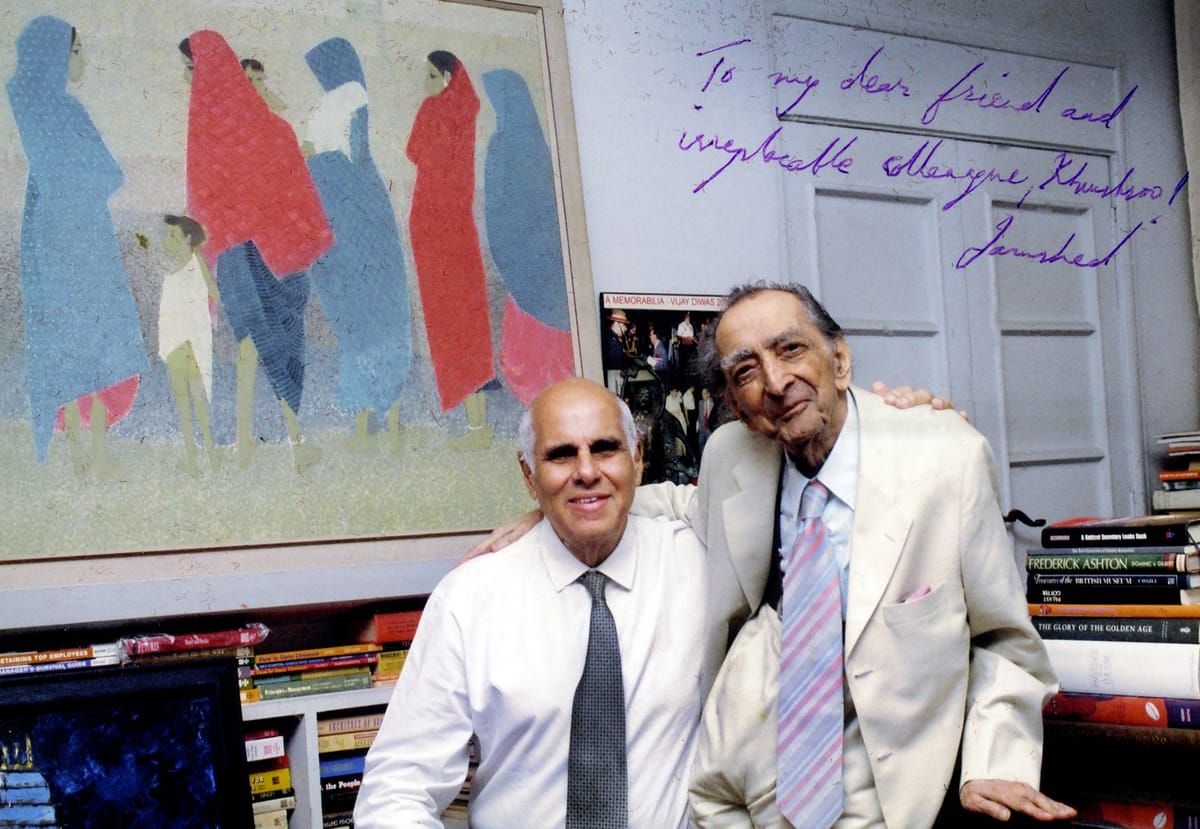

K N Suntook, Chairman – National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai

Nikhil Sardana: Please share you background with us.

K N Suntook: I am a Bombay person. My family has been here for hundreds of years. We grew up in a very western atmosphere. My grandfather had a huge collection of records and would play the piano and sing Lieder after dinner. When my parents visited him, I used to play the gramophone while they chatted and otherwise listened to the running commentary of a match in England. I am very fond of Wagner and vocalists. Fortunately, Zubin Mehta was a friend and I used to go to his house quite often.

