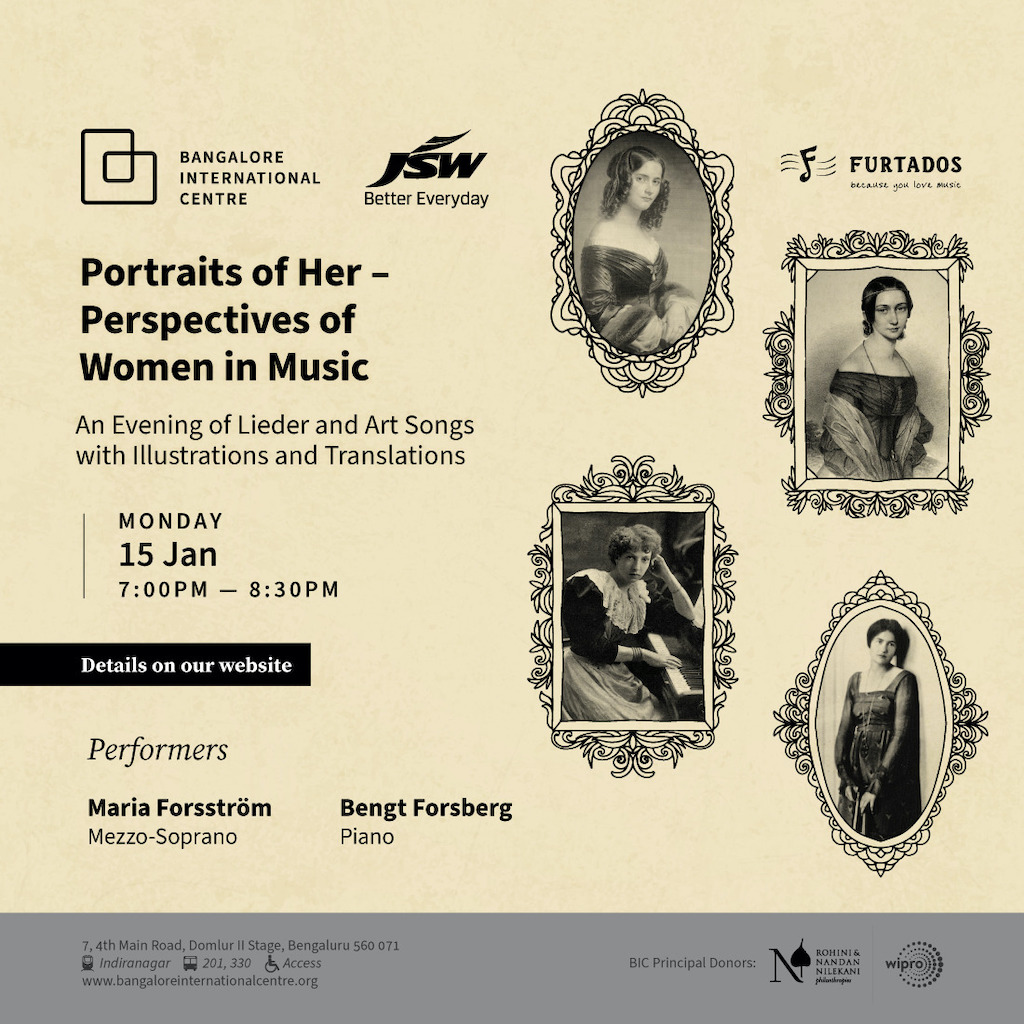

Maria Forsström, a versatile Mezzo-Soprano, initially studied church music, piano, and conducting before transitioning to singing at 33. Her performances span from Baroque to late Romanticism, collaborating with global orchestras and conductors like Christoph Eschenbach. Maria’s accolades include a prestigious 1st prize at the Varazdin Baroque Festival and appearances at renowned music festivals and recording labels.

