Mapping the Musical Genome: The Gibbons Family

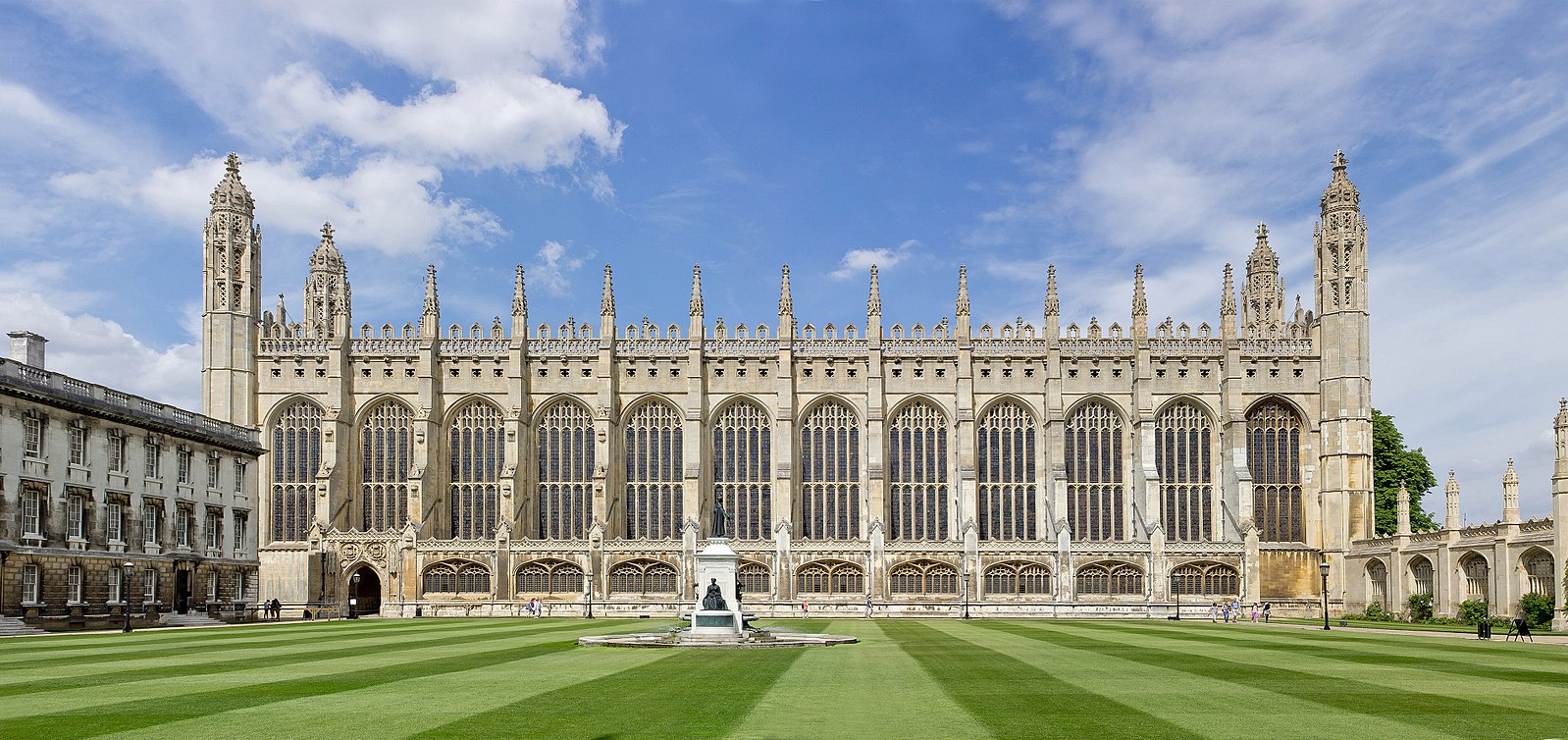

Orlando Gibbons (1572-1625) was born in Oxford, son of a town wait—essentially a town musician whose duties included playing his instrument for the townsfolk, welcoming Royal visitors, and leading processions on civic occasions. William Gibbons moved back and forth between Oxford and Cambridge, and young Orlando became a chorister at King’s College, Cambridge in 1596. Mind you, music was certainly part of the Gibbons DNA, as his eldest brother Edward was actually master of the choristers. Orlando was an extremely skilled keyboard player, and he is habitually counted among the finest of the great virginalists.

He developed a supreme compositional technique early on, and his technical and expressive mastery focused on the inventive use of rhythm, counterpoint, and sonority. It is not entirely surprising therefore that Glenn Gould once named Orlando Gibbons as his favourite composer. Gould compared Gibbons to Beethoven and Webern, suggesting “…Like Beethoven in his last quartets, or Webern at almost any time, Gibbons is an artist of such intractable commitment that, in the keyboard field, at least, his works work better in one’s memory, or on paper, than they ever can through the intercession of a sounding-board.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9nlr1sFa7wQ

Orlando’s gifts received early recognition, and at the age of 21 he was appointed organist of the Chapel Royal under the service of James I. The pinnacle of his instrumental career was his appointment as organist of Westminster Abbey in 1623. The French ambassador visiting in 1624 reported, “At the entrance, the organ was touched by the best finger of that age, Mr. Orlando Gibbons, and while a verse was played…the choristers sang three several anthems, with most exquisite voices before them.” Gibbons’ religious music was closely tied to his devout Anglican believes. He avoided Latin texts, and as a master of serious polyphonic music his full anthems have attracted particular praise. In addition, his output includes madrigals, motets, verse anthems and consort songs, all crafted with meticulous attention to text setting. Gibbons avoided excessive word painting and instead relied on expressive declamation and powerful rhythmic treatment with short passages of vocal bravura.

Orlando Gibbons suddenly died at the age of 41. Although it was initially suspected that he died of the plague, the post-mortem report details, “…we viewed the body and found it clean without any spots of any contagious matter. In the brain we found the whole & sole cause of his sickness namely a great admirable blackness & syderation in the outside of the brain. Within the brain there did issue out abundance of water intermixed with blood and this we affirm to be the only cause of his sudden death.” Orlando Gibbons left behind his wife Elisabeth and seven children. The orphaned children were placed into the care of his brother Edward Gibbons. And it was Christopher Gibbons, Orlando’s eldest surviving son, who inherited the musical gene from his father. He writes, “I was bred up from a Child to Music under my uncle.” Christopher followed in his father’s footsteps and became a noted organist and composer described as “a great master in the ecclesiastical stile, and also in consort music.”

Christopher Gibbons continued in the musical traditions practiced by his father, with his compositions described as “bold, solid, and strong, but desultory and not without a little of the barbaresque.” In his mature years, Gibbons was well established, and he is mentioned several times in Samuel Pepys’ diaries. His music has only recently been rediscovered, but we might well accord him a substantial role in the rebirth of English music following the English Civil War. In addition, Christopher Gibbons has rightly been credited for nurturing several great Restoration composers, including John Blow and Henry Purcell. If you need yet another example of the saying “the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree,” look no further than the Gibbons family!

By Georg Predota. Republished with permission from Interlude, Hong Kong.