Lydian Nadhaswaram’s Bumblebee

“Ladies and gentlemen, today I will be playing The Flight of the Bumblebee.”

With these words, uttered with a charm that made the audience smile and give a round of applause before a single note had been played, Lydian Nadhaswaram launched into his rendition of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s intricate composition. This was his first appearance in ”The World’s Best,” a talent competition on the US television channel CBS. To advance, the performer had to impress not only a panel of three prominent American judges (Drew Barrymore, Faith Hill, and RuPaul Charles) but also fifty experts drawn from every field of arts and entertainment from countries across the world.

The Flight of the Bumblebee musically depicts a bumblebee’s apparently chaotic and swiftly changing flying pattern. At first glance it would seem that a bumblebee should not be able to fly; its wings are too frail to keep its bulky body aloft. But bees fly by swiftly rotating their wings. This creates pockets of low air pressure, which give rise to small currents above the bee’s wings, hoist it into the air and keep it airborne. The wing rotation and air motion results in buzzing and whirring sounds, which Rimsky-Korsakov mimics through his music.

The pace of the music is frenetic, crammed with nearly uninterrupted runs of chromaticsixteenth notes. What challenges musicians (more than the pitch or the range of notes) is their ability to move from one note to the next quickly enough to sustain the tempo. This complexity calls for considerable skills from the musician; the piece is considered notoriously hard to play. So when Lydian finished his recital with panache, the applause was thunderous.

But none of them had any inkling about what was coming next.

Lydian had played the piece in the vivace tempo, at 160 beats per minute (bpm), which is about the pace it is usually performed. The highest tempo is prestissimo, which is anything over 200 bpm. Most pianists get jittery the closer they approach this degree of pace, but Lydian played the piece the second time at 208 bpm without appearing the least fazed, and the astonishment on the faces of some of the judges captured on camera and their exclamations of surprise said it all.

But Lydian wasn’t done. In his finale, he played the piece at an electrifying 325 bpm (twice its conventional tempo) while keeping the music still recognisable instead of reducing it into a cacophony. Prestissimo does not describe this music display adequately; the speed was beyond terminology.

Lydian Nadhaswaram performs The Flight of the Bumblebee in three tempos

James Corden, the show’s host, told Lydian onstage: “You blew everyone in this room away. You should be so proud.” He also offered high praise on Twitter: “This is genuinely one of the best things I’ve ever seen live.”

This is genuinely one of the best things I’ve ever seen live. https://t.co/FY5LH6vxfI

— James Corden (@JKCorden) February 8, 2019

However, not all comments were honeyed. One of the American judges said: “There is no doubt you are the fastest player in the world but I would love to feel what you were playing.” This sentiment was echoed by one of the international judges.

Music and Feeling

Music draws its power from the emotions it evokes in the listener, and these vary with the composition. Rossini’s “William Tell Overture,” Pachelbel’s “Canon in D Major,” and Ravel’s “Boléro” draw out very different feelings from within us.

Lydian and his sister Amirthavarshini, fine young musicians that they are, are well aware of the inseparable bond between music and the emotions. Lydian often says that playing the piano makes him happy. Amirthavarshini spoke about how musicians have the good fortune of expressing deep feelings through music.

Over the years, Lydian has been rapidly evolving as a musician and is remarkably accomplished for one so young. Augustine Paul, director of the Madras Musical Association and Lydian’s piano teacher, said this to me a couple of years back: “Lydian’s head is full of musical knowledge. It’s very difficult to impart certain things to students but he has imbibed those by himself. He doesn’t need instruction on how to do it – he has figured it himself. The sheet music is in front of us. We see the same notes. The tune is the same. But the way you play it makes the difference. A child will play it flat, without any colour. But the shape of Lydian’s phrases are not of his age. The way he interprets a piece is much above what a child of ten can do. He is able to feel it. And it comes to him naturally.”

Perhaps the judges who made the comments were hearing Lydian for the first time and were giving him well-meaning general advice about the importance of playing with feeling. Or perhaps they were referring to his specific performance that day ─ so let us take a closer look at what emotions Rimsky-Korsakov’s composition might evoke.