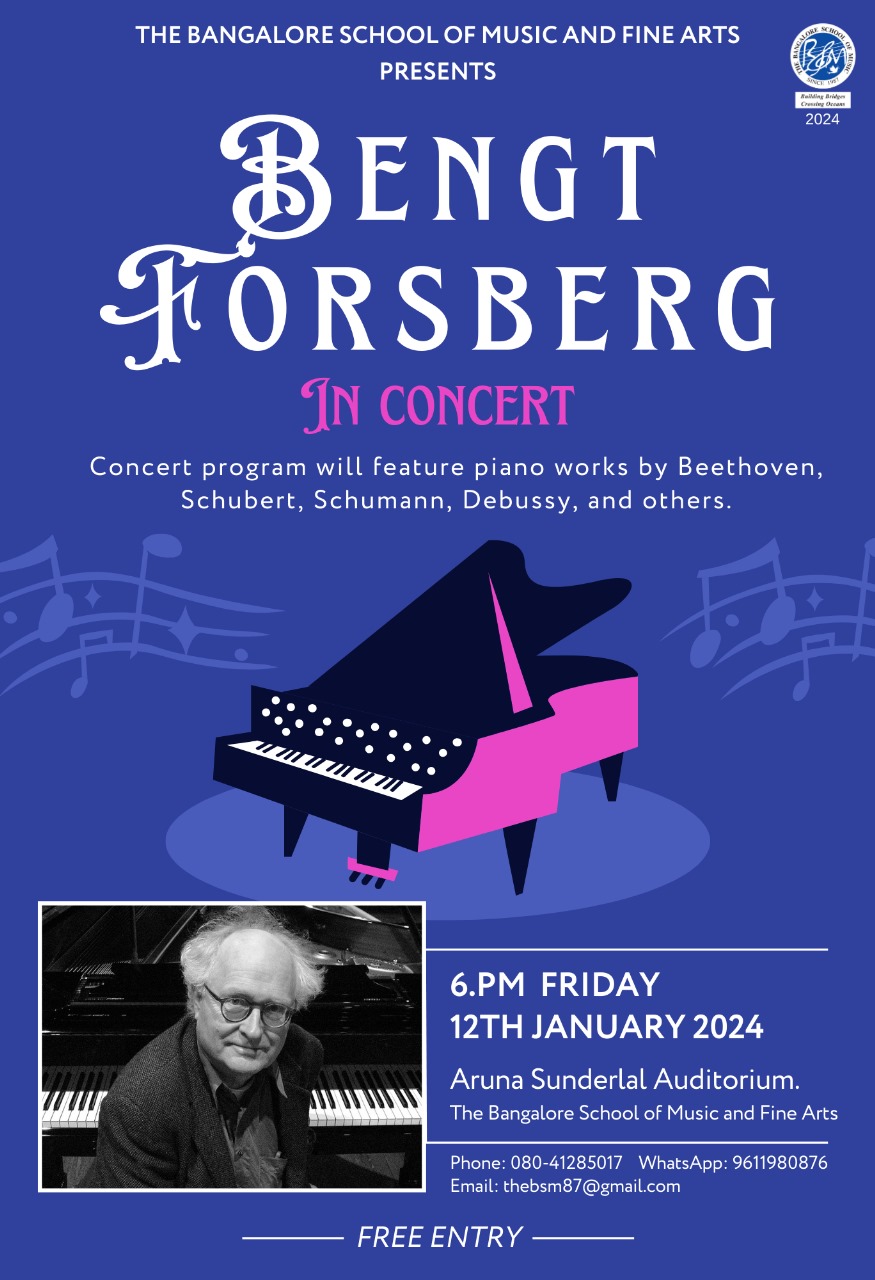

Bengt Forsberg, a distinguished pianist, honed his craft at the Gothenburg School of Music and Musicology. Famed for chamber music, Bengt’s collaborations with prominent artists earned him a Grammy Award for Best Classical Solo Vocal Album. His repertoire extends to uncovering overlooked compositions by revered composers and directing a prominent chamber music series in Stockholm. He’s been a member of the esteemed Royal Swedish Academy of Music since 1997.

The following conversation between Maria Forsström and Bengt Forsberg delves into the essence of Mozart’s Requiem and the intricacies of interpreting classical music. Their insights span from historical contexts to the transformative power of live performances, reflecting their commitment to nurturing musical talent and promoting classical music across cultures.

Serenade Team: Given the Mozart Requiem’s mysterious commission and completion posthumously, what draws you to this piece, and what emotions or challenges does its history evoke in your performance?

Bengt Forsberg: I find Mozart’s Requiem incredibly gripping, especially considering it might be one of his last compositions before his untimely death in poverty. The use of the D minor key, which Mozart employed in other emotionally charged pieces, adds a haunting depth to this Requiem. Unlike some of his other works in D minor that have a more outgoing feel, this one goes straight to the heart with its serious and direct tone.

