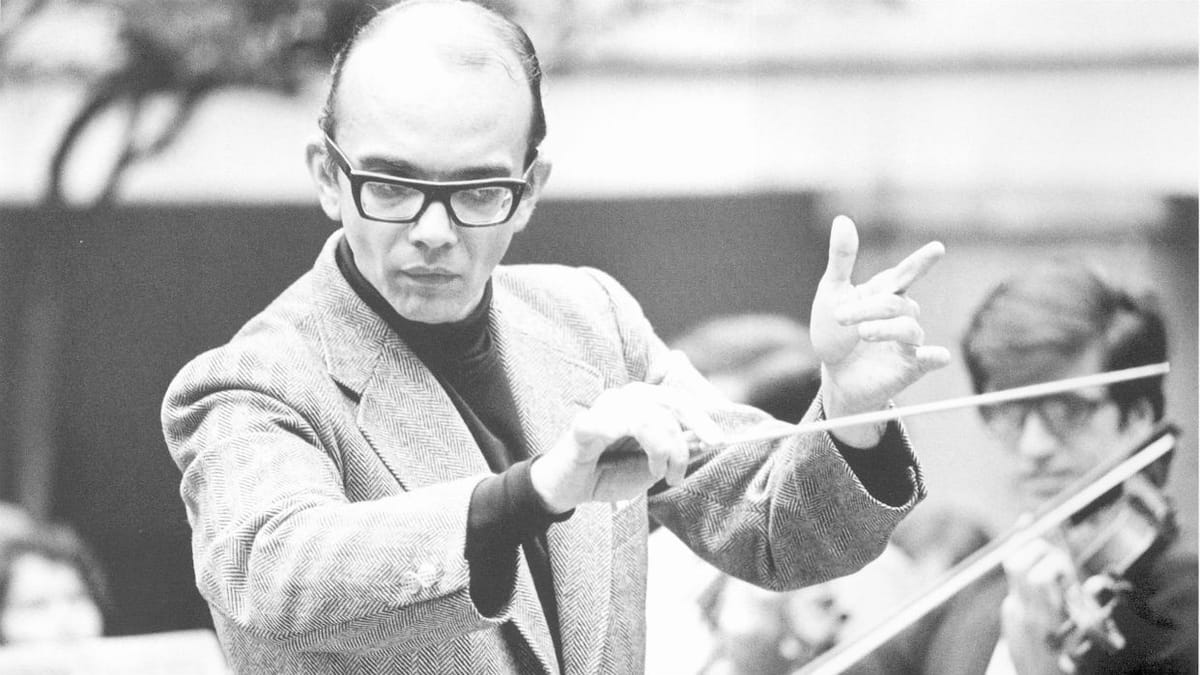

Maestro José António Abreu (1939-2018)

“From the minute a child is taught how to play an instrument, he’s no longer poor”

Many years ago, soon after we had set up Child’s Play India Foundation, a music charity inspired hugely by the phenomenal success of Venezuela’s El Sistema movement, a wealthy Bombay socialite engaged me in conversation about its founder, Venezuelan conductor, pianist, economist, educator, activist and politician José António Abreu. “He’s a Catholic priest, of course. Didn’t you know? I’m surprised!” she exclaimed patronisingly. It was pointless arguing further. The rich don’t let petty irritants like facts stop them from spouting.

But she could be forgiven for her assumption, as Abreu did cut a priestly figure, in the way his children and colleagues revered him, his quiet wisdom, and his unflinching “faith in a divine force that impels the human spirit to aspire to higher things.”

Until 2007, I was blissfully unaware of the existence of this great man, when my own “road to Damascus” moment took me on the path to music education as an agency for social change. I was in England, well on the way to living out my years there as General Practitioner on the National Health Service, when a casual whimsical conversation with my wife put paid to that. I’m still not sure how it began, but it must have been many things: the formation of a professional, salaried, high-calibre symphony orchestra in Mumbai, but with only a fraction of its composition Indian; and perhaps also an item in the news about street-kids being given disposable cameras, and the breathtaking pictures that resulted from their own perspective of their surroundings.

