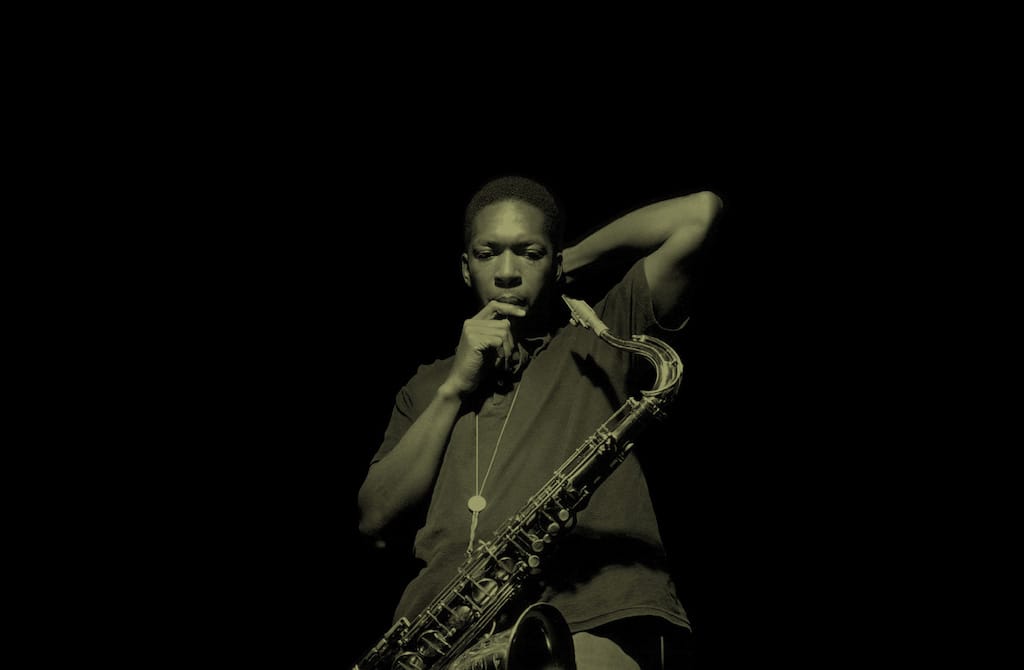

John Coltrane: From Bebop Virtuoso to Spiritual and Avant‑Garde Visionary

Spanning from bebop sideman to spiritual pioneer and free‑jazz trailblazer, John Coltrane’s musical odyssey transformed jazz. His modal innovations, devotional masterpieces like 'A Love Supreme' and fearless avant‑garde experiments continue to inspire listeners worldwide today.

John Coltrane’s name is synonymous with innovation, spiritual depth and technical mastery. Over the course of a relatively brief career, he transformed jazz, taking it from the hard‑driving complexities of bebop into a realm of profound introspection and boundary‑shattering experimentation. His journey, from sideman to bandleader, from bebop through modal and free jazz to deeply spiritual statements, remains one of the most compelling odysseys in twentieth‑century music.

Early Years and Bebop Foundations

Born in Hamlet, North Carolina, on 23 September 1926, John William Coltrane was raised in a musical family in a modest home near Philadelphia. His father was a tailor who played several instruments and his mother sang gospel in church; both instilled in him a love of melody and rhythm. After serving in the Navy during World War II, Coltrane enrolled at the Granoff School of Music in Philadelphia, where he studied theory and improvisation, absorbing the bebop vocabulary pioneered by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

Coltrane’s early professional life saw him playing in rhythm‑and‑blues and swing bands before joining Dizzy Gillespie’s big band in 1949. It was here that he began to forge his identity as a jazz improviser, though he was still finding his voice. His tenure with Gillespie was followed in the mid‑1950s by stints with Earl Bostic’s R&B ensemble and Johnny Hodges’s orchestra, all the while honing the rapid, intricate phrases that would characterise his later work.

The Miles Davis Quintet

In 1955, Coltrane’s fortunes altered dramatically when he joined Miles Davis’s group. Initially beset by personal struggles, including heroin addiction, he was famously “fired” by Davis in 1957 for his unreliability. But this setback catalysed a period of intense self‑discipline. Coltrane entered a rehabilitation programme and emerged determined to dedicate himself wholly to his craft.

Reinstated by Davis later that year, he became a central voice in the “first great quintet” alongside pianist Red Garland, bassist Paul Chambers and drummer Philly Joe Jones. Coltrane’s solos on landmark albums such as ’Round About Midnight (1957) and Milestones (1958) displayed his “sheets of sound” approach, cascades of rapid arpeggios and scales that overwhelmed the listener with their density and fervour. Yet beneath the virtuosity lay a yearning for deeper musical truth.

Modal Jazz and the Path towards Spirituality

The turning point arrived in 1959 with Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, often hailed as the greatest jazz album of all time. On tracks such as “So What” and “Blue in Green”, Davis and pianist Bill Evans introduced modal improvisation, a method privileging scales or “modes” over chord changes, which granted soloists more freedom. Coltrane’s extended lines, soaring and searching, hinted at his future spiritual quest.