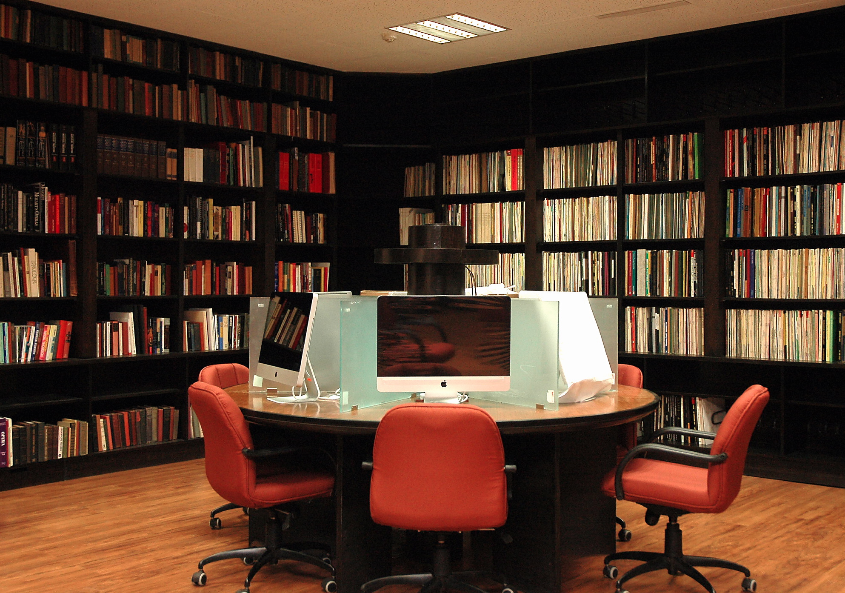

I am also an avid record collector. Not so avid as I was, but an avid record collector of old vocals. You make a lot of friends when you start having a hobby like this, both national and international. If you go upstairs and see our opera library, that came from a friendship with Vivian Liff and George Stuart. They had this absolutely wonderful library in London where I used to go to listen to records. And now that they are one floor above me, I have no time to go hear them.

NS: When did you work towards improving the performing arts scene in Bombay?

KS: I worked in the Tata Group for 32 years and knew Dr Bhabha quite well. I would often go have a chat with him about music. I once visited the National Centre for the Performing Arts on his request and suggested to him in 2001 to have a professional study made by IMG. They did make one and its still here. When I read it, I felt rather upset as there was so much to be done.

Afterwards I was was asked to help the NCPA. So I started coming here couple of times a week, then three times and soon after was appointed the Vice Chairman of this establishment. My corporate background was not able to accept the sort of organisation that was at the time prevalent. Gradually, I convinced TCS to come in and help us with management. We are still in the process and haven’t finished.

NS: How did you go about establishing the Symphony Orchestra of India?

KS: We met Marat Bisengaliev under strange circumstances. His chamber orchestra was the first one that came to Bombay. We first heard his orchestra at St. James’s Church in London and were quite amazed with the quality. So we went backstage and invited them. He didn’t believe that there was any music in India, so he came. And he’s been here ever since. Over time he visited twice or thrice with his orchestra and then one day suggested to try an All India Symphony Orchestra. He said to me that I went half mad reacting to that idea.

NS: That thought must have got you excited? What happened next?

KS: That got me excited a bit. And then Dr Bhabha, to whom I went with a little trepidation, to share this idea. He was as young a mind as you could imagine. Even at the age of 88, he asked if this would work. He didn’t say no. First he said, “Are you mad! Do you know what it entails?” I said I know what it entails and we had someone who could bring us a whole bunch of good musicians and play alongside a development course.

So we went through this huge process of auditioning. We called for musicians to Bombay and all we got out of Marat was a “Нет, Нет, Нет” (No, No, No!) for everybody.

NS: What plans do you have for the future of the Symphony Orchestra of India?

KS: We have a lot of plans but we must execute them properly. Now we have reached the stage where I think we can take on advanced work. When you can play the Bartok concerto for orchestra to a knowledgeable and sophisticated Swiss audience, with an applause and good reviews, then I think we are on the way. The only trouble is that we do not have enough Indians in the SOI. That saddens me. We are serious making an effort to put in as many Indians as possible. The trouble is that there is no training school or conservatoire in India for Western classical music. So where do the Indians come out from. We at the NCPA have started an advanced course of teaching string players. Among the resident musicians, there are about 12 foreigners.

They are very accomplished themselves and they teach and play here. We have about 34 pupils of a very good standard in this course and Marat feels that if they continue, some of them could play in the orchestra in three years time. Now that would be wonderful.

NS: How important is patronage? Do you think there should be more organisations such as the NCPA in every major city in India?

KS: Only if they know how to run it. There are so many institutions which exist, but are run terribly. There is no use starting something without the infrastructure and the content. The content is terribly difficult and one of the reasons why people fail is because they produce mediocre content. Mediocrity kills itself and slowly the audience dwindles away.

The reason why we are gradually getting full houses is because the quality of the SOI is now up to a very good standard. No doubt we can play internationally without any fear.

NS: What advice do you have for musicians that are not in Bombay and do not have access to the NCPA?

KS: Musicians who are good, particularly woodwind or brass, we could accommodate them easily if they reach a certain standard. Until I am here, and I hope after me also, I think the career of the SOI musicians is safe. I will try and choose a successor who will do the same. But I think it will happen. Once you establish a certain institution in a country, it doesn’t disappear. If it dies with me, then I am a bad manager. I have got to get it going for the organisation to sustain itself.

You can have a person driving it in the beginning and brining it to a certain standard. However it is upto the person to employ people who share and enhance his vision to carry forward the legacy. That should happen and I think it will go forward. My real ambition is to say that in India there is a career for a good professional musician.