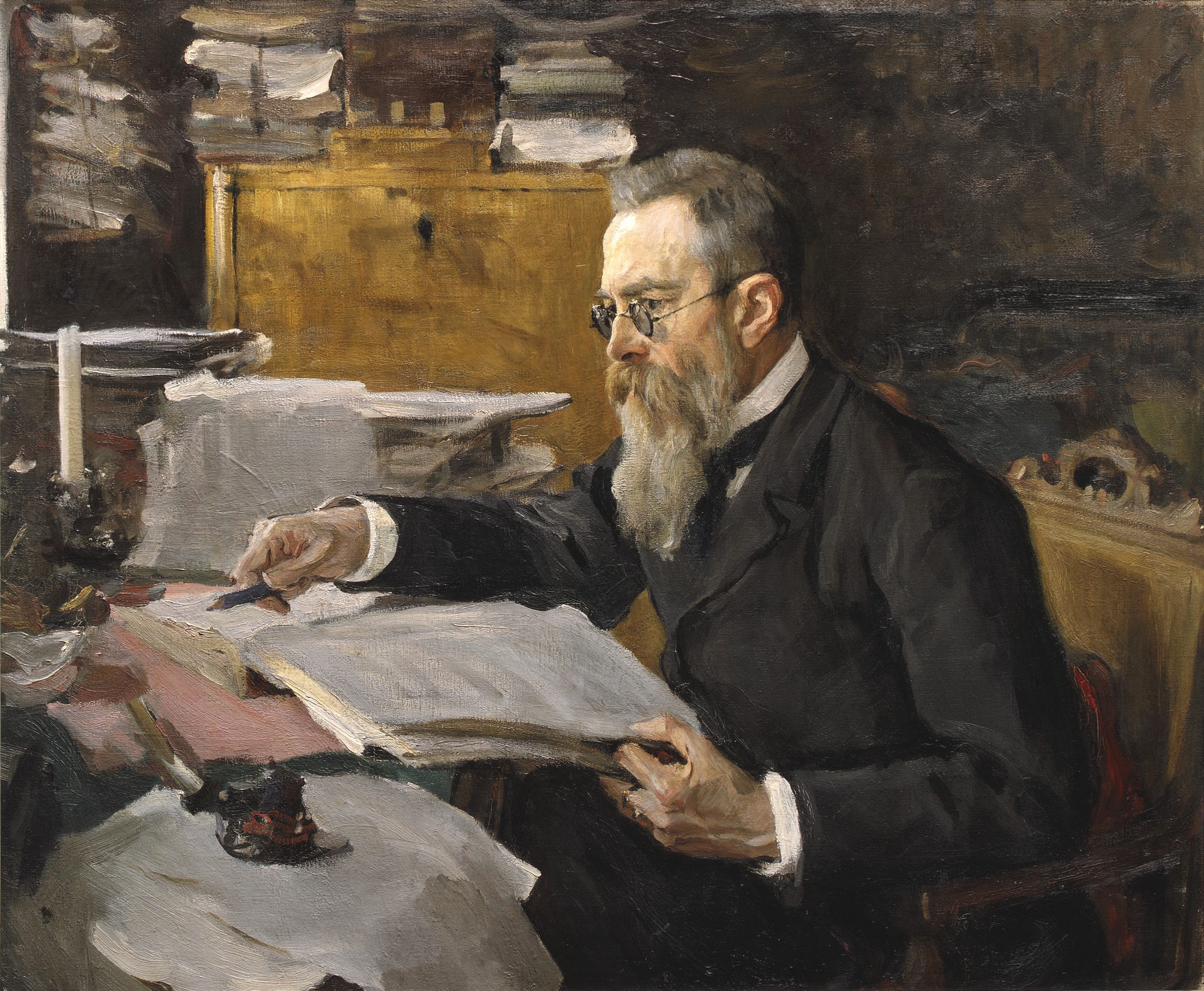

Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera: Tsar Saltan

Aleksandr Pushkin, who many consider to be Russia’s finest poet and the founder of modern Russian literature, wrote a fairytale poem, The Tale of Tsar Saltán. To celebrate Pushkin’s centenary in 1900, the poem was turned into an opera with composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov providing the music to the libretto by Vladimir Belsky. The tsar’s son Gvidón is born while the tsar is away at war, and his two wicked aunts toss him and his mother into the sea. They are washed ashore on an island. A magic swan helps Gvidón get back to his father by turning him into a bumblebee and asking him to fly to a passing ship bound to his father’s kingdom and travel as a stowaway. The swan sings:

Well, now, my bumblebee, go on a spree,

Catch up with the ship on the sea,

Go down secretly,

Get deep into a crack.

Good luck, Gvidón – fly!

The bumblebee takes off in a frantic effort to reach the ship, to the music of The Flight of the Bumblebee.

The video below, a promotional by Mariinsky, provides glimpses of the opera. Mariinsky is the historic opera theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, where many masterworks of Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, and Rimsky-Korsakov premiered. This version of The Tale of Tsar Saltan is a lavish production. The video uses The Flight of the Bumblebee for much of its background music but the visuals are taken from various sections of the opera. We do see the bumblebee in the video: once after the swan has transformed the prince into the bee, and again when the bee wreaks havoc at the tsar’s court.

Glimpses from the opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan (Mariinsky Theatre, Russia)

What, then, is the emotion Rimsky-Korsakov wants us to feel through the music? Surely it is desperation. The bumblebee needs to reach the ship before it gets too far out into the sea. Can it make it before its tiny wings get too tired?

But any piece of art is open to audience interpretation. It is reasonable to assume that the majority of listeners will be unfamiliar with the opera storyline and interpret the piece from their (and not the bee’s) point of view. For instance, as the volume and speed of the music rise (the bee is getting closer) or fall (the bee is moving away), we feel alarm alternating with relief. If we transpose these feelings into the context of the opera, we can visualise the bumblebee get closer to the ship (the music gets fainter) and then struggle as the sea breeze pushes it back to the shore (the music gets louder).

Changes in the score

To add to the challenge of the interpretation, the music itself has undergone some changes in the 118 years after its composition. The original music was composed for strings, with flutes and clarinets chipping in. The continuous runs of chromatic sixteenth notes was passed on from one instrument (or set of instruments) to others in tandem. The score’s tempo was slower; the opera version is about 3 minutes 45 seconds. Perhaps this was a nod to reality: a bumblebee can only fly so fast. Or more to the point, actors had to move around the stage to keep the bumblebee in motion and a fast tempo risked their tripping and falling flat on their faces. In the years since, more instruments (brass and other woodwind instruments) are often added to the orchestra, and the pace has quickened.

Orchestral version of The Flight of the Bumblebee; Berlin Philharmonic, Zubin Mehta conducting.

Moreover, the piece has been arranged for solo performance on several instruments. Sergei Rachmaninoff arranged it for piano; it is this version that Lydian plays. It can be played in under two minutes.

Lydian flies high with the Bumblebee

Several years back when Lydian was enrolled in tabla class in a music school, he heard a student in the piano studio practicing The Flight of the Bumblebee. The beginner played it haltingly, and Lydian was able to memorise the tune. From YouTube he learnt that it was a much faster piece. Within a couple of days, he was playing it presto (at 180 bpm).

Lydian Nadhaswaram playing The Flight of the Bumblebee at age 9, at 200 bpm in a 2/4 time signature

In 2016, at age 10, he became the youngest pianist to be invited to perform for the Mumbai Piano Day at the NCPA Tata Theatre. The last component of his recital was The Flight of the Bumblebee (8:10 onwards).

Lydian Nadhaswaram: The Flight of the Bumblebee, Mumbai Piano Day 2016

Now 13 years old and performing in The World’s Best, Lydian played it at a speed of 325 bpm ─ a remarkable display of technical mastery of the piano. “It’s a tough piece to play at any speed,” Lydian says, adding: “The right hand has to keep playing nonstop.” And one viewer of his performance tweeted: “As a former flautist, I don’t think I could even play a recognizable scale at that speed. As my teacher used to say, I was all musicianship, no technique.”

Quite apart from Lydian’s command over tempo and rhythm, in the first recital we hear the variations in the notes, pacing, and volume. A piece of music is not made out of notes alone – it is also shapes and patterns. The crescendos of Lydian’s second and third recitals heighten our sense of the bee’s desperation. Lydian Nadhaswaram captured the spirit of Rimsky-Korsakov’s composition quite well.