By 1960, Coltrane had formed his own quintet, featuring McCoy Tyner on piano, Jimmy Garrison on bass and Elvin Jones on drums, initially accompanied by saxophonist Eric Dolphy. Albums from this period—Giant Steps (1960), Coltrane Jazz (1961) and My Favourite Things (1961)—demonstrated his continued technical bravura. The title track of My Favourite Things, a modal reimagining of a Rodgers and Hammerstein showtune, became a signature piece. Coltrane’s soprano‑saxophone melody, both haunting and ecstatic, hinted at his growing fascination with spiritual and non‑Western musical forms.

A Love Supreme

In December 1964, Coltrane entered Van Gelder Studio in New Jersey to record A Love Supreme, a four‑part suite comprising “Acknowledgement”, “Resolution”, “Pursuance” and “Psalm”. On this album, his quintet distilled years of musical exploration into a coherent, devotional statement. The music is suffused with gratitude, entreaty and exaltation; Coltrane chants in “Acknowledgement”, “A Love Supreme”, as his colleagues build a foundation of modal vamping and polyrhythmic propulsion beneath him.

A Love Supreme stands as a transcendent meeting of musical innovation and spiritual passion. It captures Coltrane’s belief in music as a vehicle for communion with the divine, a belief nourished by his growing interest in Hinduism, Buddhism and the writings of existential philosophers. The album’s influence has been immeasurable, inspiring generations of musicians to seek deeper purpose in their art.

Towards the Avant‑Garde: Breaking Every Rule

After A Love Supreme, Coltrane’s music grew ever more exploratory. His classic quartet—Coltrane, Tyner, Garrison and Jones—recorded formidable albums such as Crescent (1964) and Impressions (1963–65), balancing lyrical beauty with moments of intense free‑form interplay. Yet it was Coltrane’s own drive to push beyond established boundaries that led him to dissolve familiar structures altogether.

From 1965 onwards, he expanded his ensemble, adding percussionists and experimenting with double quartets, strings and unusual instrumentation. The landmark album Ascension (1966) featured a large ensemble engaged in collective improvisation, eschewing melody and harmony in favour of dense, orchestral eruptions. Critics and listeners were divided; some hailed it as a breakthrough in free jazz, others found it cacophonous. Coltrane himself described it as “an assertion of life’s constant renewal”.

His 1967 recordings for Impulse! Records, including Meditations and Expression, continued alongside recitals with Eric Dolphy’s widow, Charlotte, reflecting his uncompromising pursuit of new sonic territories. At the same time, his live concerts often stretched beyond two hours, culminating in climactic, exultant improvisations that swept audiences into ecstatic states.

Reception and Controversy

Coltrane’s later work provoked both admiration and controversy. Traditionalists accused him of abandoning melody and swing; avant‑garde enthusiasts revered his fearless abandon. In 1966, DownBeat magazine named him Jazz Artist of the Year, but his recordings of that era frequently baffled radio programmers and record buyers. Nevertheless, even detractors acknowledged the sincerity and intensity of his vision.

Musicians from across the jazz spectrum cited Coltrane as a pivotal influence. Saxophonists Pharoah Sanders and Sonny Rollins, pianists McCoy Tyner and Cecil Taylor, drummers Elvin Jones and Tony Williams—all felt his impact. Classical composers, too, found inspiration in Coltrane’s willingness to blur genre distinctions and to use music as a form of ritual.

A Legacy of Spiritual Resonance

Coltrane’s career was cut short by liver cancer, and he died on 17 July 1967. Yet his legacy endures, not only in the recorded catalogue but in the ethos he bequeathed to jazz and to art as a whole. His music invites listeners to engage not merely with technical prowess but with the profound questions of existence: of faith, of transformation and of communal transcendence.

In the decades since his death, A Love Supreme has been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame; in 2007, Rolling Stone placed him at number 17 on its list of “The 100 Greatest Artists of All Time”. His compositions—“Naima”, “Equinox”, “Giant Steps” and countless improvisations—remain staples of jazz repertoire worldwide.

Moreover, Coltrane’s spiritual message resonates across faiths and cultures. His integration of Eastern modes, African rhythms and devotional intensity prefigured later fusion experiments and the world‑music movement. Workshops, tribute bands and university courses continue to study his harmonic innovations, while his example encourages artists to view creativity as a form of sacred inquiry.

Why Coltrane Matters Today

In an age of digital distraction and commercial pressure, Coltrane’s music stands as a reminder of art’s potential to elevate the human spirit. His relentless curiosity, whether exploring the complex chord cycles of Giant Steps or the boundless freedom of Ascension, models a life devoted to growth. His turn to spirituality, marrying rigorous technique with heartfelt longing, points towards an art that transcends mere entertainment.

For modern musicians and listeners alike, Coltrane’s oeuvre offers multiple points of entry. One might begin with the approachable lyricism of My Favourite Things, progress to the meditative depths of A Love Supreme and finally confront the raw energy of his avant‑garde period. Each phase presents new challenges, new textures and new emotional landscapes.

John Coltrane’s journey from bebop sideman to spiritual and avant‑garde visionary reshaped the course of jazz. His technical innovations expanded the harmonic and rhythmic possibilities of the genre, while his spiritual quest infused his music with a transcendent power that continues to captivate and to heal.