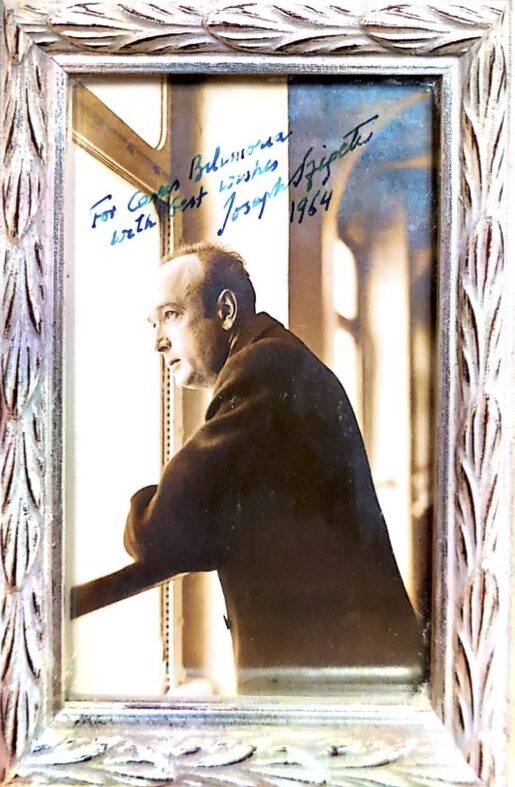

Joseph Szigeti: The Aristocrat Among Violinists

An exponent of the classical tradition and champion of contemporary music, the Hungarian-born musician’s oeuvre bears the stamp of his individuality and formidable technique. By Cavas Bilimoria

By the mid 1920s it seemed as if the zenith in bewitching sound, charm, elegance, suavity and virtuosity spearheaded by Ysaye and refined by Kreisler, Elman and Heifetz had been attained. Yet, there was a fascinating “outsider” who did not fit into this category and appealed to audiences that rejected the Kreisler-Elman-Heifetz criteria as the ultimate experience in violinistic art. This outsider was Joseph Szigeti, born in Budapest on September 5, 1892, in a small Carpathian town called Miramos-Sziget (hence the name Szigeti).

Born in a family of musicians, it was his uncle Bernat who started him on the violin at the age of seven. Sensing his great aptitude for the instrument, his father enrolled him in a private conservatoire under an unnamed teacher where he was taught the “Close to the body, book under the arm” method of bowing, an archaic and highly detrimental method vestiges of which remained throughout his career. But such was his innate genius that despite this mediocre training, when he auditioned for acceptance at the state music academy, Jenö Hubay, the Director, admitted him directly into his own class. Hubay, though purportedly a pupil of Joseph Joachim, had been powerfully influenced by the Belgian virtuoso Henri Vieuxtemps (Ysaye’s teacher) whom he revered. It was in this milieu of the Romantic Belgian school virtuosity that the young Szigeti’s musicality was formed.

Szigeti’s Berlin debut took place at the age of 13. The programme was:

Ernst: Violin Concerto in F sharp minor

Bach: “Chaconne” from Partita No. 2 and Prelude from Partita No. 3 for solo violin

Paganini: “Le Streghe” (The Witches’ Dance)

An arduous journey

In addition to this, his repertoire at that time was woefully limited and consisted of Wieniawski’s second Violin Concerto, Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, Viotti’s Concerto No. 22, Tartini’s Devil’s Trill Sonata and a few showpieces by Paganini, Sarasate, Hubay and Wieniawski. What the repertoire lacked while he was in Hubay’s class were concertos by Brahms and Bach, and sonatas by Beethoven, Mozart, Handel and Franck.

Szigeti was not destined for meteoric youthful fame as were Elman, Heifetz and Menuhin. His road to international renown was long and laborious. The lofty qualities in his playing that won him eminence in later years cannot be attributed to his teacher Hubay. The game changer was his contact and life-long friendship with Ferruccio Busoni, a superlative all-round musician. From that point on began his slow, arduous maturing process which in later years was to induce many observers to consider him “the greatest musician among violinists”. He now had the opportunity to hear and bask in the wondrous glow kindled by Ysaye, Kreisler, Elman, Busoni, and the conductors Arthur Nikish, Sir Hamilton Harty and Sir Henry Wood. Ysaye dedicated the first of the six sonatas he had composed for solo violin to Szigeti.

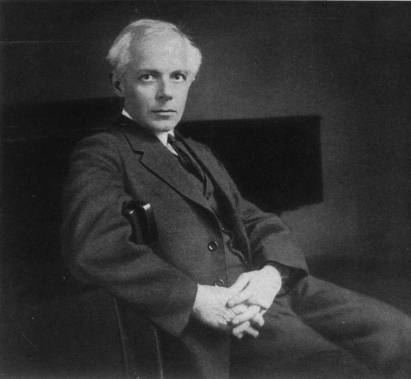

Szigeti knew who and what he was. He did not attempt to compete with Kreisler, Heifetz, Menuhin or Milstein on their home turf. His strength was that he was different, and a sizeable potential audience was waiting for just such a violinist to appear. He knew his strengths and weaknesses and concentrated on those masterworks of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms where he felt he could offer insights which were as individual as they were musically provocative. He also championed contemporary music. In his recitals he included Dvořák’s E minor and G minor Slavonic Dances (Kreisler arrangements), Kreisler originals, Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances (which he recorded with Bartók himself at the piano), his own difficult arrangement of Scriabin’s “Étude in Thirds” and Paganini’s ninth and twenty-fourth caprices.

