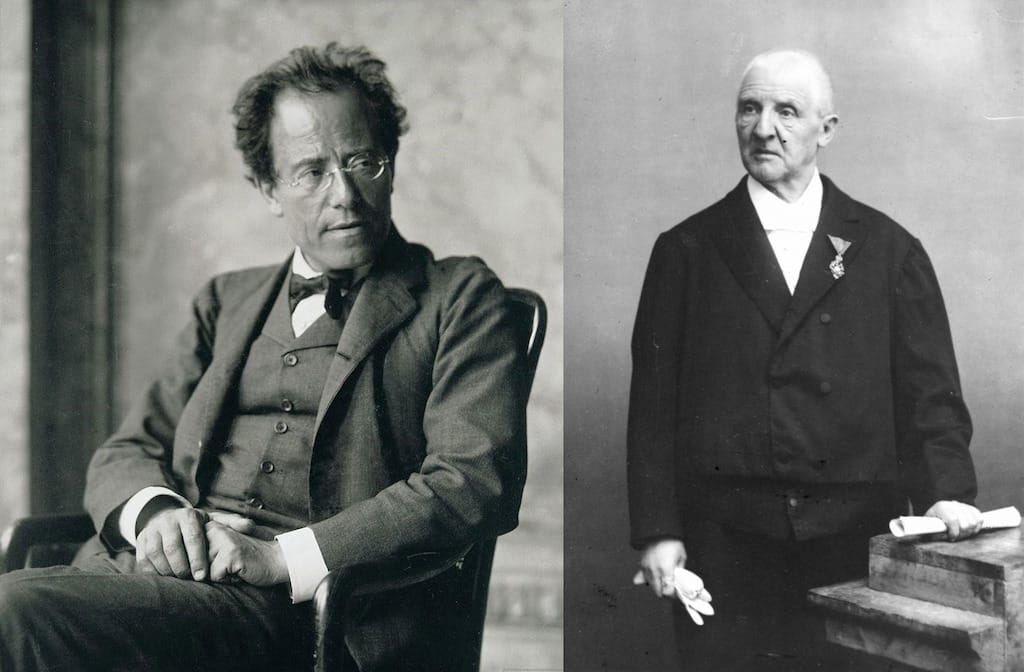

Mahler and Bruckner: The Masters of Melancholy

Through vast symphonies filled with awe and anguish, Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner delved into the human condition, crafting deeply spiritual and psychological works that continue to resonate in an increasingly fragmented world.

In the grand narrative of Western classical music, the symphonic tradition of the Austro-Germanic world occupies a towering place. From Beethoven’s heroic individualism to Brahms’ intellectual rigour, the symphony became a vessel for expressing the most profound emotional and philosophical ideas of its time. Yet, it is in the music of Gustav Mahler and Anton Bruckner that we find an unflinching confrontation with the existential condition of humanity. Their works, often monumental in scale and psychological depth, give voice to the inner struggles of the soul, the loneliness of man in an indifferent cosmos, and the yearning for transcendence.

Though vastly different in personality and musical language, both Mahler and Bruckner are united in their pursuit of a metaphysical truth through sound. They were not merely composers of beautiful music. They were seekers. Their symphonies do not soothe, they provoke. They do not affirm, they question. Through their distinct visions, they each became, in their own way, masters of melancholy.

Anton Bruckner: Devotion, Doubt, and the Infinite

Anton Bruckner, the deeply devout Austrian organist and composer, is often remembered for his religious humility and obsessive self-revision. Born in 1824 in the small village of Ansfelden, Bruckner lived a life defined by contradiction. Though revered by some as a genius in his lifetime, he was also mocked as a country bumpkin and subjected to withering criticism, particularly by supporters of Brahms. Despite this, he persevered, creating symphonies that seem to reach into the very fabric of the cosmos.

Bruckner’s symphonies unfold slowly, almost as acts of devotion. They are architectural in scale and spiritual in ambition. The Fourth, with its subtitle “Romantic”, may offer pastoral imagery and noble horn calls, but the later symphonies speak more deeply to the human condition. The Eighth, for instance, is a towering monument of sound and silence. Its opening tremolo in the strings creates a sense of cosmic awe, like the universe awakening from silence. Themes appear, evolve, and dissolve, much like thoughts in prayer or doubt in the mind of a believer.

Bruckner’s melancholy is not dramatic or theatrical. It is devotional and cosmic. It emerges from the struggle between faith and uncertainty, from the awe before the divine and the silence that sometimes answers back. His adagios, particularly those in the Seventh and Ninth symphonies, are some of the most transcendent and tender expressions in all of symphonic literature. In them, one hears not despair, but resignation, humility, and hope suspended in sorrow.

The Ninth Symphony, left incomplete at his death in 1896, is perhaps the most poignant of all. Dedicated “to the dear Lord”, its final movement was never finished, as though Bruckner could only reach so far before mortality intervened. Even so, the first three movements feel complete in their journey. The listener is left at the edge of eternity, in communion with something vast and unknowable.

Gustav Mahler: Fractured Modernity and the Inner Self

Where Bruckner was contemplative and cosmic, Gustav Mahler was neurotic and intensely psychological. Born in 1860 in what is now the Czech Republic, Mahler was a child of contradictions. A Jew in an anti-Semitic empire, a Bohemian in a German-speaking cultural elite, and a conductor who struggled for artistic freedom, Mahler channelled his inner turmoil into music that is nothing short of existential autobiography.

Mahler’s symphonies are labyrinths of feeling. They draw upon folk songs, military marches, funeral processions, and heavenly choirs. They juxtapose the banal with the sublime, the grotesque with the sacred. He famously said, “A symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything.” In doing so, his music becomes a mirror for the fragmented consciousness of the modern man.

Take the First Symphony, often nicknamed the “Titan”. Its third movement, a funeral march based on “Frère Jacques” in a minor key, is at once tragic and ironic. The juxtaposition of a children’s song with the weight of death reflects Mahler’s fascination with innocence lost, a recurring theme throughout his work. The Fifth Symphony’s opening funeral march plunges us directly into grief, while the Adagietto of the same work offers a moment of aching beauty, interpreted by many as a love letter to his wife Alma.

Yet it is in the Sixth Symphony, often called the “Tragic”, that Mahler confronts fate most starkly. The work ends not in triumph but in crushing defeat, with hammer blows that symbolise fate itself, striking down the protagonist. It is a rare example in symphonic literature of complete despair, a musical admission that not all suffering can be transcended.

Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, completed just before his death in 1911, is arguably his most profound meditation on mortality. The final movement, a slow farewell, seems to dissolve into silence. It is not dramatic but unbearably intimate. As the music fades, one is left with the sense of a soul departing, not in anguish, but in acceptance. Leonard Bernstein called it “a sonic farewell to life itself”.

Different Paths to the Same Abyss

Despite their different temperaments, Mahler and Bruckner were kindred spirits in their obsession with the metaphysical. They lived in a time of cultural crisis, when religion was losing its unquestioned authority, and science, psychology, and nihilism were on the rise. Each man, in his own way, responded by constructing symphonies not just as musical works, but as spiritual journeys.

Bruckner clung to the Church, to God, to the eternal. His symphonies are cathedrals of sound, filled with organ-like sonorities and vast, reverent spaces. The melancholy in his music comes not from despair, but from awe, from the struggle to maintain belief in the face of doubt.

Mahler, on the other hand, embraced the chaos of the modern world. His music contains irony, anxiety, contradiction. He was not trying to confirm faith, but to wrestle with its absence. For Mahler, melancholy is the expression of a fractured inner world, a psychological wound, a consciousness aware of its own demise.

It is no coincidence that Mahler was deeply influenced by Freud, while Bruckner was steeped in plainchant and church modes. One turned inward, the other upward. One questioned, the other prayed. Yet both arrived at works that ask us to consider our place in the universe, our confrontation with death, and the fragile beauty of existence.

Legacy and Modern Resonance

In the twenty-first century, the music of Mahler and Bruckner continues to resonate with audiences around the world. Perhaps this is because their works speak to perennial concerns. In an age where mental health, spiritual emptiness, and existential uncertainty are part of the cultural conversation, their symphonies offer not answers, but empathy.

Bruckner’s slow unfolding harmonies give space for contemplation in a world that often moves too fast. Mahler’s emotional honesty, his refusal to look away from the terror and absurdity of life, feels more relevant than ever.

Their music is not easy. It demands time, attention, and emotional engagement. But for those willing to listen, it opens a portal to a deeper understanding of what it means to be human.

To call Mahler and Bruckner the “masters of melancholy” is not to reduce their work to sadness. Rather, it is to acknowledge that their music explores the full range of human emotion, including those feelings society often seeks to suppress. They remind us that melancholy is not weakness, but wisdom. It is the knowledge that life is fleeting, that suffering is real, and that beauty often emerges through pain.