Magical Midori: From Prodigy to Legend

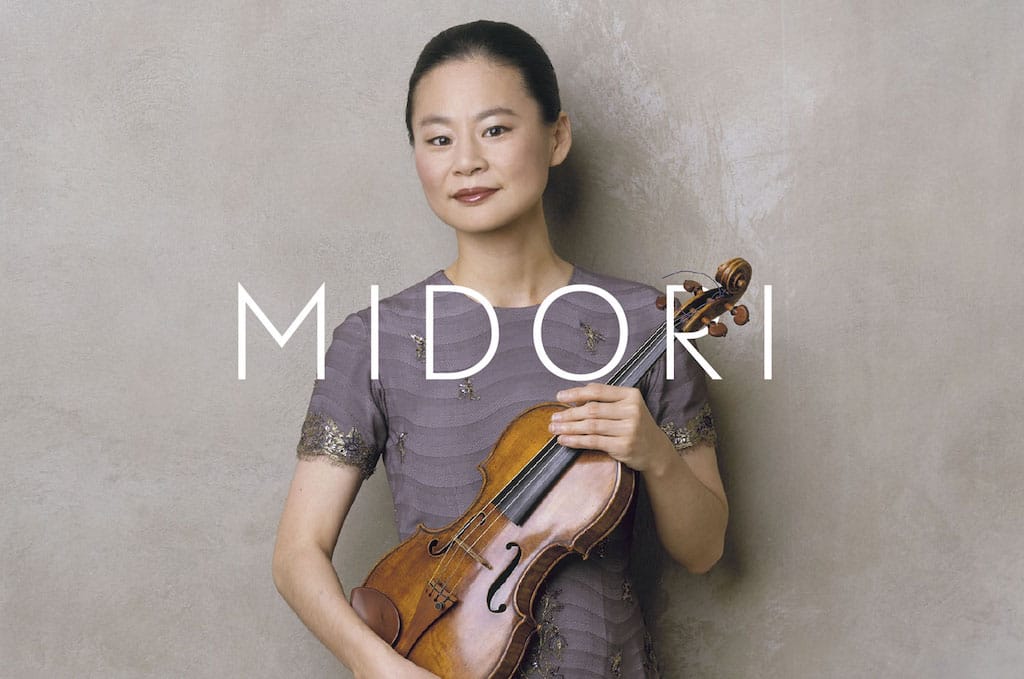

From child prodigy to international legend, Midori’s violin mastery has captivated audiences for decades. Her performances blend technical brilliance with profound emotion, making her one of classical music’s most revered and enduring virtuosos.

Despite the constant emergence of new virtuoso violin ‘superstars’ from all over the world in western classical music, Midori, now 53, still stands out.

She was the epitome of the “child prodigy”, a term sadly too loosely used nowadays for much lesser ability. At age six(!), she performed all the Paganini caprices and the J.S. Bach Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin.

She made her debut with the New York Philharmonic under the baton of Maestro Zubin Mehta at age 11 as a surprise guest soloist at the New Year's Eve Gala in 1982. The rest of her career since then is the stuff of legend and music history.

During my UK decade, I heard her just once, at the 2002 BBC Proms festival, when she played Samuel Barber’s lyrical Violin Concerto with the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Christoph Eschenbach.

But I hadn’t heard her in a more intimate, recital setting. This is why when I learned she would be playing in 2019 with pianist Ieva Jokubaviciute at the Tata Theatre, National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) Mumbai, I made a dedicated trip to the big bad city just to hear her. The duo also performed a day before this in Pune under the auspices of the Poona Musical Society.

At the risk of being repetitive (as I’ve said this so often), I think it both a scandal and a travesty that for decade after frustrating decade, Goa, despite such a centuries-old heritage of exposure to western music, continues to let itself be bypassed on the tour schedules of the world’s greatest exponents of western classical music, even though they come so tantalisingly close. The result is that generation after generation of our youth is growing up, quite literally not knowing what they are missing. Yet adult Goa has the wherewithal to bring mega-expensive drug-fuelled ‘festivals’ like Sunburn, overriding popular opposition (and it is rumoured at least one politician of the ruling establishment lines his pockets in crores for ‘facilitating the extravaganza), but not for wholesome soul-nourishing western classical music at a minuscule fraction of the cost. Instead, the Goan populace is lulled into slumber fed on wolves’ milk and numbed by utter rubbish about musical ‘Renaissance’ when anyone who truly has discerning ears to hear and listen, knows it is sheer mediocrity on offer instead. Such hyperbole (whether ignorant or devious) praising any drivel as long as highlights caste peers deprives a first-generation listener and readership of any sense of perspective and proportion, because they have nothing else (apart from the wealth on the internet, of course) to compare it as yardstick with in terms of live concert performance. Ignorance is bliss.