Maria Forsström: What strikes me is how this piece embodies the Enlightenment era, reflecting those ideals while also revealing Mozart’s deep thoughts and faith. The texts, dealing with the afterlife and the weight of our actions on our souls, were genuinely religious beliefs of the time. As performers, we must respect and internalize this context, understanding the gravity of these themes despite our more secular world today.

It’s awe-inspiring to see how widely performed this Requiem is globally. In a time when religion might not hold the same place in society, it’s crucial to approach it with the same seriousness and reverence it was intended to evoke. Regardless of personal beliefs, it demands a genuine introspection from both performers and audiences, reminding us of the profound reality it addresses.

Bringing this piece to places like Bengaluru feels truly special. Its universal appeal transcends cultures and beliefs, touching the core of human emotions and existential contemplation. That’s the power of Mozart’s Requiem—it remains relevant and impactful across time and geography.

ST: Maria, how does collaborating with choirs and orchestras influence your interpretation of Mozart’s compositions? Any unique insights or challenges that arise in such collaborations?

BF: For me, delving into this score reveals so much depth already embedded within both the music and the profound texts it carries. I don’t feel the need to inject my own interpretations; rather, my focus is on bringing clarity to the performance. It’s about organizing the ensemble, ensuring everyone shares the same intentions and understanding, particularly in this new endeavour collaborating with Indian musicians.

MF: Working with local talents instead of relying on a Swedish orchestra presents a thrilling opportunity, but it’s also a significant challenge. My role mainly revolves around handling the practical aspects of this unique collaboration. With a tight two-week timeline to merge the orchestra and choir, I’ll spend time with the strings, striving to achieve something unprecedented in this performance.

I want to stress the seriousness of this piece. It’s not just a showcase; it demands reverence, regardless of personal beliefs. Despite its vibrancy and multifaceted brilliance, it’s not something to be approached casually. It’s alive, vivid, and brimming with genius, but it commands a level of respect and gravity that cannot be ignored. This piece compels attention and dedication, offering an experience that goes beyond mere entertainment.

ST: Bengt, your reputation in chamber music is renowned. How does this experience influence your approach to solo performance and collaboration, especially with Maria in vocal-piano partnerships?

BF: I feel incredibly fortunate to have a diverse repertoire that allows me ample opportunities for solo performances. Chamber music holds a special place in my musical journey, often collaborating with exceptional singers like Maria or esteemed Swedish vocalists such as Anne Sofie von Otter. These experiences add immense pleasure and depth to my life as a musician.

Occasionally, I also have the chance to perform with orchestras, like the upcoming collaboration I’m eagerly anticipating. Meeting and performing alongside Maria, who’s not just a conductor but also incredibly multi-talented, promises to be a rewarding experience. Her versatility and skill are truly remarkable, and I look forward to sharing the stage and creating music together.

ST: Maria, transitioning from conducting to vocal performance, how has this shift influenced your musical approach and interpretation of pieces, particularly works like the Requiem?

MF: My identity revolves around being a singer. My vocal teacher, Mr. Jonathan Morris in Lugano, Switzerland, recently mentioned something that deeply resonated with me—he expressed that all instruments are essentially imperfect imitations of the human voice. It struck a chord because, for me, singing is not just a skill; it’s my instrument. It resides within me, and I approach music from that perspective.

When I perform, I strive to infuse the orchestra with that singing quality. I aim to communicate that when I sing, it’s about creating long phrases rooted in breath. I want the strings to echo this organic, breath-like quality in their playing. Similarly, when I work with singers in the choir, it’s easy for me to convey what I envision because I can guide them technically, from the standpoint of singing technique. It’s not solely about producing beautiful tones; it’s about painting the words, infusing them with meaning.

My goal is for the orchestra to mirror this approach, painting the meaning behind every word through their instruments. I seek to bring out the expressive nature of music, to convey not just the notes but the emotions and significance behind each musical phrase. Expressive—it’s a fantastic word that encapsulates my approach to music.

ST: How do live performances, like the upcoming concert in Bengaluru, contribute to the depth and resonance of interpreting classical masterpieces like the Requiem?

BF: A live performance is always preferable to a recorded one, of course, because you can feel that everybody is striving for something higher and better. Every performer is supposed to genuinely want the listener to join in a complete and total experience of the whole piece. So, I think it’s quite obvious when you have a live performance. It’s a matter of life and death, actually. And there’s also a very physical, tangible aspect to it. When you’re singing or playing, you’re actually manipulating sound waves and the air in the room. You’re projecting energy, making the entire room vibrate with sound waves and your resonance. So, we actually affect the audience physically.

