Mahler’s First Symphony: The Titan

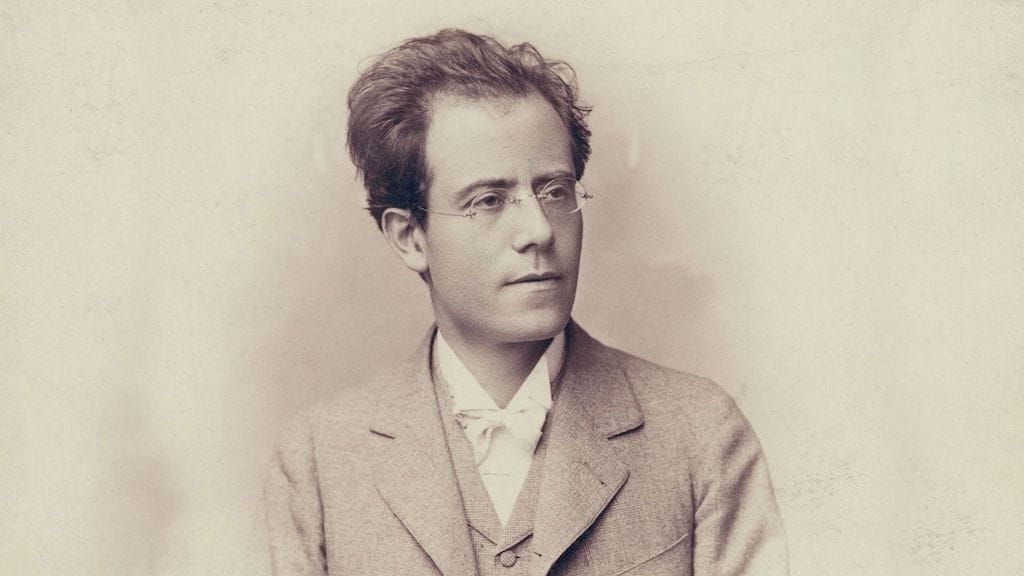

Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 in D Major is music rooted in nature and song. It is the work of a 28-year-old composer who was rapidly rising as one of Europe’s premier conductors, and who was coming out of a stormy love affair with Marion von Weber, the wife of the grandson of composer, Carl Maria von Weber. It is music which synthesizes the Romantic influences of Beethoven, Schubert, Berlioz, Liszt, and Bruckner, while opening the door to something profoundly new. In the First Symphony, Mahler’s cosmic conception of the symphony arrives fully formed. Exalted chorales, military fanfares, and the mundane sounds of a street organ grinder meet in this music filled with irony and mercurial mood shifts. The instruments of the orchestra, each with their distinct personas, come into new focus. At moments, the instruments are pushed out of their comfort zones to achieve what one early critic described as “rough sonorities to exaggerate expressions and sound effects.”

Completed in 1888, the First Symphony was originally conceived as a five-movement tone poem in two sections. Following the unsuccessful premiere in Budapest, one critic derided the work as “a parody of a symphony.” Before a subsequent performance, Mahler supplied a program note with the hope that the music would be better understood. Its poetic allusions included references to spring, the awakening of nature, a funeral march, and the Hero’s journey from a fiery inferno to celestial triumph. The subtitle, Titan, was a reference to a novel by Jean Paul Richter. Soon, Mahler discarded the program and removed the second movement, Blumine. Tighter and more focused, the First Symphony was reborn as a four-movement piece of absolute music.

The first movement is marked, Langsam, schleppend: wie ein Naturlaut (“Slow, dragging: as if spoken by nature”). It begins with a seven octave deep “A” which emerges out of silence. In a foreshadowing of Bartók’s haunting “Night music,” hushed harmonics in the strings evoke the raspy hum of insects. Tentatively, a theme made up of falling fourths takes shape. These opening bars, filled with tension and stasis, simultaneously, revisit and extend the similar opening of Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony. Clarinets intone distant fanfares, which are soon joined by offstage trumpets. Gradually, the animals of the forest awaken. Amid the birdsongs is a cuckoo call which is translated from the usual third to a quirky falling fourth. An ominous chromatic line ascends slowly in the low strings. With the arrival of the movement’s main theme, we emerge into the sunlight. This melody is taken from the second of Mahler’s Songs of a Wayfarer, “Ging heut’ Morgen über’s Feld” (“I Went This Morning over the Field”). The song’s text revels in the beauty of nature, including the dew on the grass and the “bluebells in the field.” In a single, explosive climax, all of the movement’s tension is released. As the Symphony’s introduction outlines (in the composer’s words) “sounds of nature, not music,” this glorious cacophony is pure sound. Exuberant hunting horn calls ring out. The final bars are filled with hearty laughter.

The second movement Kräftig bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell (“With powerful movement, but not too fast”) is an exhilarating scherzo. The joyful rustic dance unfolds as an Austrian Ländler. Filled with an infectious sense of motion, the music is punctuated by occasional raspy stopped horns and col legno, in which bows are slapped vigorously against the strings. The solo horn introduces the charming trio section, and returns us to the Scherzo. In the final bars, the main theme is quickened and compressed, plunging forward with jubilant energy.

Mahler provides an extensive marking for the third movement, Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen —Sehr einfach und schlicht wie eine Volksweise (“Solemn and measured, without dragging —Very simple, like a folk tune”). A funeral march begins on the children’s nursery rhyme round, Frère Jacques, transformed to gloomy minor. It is played by a solitary double bass, accompanied by the timpani. Soon, the melody is passed to other veiled instruments, including the bassoon and tuba. The inspiration for this music was The Huntsman’s Funeral, a popular Austrian children’s engraving in which the animals of the forest are depicted forming a procession to accompany the huntsman’s coffin to the grave. The scene is interrupted, rudely, by the banal “oompah” of a klezmer street band. This collage of musical “scenes”, at once tragic and humorous, left the first audiences confused and deeply disturbed. A celestial respite comes in the movement’s middle section with the final Wayfarer song, Die zwei blauen Augen, emerging in the layered, muted strings.

The First Symphony’s dramatic journey leads unequivocally to the final movement, Stürmisch bewegt — Energisch (“Agitated in storm — Energetic”). As the third movement’s funeral procession fades into the distance, a violent clap of thunder unleashes a hellish inferno. The opening bars are filled with a sense of heroic struggle, amid mortal blows. Mahler quotes a snarling chromatic motif from Liszt’s Dante Symphony. As the movement continues, glimmers of triumph are cut off. The musicologist, Steven Ledbetter, notes that

This finale aims to move from doubt and tragedy to triumph, and it does so first of all through a violent struggle to regain the home key of the symphony, D major, not heard since the first movement. Mahler first does so with an extraordinary theatrical stroke: a violent, gear-wrenching shift from C minor directly to D major in the full orchestra, triple-forte. But this “triumph” has been dishonestly won; it is completely unmotivated, in harmonic terms, too jarring, too unsatisfactory.

Gradually, the Symphony comes full circle, with the return of motivic threads from the first movement. The animals of the forest return, and the ominous motif, first heard in minor in the Symphony’s opening bars, is transformed into a celebratory chorale in D major. Triumphantly, it echoes the “Hallelujah” chorus from Handel’s Messiah. For the final statement of the chorale, Mahler requests that the seven horns stand, so as to “drown everything, even the trumpets.”

This 2021 concert performance features Manfred Honeck and the NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra: