Linda Hedlund and the Revival of Finland’s Forgotten Violin Concertos

Violinist Linda Hedlund discusses musical archaeology, interpretative responsibility, and reviving forgotten Finnish concertos, revealing how archival rediscovery, orchestral listening, and historically informed performance shape her latest Naxos recording.

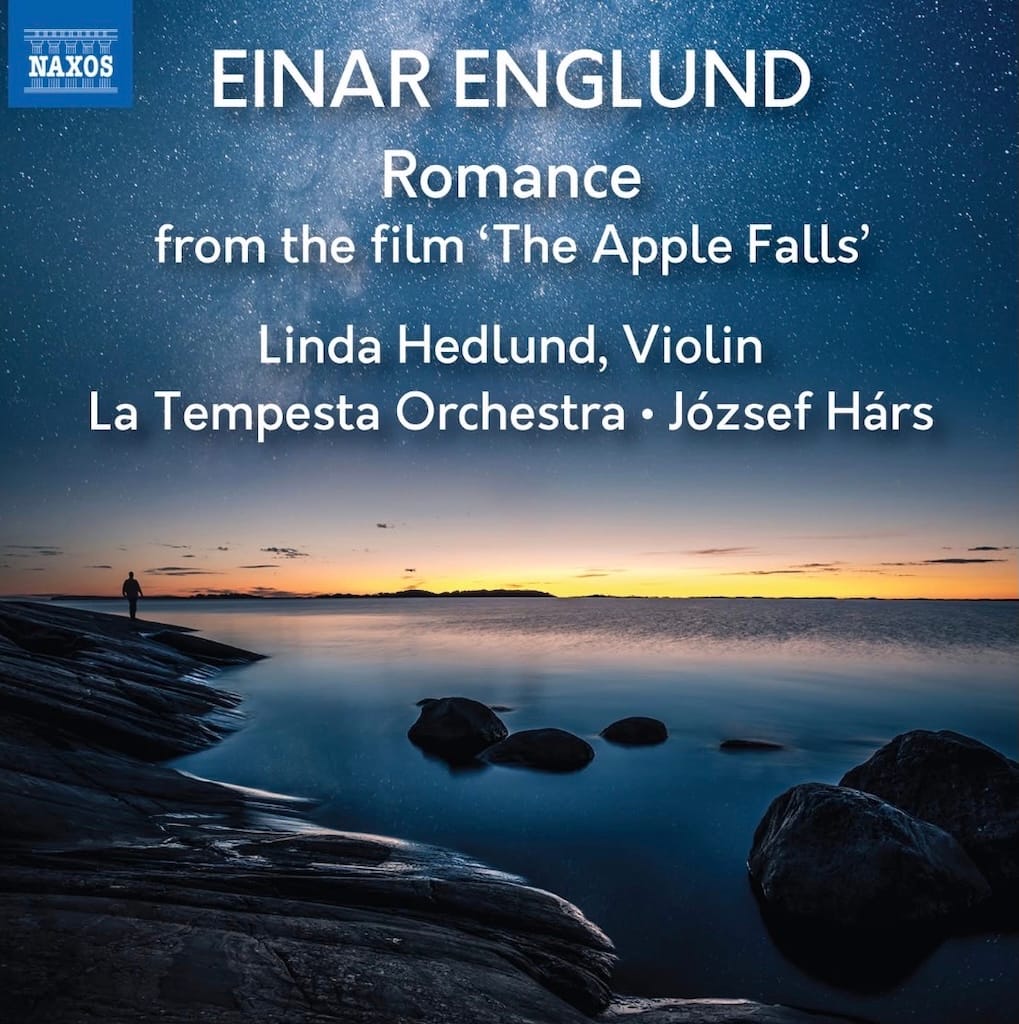

For violinist Linda Hedlund, rediscovery is not a side project but a central artistic impulse. Her new Naxos recording turns the spotlight on Finnish violin concertante works that once resonated in concert halls before quietly slipping from view. Spanning national romanticism, early modernism, and post-war lyricism, the album brings together music by Väinö Raitio, Aarre Merikanto, Selim Palmgren, Väinö Haapalainen, Einar Englund, and Nils-Erik Fougstedt, composers whose voices shaped Finland’s musical identity in complex and often overlooked ways.

Drawing on her wide-ranging career as soloist, concertmaster, baroque specialist, and artistic director of the Emäsalo Music Festival, Hedlund approaches this repertoire not as historical reconstruction but as living music. Working closely with producer Olli-Pekka Tuomisalo, she treats the archive as a place of continuity rather than nostalgia, allowing forgotten scores to speak again with clarity, colour, and urgency. In this conversation, Hedlund reflects on musical archaeology, interpretative responsibility, and why reviving neglected repertoire remains vital to the future of classical music.

Nikhil Sardana: Your new album feels less like a conventional recital disc and more like an act of musical archaeology. What first compelled you to devote an entire recording to Finnish violin concertante works that had slipped so thoroughly out of view?

Linda Hedlund: This is my second album with Naxos. The first one, Evening Dusk Serenade (2021), was critically acclaimed and presented premiere recordings of music by, among others, the Finnish composer George de Godzinsky. When I was searching the archives at that time together with my colleague Dr Olli-Pekka Tuomisalo, who is also the producer of this new album, it became clear that there is in fact a great deal of high-quality music for violin and orchestra that has simply not been performed or recorded yet.

So the project gradually became less about championing curiosities and more about restoring context. In that sense, it really does feel like musical archaeology—not dusting off relics, but reconstructing a landscape and asking listeners to hear it with fresh ears.

NS: Many of the composers represented here were writing at moments of stylistic transition. How do you approach repertoire that resists easy categorisation?

LH: I try to begin with the material itself—the harmonic language, the rhetorical writing, and how the orchestra breathes with the violin—rather than forcing the music into a stylistic category. The score has to dictate the interpretation. Labels can sometimes flatten what is actually happening in the music, whereas the notation itself often tells you exactly how it wants to speak.

NS: Raitio’s Legenda was once widely performed and then disappeared for more than eighty years. When you first encountered it, did it feel like a historical rediscovery, or did it immediately strike you as a living piece?

LH: The works by Väinö Raitio on this album are probably my favourites. I was working from the original handwritten material, which immediately creates a very different relationship with the piece. Jozsef Hars, the conductor, has studied Raitio’s music in great depth and has also made transcriptions of some of his works that are far more practical to work with today.

There was certainly a strong sense of uncovering something lost, but the aim was never to present Legenda as a curiosity. It felt more like reintroducing a voice that had been silent for too long, but still had plenty to say.

NS: You’ve worked extensively as a concertmaster and orchestral musician. How has that experience shaped your approach to concertante repertoire as a soloist?

LH: That orchestral awareness encourages a certain humility. I don’t experience the orchestra as a backdrop, and I don’t try to float above it. For me, it is about listening from within the orchestra, even when you are the soloist.

NS: You are equally active in modern violin repertoire and historically informed baroque performance. Do these two worlds influence each other in your playing?

LH: Very much so. Studying historically informed performance deepens your understanding of where music comes from and gives you more interpretative tools, even for later repertoire. The principles that come from baroque performance do not simply disappear with later styles; they evolve. That awareness of rhetoric, articulation, and musical speech continues to inform how I approach more modern works.

NS: As both a performer and a festival artistic director, you are used to thinking in terms of programme architecture. Did that curatorial mindset influence how you conceived this album?

LH: An album is, in many ways, also a curated space. When you present lesser-known music, there is a responsibility involved because you are often shaping a listener’s first impression. The order of the pieces matters, just as it does in a festival concert. You have to create a context in which the music unfolds organically, taking into account contrasts and affinities, while also bearing in mind the historical background of each work.

NS: Some of the works on this album have no established performance tradition at all. Does that place a different responsibility on you as an interpreter?

LH: Yes, definitely. When you perform this kind of repertoire, there is no existing framework to lean on. All you have is the score, and that has to be your primary guide. I feel a responsibility not only towards the composer, but also towards the listener and perhaps even towards the future of the piece.

My interpretation is not a definitive version. But if it encourages others to take up the work and hear it differently in the future, then I feel my task has been fulfilled.

NS: You’ve spoken of this recording as a revival and an invitation. Do you see this kind of rediscovery as an ongoing part of your artistic path?

LH: Yes. In fact, I already have the repertoire for the next album carved out. That said, I want to let this one have its own space before moving on to the next project.