MF: There’s a therapeutic discipline called sound healing that a friend of mine practices. He stands next to someone’s spine and creates strange sounds directly on the vertebrae. It’s completely amazing. This is proof that sound waves affect us and have an impact on us. You’ll never experience that with a streamed performance. Also, there’s a more metaphysical aspect to it. It does something to you when you have a huge choir and an orchestra right in front of you. It’s a massive impact.

ST: As experienced performers, how does your journey influence your approach in educational settings, particularly regarding the importance you place on nurturing musical talent?

BF: One of the most important things for me is mastering the technical aspect of every piece. That’s a given. But what I strive to impart to people is the uniqueness within each piece. I want them to experience immense joy. Joy is essential. Many musicians lack that joy; they feel the routine and understand how to perform at a high level, yet they miss that ecstatic feeling, which I believe is crucial. I am quite positive about that.

MF: My advice to aspiring musicians is simple: practice extensively, but practice smartly. To do so, you need to learn how to learn effectively. There’s an ancient Sufi discipline about this, aligning with modern neurobiology. Constructive learning techniques are crucial. Negative instructions hinder learning; they’re counterproductive. As a curious learner myself, I’ve delved into the science behind teaching and learning. Understanding how the brain responds to constructive instruction has become my focus. It’s about pinpointing what needs addressing precisely, reducing struggles in understanding. Learning from sports training methods, like ‘The Inner Game of Tennis,’ has taught me the power of mental preparation before physical practice. This mental groundwork before physical execution fascinates me. It emphasizes the significance of extensive, strategic practice.

ST: How do you perceive your role in preserving and promoting classical music for contemporary audiences, particularly in the context of cross-cultural dialogues?

BF: It’s clear that music from centuries ago holds immense value for new generations, offering constant richness and significance. I firmly believe that classical music has a vibrant future, with numerous talented young musicians emerging. However, I’m slightly concerned about the pervasive presence of pop music, often overshadowing classical music’s place in people’s minds. Understanding classical music demands engagement and effort from the listener.

MF: Western classical music holds profound significance like preserving historical cathedrals or ancient texts. It enriches our world, offering timeless masterpieces that resonate with individuals, revealing new layers within themselves. Bengt and I aim to strengthen Western classical music in India, advocating for concert halls with excellent acoustics that benefit both Western and Indian classical music. Our goal is to make music accessible to all, even those unfamiliar with its technicalities. As artists, our pursuit of knowledge and exploration never ends. I’m currently exploring classical ballet, a testament to the ongoing joy and fulfilment that learning brings.

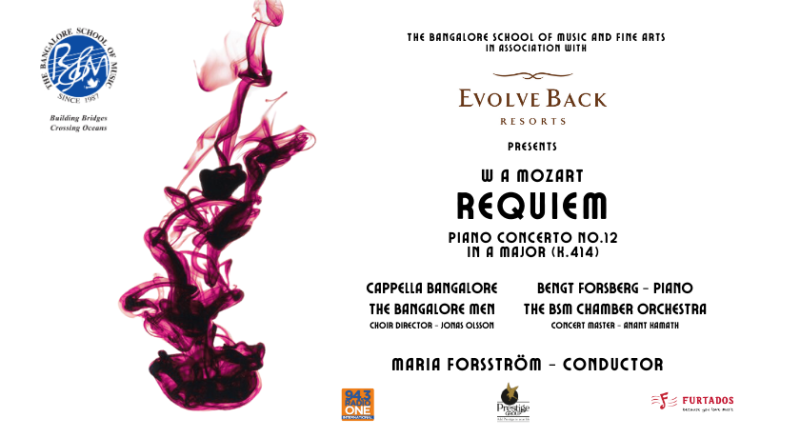

Experience an unforgettable musical performance at the Chowdiah Memorial Hall in Bengaluru on January 19th. The Bangalore School of Music (BSM), in partnership with Evolve Back Resorts, presents a unique version of the Requiem featuring Cappella Bangalore, The Bangalore Men, and the BSM Chamber Orchestra, accompanied by soloists Payal John (soprano), Vinaya Vinodkumar (alto), Benson Chacko (tenor), and Nivedh Jayanth (bass). BSM welcomes back esteemed chamber musicians Bengt Forsberg (piano/organ) and Maria Forsström (conductor) from Europe. Together with the talented musicians of BSM, they will present the Requiem and Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 12 in A-major.