Even more tragicomic is the “cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face” syndrome. Catholic elite Goa would rather deprive their own children of opportunities to unearth, nurture and bring their musical potential to fruition than support someone not of their own caste location who earnestly wants to do this. Far better (so goes their warped ‘logic’) to be in petty charge of shallow mediocrity than to risk relinquishing control. This mad obsession with “calling the shots” and constantly wanting to be in the limelight take precedence over caring for their own offspring’s holistic creative development; such is the absurdity that caste prejudice engenders.

Midori returned late last month (with brilliant Turkish-American pianist Özgür Aydin) to South Asia; this time her tour circuit embraced not just Mumbai (hosted by the Mehli Mehta Music Foundation as part of its Zubin Mehta Celebrity Concert series, a nod no doubt to her career debut) and Pune but also Colombo, Sri Lanka. Goa slumbers on in blissful ignorance. I made another trip to hear her in Mumbai.

Midori’s 2019 concert programme could be broadly described as a French pot-pourri (Claude Debussy-Hartmann: Girl with Flaxen Hair; Gabriel Fauré: Sonata No.1 in A Major, Op.13; Fauré: Les berceaux, Op. 23/1 and Debussy: Sonata in G minor, L140) with a generous helping of Johannes Brahms (the whirlwind Sonatensatz: Scherzo from FAE Sonata and his mighty Sonata No.3 in D minor, Op.108).

In her 2024 programme, she began with Brahms’s friend, confidante and muse Clara Schumann (1819- 1896). Her Three Romances for Violin and Piano, Opus 22 (1853, significantly, the year Brahms entered the Schumann’s lives) written for her husband Robert’s birthday and dedicated to mutual friend violinist joseph Joachim, eloquently display her own genius at composition, which she sadly sublimated in deference to her husband’s career as a composer and the prevailing notion then that women “could not” be genuinely creative.

It whetted the appetite for Brahms’s Violin Sonata No. 1 in G major, Op. 78. Although many in the audience awaited the pyrotechnics of the second half, this was for me, the “main course”, what I had largely come to hear. It is essentially a sonata for violin and piano. Calling the pianist an ‘accompanist’ doesn’t do the role justice; the term ‘collaborative pianist’ is now thought more appropriate.

There is another connection with Clara Schumann; Brahms wrote this sonata in 1879m after the untimely death of the Schumann’s son (and Brahms’s godson), violinist-poet Felix at 24. Fragmentary references in the first and last movements to two of Brahms’s earlier songs, Regenlied and Nachklang op.59, No.3 and 4, respectively, (set to poems by his friend Klaus Groth) of 1873, which both evoke rain, have earned it the nickname ‘Regensonate’ (Rain sonata).

A Midori concert is a sublime experience; she not only plays the music, but she also ‘becomes’ the music, getting to its soul with every fibre of her being, and communicates it to the listener in the most profound way.

Brahms’s chamber works for piano make huge technical and expressive demands on the instrument, and Aydin was a sensitive yet flexible partner, (here and throughout the concert) ever present but never in the way.

The second half was decidedly French, beginning with Francis Poulenc’s Sonata for Violin and Piano, FP 119. Poulenc apparently did "not like the violin in the singular" and only wrote this sonata at the insistence of violinist Ginette Neveu, who premiered it with Poulenc as pianist. It is another ‘tribute’ piece, composed (1942-43) in memory of Spanish poet Federico García Lorca (1898-1936). Although Poulenc (and many early critics) were dissatisfied with it, it conjures up a sound-world with uniquely Poulenc-ian harmonies, and several quotes from his and others’ works. I detected a snippet from Bizet’s Carmen in the first movement, no doubt for its ‘Spanish’ flavour.

Midori-Aydin ended with Maurice Ravel; first ‘Kaddish’ from Deux mélodies hébraïques ("Two Hebrew Songs"), a heartfelt Jewish ‘Song of the Dead’ that through the universal language of music ‘speaks’ to everyone. As I listened, Gaza was foremost in my mind.

The final work (for which Midori set aside the music-stand and played from memory was the show-stopper, Ravel’s ‘Tzigane’ (Gypsy), in his words "a virtuoso piece in the style of a Hungarian rhapsody". Writing in her own program notes for Tzigane, the Cadenza section “demands a particular blend of spontaneity, uniqueness, and coordination… it is as if the performer must completely redefine violin playing!”

Midori did all of that and more that enchanted evening.

This article first appeared in The Navhind Times, Goa, India.