Szigeti the violinist

His left-hand technique was formidable and comprehensive. His tone was soft-grained in texture and his vibrato, medium in speed. He did not produce an ear-titillating sound nor could he climax or conclude his runs with high voltage vibrancy. But in his prime he could negotiate the most awkward passages in the Brahms concerto with ease and precision and his intonation, always impeccable.

His bow arm, though schooled in that archaic way described earlier, drew a large and resonant tone. At times, his loud passages could be scratchy and his spiccatos, bowed very close to the bridge, were inclined to lose some clarity. But, as if to compensate for these shortcomings, he could produce delicate staccato passages and a variety of piquant, crisp bow strokes which added marvellous diversity in, for example, segments of the first movement of Beethoven’s concerto, much like Kreisler.

At no time did he sacrifice his own musical ideas to some strange philosophy of carrying out the composer’s intentions, but rather, created a wondrous fusion of the style, rhythmic pulse of the composer’s era and ethos with his own temperament and intelligence. He was a master of musical propulsion as well as genuine spiritual repose, not to be confused with the “repose” of some current artistes which consists of stopping their vibrato, playing with bone-dry barely audible sound, and rolling their eyes heavenwards as if in private communion with the deity.

Szigeti was one of the first classical violinists to join forces with a leading jazz musician. In a 1939 Carnegie Hall recital, he and Benny Goodman gave the premier of Bartók’s Contrasts for clarinet, violin and piano. It was later recorded with the composer at the piano.

Historically, Szigeti must be credited with exerting a powerful influence on the type of violin programmes prevalent today. As an artiste, he cannot be included among those who insist upon subjugation of one’s personality to the dictates of the so-called composer’s intentions. His art radiated his own humanism and no violinist ever played with more integrity.

Sample Recordings

This writer is fortunate to have a few of Szigeti’s recordings which deserve more recognition than what is given to them.

Prokofiev: Concerto No. 1 in D major (Beecham/London Philharmonic 1935)

Beethoven: Violin Concerto (Bruno Walter/British Symphony Orchestra 1932)

Beethoven: Complete violin/piano sonatas (with Claudio Arrau)

Mozart: Violin Concerto No.4 in D major, K218 (Beecham/London Philharmonic 1934)

Brahms: Violin Concerto (Sir Hamilton Harty/Halle Orchestra 1928)

Bloch: Violin Concerto in A minor, dedicated to and written for Szigeti

Handel: Sonata No. 4 in D major, Op.1 No. 13 (Nikita Magaloff pianist) 1937

Bach: Solo Violin Sonatas Nos. 1 and 3 (1931)

Bartók: Romanian Folk Dances (Bartok himself at the piano)

Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto (Beecham/London Philharmonic 1933)

Musical Intervention

In his illuminating blog published in September 2015, Zane Dalal, Associate Music Director of the Symphony Orchestra of India, put forward a hypothesis drawing fascinating numerical connections between Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra and his battle with leukaemia at the time of writing it. The blog came on the heels of the SOI’s performance of the work conducted by Dalal on 26th September 2015, Bartók’s 70th death anniversary. It also features the well-known story behind the concerto’s commission in which Szigeti had an instrumental role to play, written in Dalal’s inimitable style:

When placing a score on review in the months prior to a performance, one searches for the strength of the piece – that performers might derive that strength in playing and then transmit that strength to the listener. We owe the composer that process…that much at least! After the usual memory of great structural moments and caveats from previous performances had sunk into my processes, I began to search for more – taken forward by the story of the commission that everyone knows so well. In brief, Bartók had left for the United States in 1940, strongly opposed to the fascism that was sweeping through Europe. He had cancelled all engagements in Germany in protest of the Nazi regime and found his way to New York. He brought with him the beginnings of his struggle with cancer, which had started as a pain in the shoulder and remained misdiagnosed even after medical consultation. Bartók – the great pianist – could not find teaching assignments leave alone concert performances and by 1943 found himself in a hospital bed struggling with death – and almost certain to give way to illness or depression or both. If this had occurred, Bartók’s last piece would have been his sixth quartet written in Budapest in 1939, we would not have known his great concerto for orchestra, the third piano concerto or the relevant sketches for the great viola concerto. He would also have left less of a mark on the standard concert repertoire and it is entirely possible that I would not be writing this blog or offering remembrance as I did last night. At any rate, the great violinist Szigeti – with whom Bartók had collaborated on many occasions – joined in a pact with compatriot Fritz Reiner to save the moment as best they knew how. They approached Dr. Serge Koussevitsky – Music Director of the Boston Symphony – and asked if he might help, which he did, offering Bartók a cheque for one thousand dollars (c. $13,000/- inflation adjusted) at his hospital bedside to write a grand piece for orchestra. And so we have the Concerto for Orchestra.

The writer is indebted to Zane Dalal for his permission to republish excerpts from his blog, www.zanedalal.com/blog.

This piece was originally published by the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai, in the September 2021 issue of ON Stage – their monthly arts magazine.