“Wouldn’t it be wonderful,” I thought aloud, “if India’s disadvantaged children in our slums and elsewhere could be given orchestral instruments, and the best possible instruction in how to play them? Would we have world-class orchestras in every village, town and city?”

Some months later, at the BBC Proms music festival at London’s Royal Albert Hall, it seemed as if the Universe had conspired, to bring centre-stage for the first time, not just one, but two orchestras from two different corners of the globe made up of disadvantaged youth playing to a world-class level: the Soweto Buskaid String Ensemble, Johannesburg, South Africa; and the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra, Venezuela. Those concerts changed my life.

Less than a year after those jaw-dropping concerts, we had relocated back to Goa to set up Child’s Play. Inevitably, on this almost spiritual journey, I encountered again and again, the writings, speeches and philosophy of José António Abreu. Over time, I would meet many others who also were at the Venezuelan Proms concert, and underwent a similar transformation, going back to their roots to establish music education projects tied to social empowerment.

How did a summa cum laude economics graduate trigger such a worldwide music revolution whose benevolent aftershocks are still touching millions of lives everywhere?

A profound love of music, beyond doubt: after initial music instruction in Barquisimeto, he studied piano, organ, harpsichord and composition at the Caracas Musical Declamation Academy.

In his 2009 TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) talk, Abreu explained: “Since my early childhood, I always wanted to be a musician.” He thanked God for having the necessary community support to become one. But that was not enough for him: it became his lifelong dream that every Venezuelan child should have that same opportunity.

In 1975, he arrived at the first rehearsal in an underground parking garage with great optimism: he had received a donation of 50 music stands, and so could accommodate 100 children. But only eleven children turned up.

So he asked himself: “Do I close the programme, or multiply these kids?” At that instant, he made his decision. He told those eleven children that he would turn them into “one of the leading orchestras in the world.”

And so it came to pass. At the TED talk, Abreu quoted the London Times music critic who in 2009, said that if there ever were on Orchestra World Cup, Venezuela’s Youth Orchestra would be among the top five.

Shattering the illusion that art was the monopoly of the elite was a strong driving force. Abreu believed that art was “a social right, a right for all people.”

“In its essence, the orchestra and choir are much more than artistic structures. They are examples and schools of social life, because to sing and play together means to intimately coexist toward perfection and excellence, following a strict discipline of organisation and co-ordination in order to seek the harmonic interdependence of voices and instruments. That’s how they build a spirit of solidarity and fraternity among them, develop their self-esteem, and foster the ethical and aesthetical values related to the music in all its senses.”

“This is why music is important in the awakening of sensibility, in the forging of values and in the training of youngsters to teach other kids.”

Two shining products of El Sistema (short for FESNOJIV, or Fundación del Estado para el Sistema Nacional de las Orquestas Juveniles e Infantiles de Venezuela) are Edicson Ruíz, today double-bassist in the Berlin Philharmonic, and even more iconic, Gustavo Dudamel, today musical director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, but still overall leader of Venezuela’s junior orchestras.

Abreu called El Sistema “a programme of social rescue and deep cultural transformation.. with no distinctions whatsoever, but emphasizing the vulnerable and endangered social groups.” Its impact was felt in “three fundamental circles: personal/social; family; and community.”

“From the minute a child is taught how to play an instrument, he’s no longer poor. He becomes a child in progress heading for a professional level, who’ll become a full citizen.” To Abreu, music was the “numero uno” prevention against all social ills.

It was my own dream to someday make a pilgrimage to Venezuela’s El Sistema and meet the great man himself. That was not to be; he passed away on 24 March at 78, and was accorded a ceremonial funeral the next day. But I have seen how his legacy lives on, in Scotland, England and the US, in projects he inspired. And when we at Child’s Play encounter our own setbacks, we too ask ourselves: “Do I close the programme, or multiply these kids?” And we draw inspiration from Abreu when we vow to do the latter. We’re organising Goa’s first ever children’s orchestra and choir summer camp (open to all) at Don Bosco Oratory Panjim, starting tomorrow. One day, our Child’s Play’s children will also be among the leading orchestras and choirs in the world.

Rest in peace, Maestro!

This article first appeared in The Navhind Times